My just-published story Trucks and Tanks, runner-up in JerryJazzMusician.com‘s 69th short fiction contest and written three months ago, is all too timely in Chicago, DC, Boston today. Trucks and tanks rolled down our leafy-treed, bungalow-lined street at dawn. I was already up, as usual, in my robe, t-shirt, sweaty sweats and slippers, mug of coffee […]

Listening to Coltrane’s “Ascension,” and what I’ve done. . .

Yesterday’s Concert dropped a podcast in which I offer guidance in listening even to challenging jazz recordings such as John Coltrane’s ambitious, gnarly Ascension. And semi-shameless self-promotion: Music Journalism Insider has published a comprehensive career interview with me. For Todd L. Burns’ invaluable, subscription-supported newsletter/platform about music journalism, I lay out at his request the […]

More on live jazz streaming, Chicago to Zurich and beyond

Saxophonist Chico Freeman, a third-generation Chicago jazzman, live-streams his new international band from Zurich on Saturday 2/27 at 2:30 pm ET, and I moderated their Zoom talk of coming together for the first time in person — a rarity over the past 10 months — with Carine Zuber, artistic director of Moods Digital, as part […]

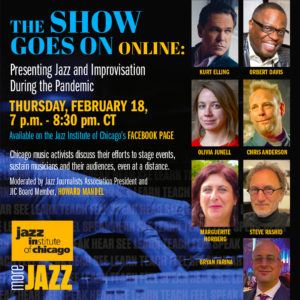

Jazz beats the virus online

Chicago presenters of jazz and new music, and journalists from Madrid to the Bay Area, vocalist Kurt Elling, trumpeter Orbert Davis and pianist Lafayette Gilchrist discussed how they’ve transcended coronavirus-restrictions on live performances with innovative methods to sustain their communities of musicians and listeners, as well as their own enterprises were in two Zoom panels […]

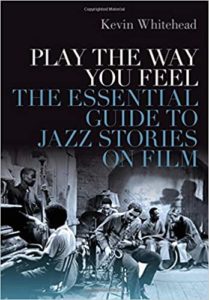

Love movies, jazz, and thinking about them? A treat

Movies, jazz and reading remain my favorite solitary diversions, and Fresh Air critic Kevin Whitehead enables immersion in all three with Play The Way You Feel: The Essential Guide to Jazz Stories on Film, his entertaining, provocative, deeply informed look at some 120 flicks and a handful of tv shows relating tales that mirror or […]

Four months of jazz adaptation, resilience, response to epidemic

In early March – only four months ago – I flew between two of the largest U.S. airports, O’Hare and JFK, to visit New York City. I stayed in an East Village apt. with my daughter and a nephew crashing on her couch. We ate barbecue at a well-attended Jazz Standard performance by drummer Dafnis […]

A dip into Mexico City street music and avant-garde

Here’s writing I worked hard on last year, published in slightly different form as a “Global Ear” column in The Wire (UK) December 2019. Rafael Arriaga’s photos (unless credited otherwise) are a fit complement, as is Jazzamoart’s painting, “El Bop de los Alebrijes.” The Harmonipan players, khaki-uniformed men and women grinding away for spare change […]

Guitarist Kenny Burrell shouldn’t be in trouble. But he is.

Guitarist Kenny Burrell — since the 1950s a prominent, popular and influential jazz innovator, recording ace, bandleader and esteemed educator (prof and director of Jazz Studies at UCLA) — at age 87 is suffering grievous financial calamity due to health care costs and multiple frauds. His plight is candidly detailed by his wife Katherine at […]

Audio-video jazz improv: Mn’Jam Experiment, w/teens

What’s really new in improvisational music? Where else can innovation go? Mn’JAM Experiment — singer Melissa Oliveira and her visual/electronics/turntablist partner JAM — are daring to mix high-tech audio-with-video media in live performance, and as they say, it’s an experiment, in a direction that live performance seems sure to go. Grounded in jazz fundamentals (call […]

Extraordinary Popular Delusions, Chicago free improv all-stars

Keyboardist and synthesizer specialist Jim Baker has led the collective quartet Extraordinary Popular Delusions playing every Monday night in obscure Chicago venues for the past 13 years. My article on EPD, which features saxophonists Mars Williams and Edward Wilkerson Jr. (they switch off), multi-instrumentalist (bass, guitar, trumpet) Brian Sandstrom and percussionist/drummer Steve Hunt — all […]

Luminous PoKempner pix of Sun Ra’s celestial music

Marshall Allen, ageless 94, leads the Sun Ra Arkestra If you liked Black Panther, listen to the music that introduced and embodies Afro-Futurism. Photojournalist Marc PoKempner captured a bit of the celestial magic of the Sun Ra Arkestra (est. circa 1954) during its November touchdown in New Orleans’s Music Box Village. This picturesque venue is […]

Chicago blues at 90

Guitarist Jimmy Johnson’s birthday at Space – photos by Harvey Tillis  Blues have been heard in Chicago for about 100 years — and blues guitarist Jimmy Johnson has been alive for 90 of them. Johnson, born just four years after Papa Charlie Jackson was reported busking with his guitar on Maxwell Street, celebrated his entry […]

Jazz and beyond projects with 2018 NEA funding support

Given all the noise, the National Endowment for the Arts’ $25 mil for arts, literature and education announced Feb. 7 may have been overlooked. But these funds and the projects they support, nationwide, should be noted. From more than $3 million going to initiatives strictly labeled “Music” (exclusive of “Musical Theater” or “Opera”) here’s my subjective selection of […]