I’m not funny, and wish I were. Witty, yes, sometimes, and I’m pretty good at making an audience laugh when lecturing (a situation in which the prevailing standards are admittedly fairly low). But plain old drop-dead funny? Absolutely not. The only time I ever brought down a house was when I contrived to be hit in the face with a cream pie in front of an audience of pubescent classmates who thought they were going to be forced to listen to me give a prize-winning speech as part of a talent contest. That stopped the show. Short of such skullduggery, though, I lacked the power to impose my personality on a crowd, and still do. As a naughty but honest colleague said of Leopold Godowsky, a legendary turn-of-the-century pianist who was miraculous in the studio but dull in the concert hall, my aura extends for about five feet. This incapacity has made it hard for me to be funny and impossible for me to be either an actor or a conductor, two professions toward which I was briefly drawn when I was young and foolish….

Read the whole thing here.

This is Louis Armstrong’s one hundred and thirteenth birthday, and he remains as central to American life and culture today as he was when he died in 1971.

This is Louis Armstrong’s one hundred and thirteenth birthday, and he remains as central to American life and culture today as he was when he died in 1971.

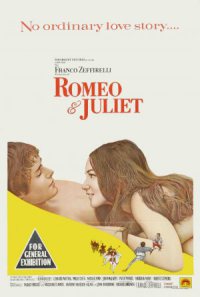

I first became aware of Shakespeare through Franco Zeffirelli’s

I first became aware of Shakespeare through Franco Zeffirelli’s  As I

As I

Mr. Bond, in the manner of most modern British playwrights, is a man of the left, and “The Sea,” which dates from the dawning of the Age of Thatcher, can be read as a portrait of class warfare among the provincials. But like Shaw and Bertolt Brecht, his masters, Mr. Bond is too much the artist to content himself with coarse ideological parallels. Instead he turns his imagination loose, and the result is a midnight-black comedy that whipsaws the viewer between uproarious small-town satire and a stoicism so bleak and astringent (“The years go very quickly and you seem to be spared the minutes”) that it makes your skin tingle.

Mr. Bond, in the manner of most modern British playwrights, is a man of the left, and “The Sea,” which dates from the dawning of the Age of Thatcher, can be read as a portrait of class warfare among the provincials. But like Shaw and Bertolt Brecht, his masters, Mr. Bond is too much the artist to content himself with coarse ideological parallels. Instead he turns his imagination loose, and the result is a midnight-black comedy that whipsaws the viewer between uproarious small-town satire and a stoicism so bleak and astringent (“The years go very quickly and you seem to be spared the minutes”) that it makes your skin tingle. And how does it do so today? Last week PBS announced its new Arts Fall Festival lineup. Paula Kerger, the network’s president and CEO, has been playing it ultra-safe ever since, in 2011, she launched the Fall Festival, PBS’ flagship arts-programming venture. I surveyed the first year’s shows and found them to be “a stiff dose of the usual safety-first pledge-week fare.” I hoped back then that things might improve over time, but the entries for 2014 are even blander and more predictable….

And how does it do so today? Last week PBS announced its new Arts Fall Festival lineup. Paula Kerger, the network’s president and CEO, has been playing it ultra-safe ever since, in 2011, she launched the Fall Festival, PBS’ flagship arts-programming venture. I surveyed the first year’s shows and found them to be “a stiff dose of the usual safety-first pledge-week fare.” I hoped back then that things might improve over time, but the entries for 2014 are even blander and more predictable….