In today’s Wall Street Journal I review a new play off Broadway, Stephen Adly Guirgis’ Between Riverside and Crazy, and a revival in the Berkshires, Noël Coward’s Design for Living. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Stephen McKinley Henderson is an actor’s actor, universally admired in the business but mostly unknown outside it. Why? Because he’s a character actor, not a leading-man type. He plays supporting roles, some of them quite small, though you never fail to notice him. A case in point was the recent Broadway revival of “A Raisin in the Sun,” in which he was onstage for no more than five minutes yet still managed, as the saying goes, to eat everybody else’s lunch. That makes it all the more delightful to watch him strut his formidable stuff in Stephen Adly Guirgis’ “Between Riverside and Crazy,” of which he is, at long last, the undisputed star. Mr. Henderson, who spends most of the play sitting in a wheelchair, acts with such seeming effortlessness that you’ll have to look twice—maybe even three times—to catch him stealing every scene.

Stephen McKinley Henderson is an actor’s actor, universally admired in the business but mostly unknown outside it. Why? Because he’s a character actor, not a leading-man type. He plays supporting roles, some of them quite small, though you never fail to notice him. A case in point was the recent Broadway revival of “A Raisin in the Sun,” in which he was onstage for no more than five minutes yet still managed, as the saying goes, to eat everybody else’s lunch. That makes it all the more delightful to watch him strut his formidable stuff in Stephen Adly Guirgis’ “Between Riverside and Crazy,” of which he is, at long last, the undisputed star. Mr. Henderson, who spends most of the play sitting in a wheelchair, acts with such seeming effortlessness that you’ll have to look twice—maybe even three times—to catch him stealing every scene.

They’re worth stealing, too. Like “The Motherf**ker with the Hat,” Mr. Guirgis’ last play, “Between Riverside and Crazy” is a hard-headed kitchen-sink comedy, one that has serious things to say about lower-middle-class urban life, race relations and the corrosive effects of resentment on the human soul. Yet the playwright makes his points in an unfailingly unpredictable way, embedding them in the twisty tale of a retired, newly widowed cop (Mr. Henderson) who got shot off duty and is well on the way to wasting the rest of his life fuming about it….

“Design for Living,” Noël Coward’s fizzy 1933 comedy about two men in love with a woman who can’t choose between them, is the least frequently performed of his major plays, for two obvious reasons. The denouement, in which the three lovers accept their fate and form a ménage à trois, is so self-evident an apologia for Coward’s own unorthodox private life that he actually permits himself to get obtrusively preachy in the third act: “We have our own decencies. We have our own ethics.” Moreover, “Design for Living” calls for three sets and a budget-bending cast of 10. The last time I saw it staged, by the Shakespeare Theatre Company of Washington, D.C., it was done very expensively—and very, very well. But few regional theater companies are capable of mounting so elaborate a production these days, so “Design for Living,” fine though it is, typically gets overlooked by cheese-paring artistic directors.

Now for the good news: Tom Story, one of the stars of the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s 2009 production, has directed a stylish revival of “Design for Living” in the Berkshire Theatre Group’s 122-seat Unicorn Theatre. The scale is intimate, the décor modest but attractive, and the three leads are played by Chris Geary, Tom Pecinka and Ariana Venturi, three talented graduate students from the Yale School of Drama who turn Otto, Leo and Gilda into a trio of bright but unsure young things who play at life in order to find themselves. It’s an engagingly fresh take…

Now for the good news: Tom Story, one of the stars of the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s 2009 production, has directed a stylish revival of “Design for Living” in the Berkshire Theatre Group’s 122-seat Unicorn Theatre. The scale is intimate, the décor modest but attractive, and the three leads are played by Chris Geary, Tom Pecinka and Ariana Venturi, three talented graduate students from the Yale School of Drama who turn Otto, Leo and Gilda into a trio of bright but unsure young things who play at life in order to find themselves. It’s an engagingly fresh take…

* * *

To read my review of Between Riverside and Crazy, go here.

To read my review of Design for Living, go here.

•

•  The last time I lived in a house was 1974. The house in question was the one in which I grew up, in which my mother lived from 1961 until her death three years ago, and in which my brother and sister-in-law now live. Since then I’ve wandered from city to city, apartment to apartment, and hotel to hotel, and the word “home,” which used to mean 713 Hickory Drive, Smalltown, U.S.A., now means…what? Wherever Mrs. T happens to be, I suppose, but it’s also true that there are

The last time I lived in a house was 1974. The house in question was the one in which I grew up, in which my mother lived from 1961 until her death three years ago, and in which my brother and sister-in-law now live. Since then I’ve wandered from city to city, apartment to apartment, and hotel to hotel, and the word “home,” which used to mean 713 Hickory Drive, Smalltown, U.S.A., now means…what? Wherever Mrs. T happens to be, I suppose, but it’s also true that there are  On Monday I returned to Lenox to spend a few days seeing shows, and I wondered how it would feel to be there after so long an absence. The answer, to my surprise, is that it felt like coming home. The mountains were as beautiful as ever, the restaurants as fine, the traffic as exasperating. (The only way to get anywhere fast in the Berkshires is to hop a ride on a fire engine.) The next night I drove over to Shakespeare & Company’s Tina Packer Playhouse, the theater where Satchmo at the Waldorf was performed, to see a new production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that was set in New Orleans in the Twenties. Tony Simotes, the director, said in his program note that he’d been inspired by Satchmo. It all felt as familiar as a well-worn pair of slippers…and yet it wasn’t. For I was no longer part of the company, as I had been in 2012: I was, once again, a visitor.

On Monday I returned to Lenox to spend a few days seeing shows, and I wondered how it would feel to be there after so long an absence. The answer, to my surprise, is that it felt like coming home. The mountains were as beautiful as ever, the restaurants as fine, the traffic as exasperating. (The only way to get anywhere fast in the Berkshires is to hop a ride on a fire engine.) The next night I drove over to Shakespeare & Company’s Tina Packer Playhouse, the theater where Satchmo at the Waldorf was performed, to see a new production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that was set in New Orleans in the Twenties. Tony Simotes, the director, said in his program note that he’d been inspired by Satchmo. It all felt as familiar as a well-worn pair of slippers…and yet it wasn’t. For I was no longer part of the company, as I had been in 2012: I was, once again, a visitor.  When the off-Broadway transfer of Satchmo closed at the end of June, I was perforce mustered out of the Society of People Putting on a Show. Only temporarily, I hope, but for the moment I am, as theater people say, a civilian. And as I sat in the Packer Playhouse on Tuesday night, I found myself thinking of the last lines of a different Shakespeare play, Love’s Labour’s Lost, in which Adriano de Armado draws a bright line between the separate lives of actors and audience: The words of Mercury are harsh after the songs of Apollo. You that way: we this way.

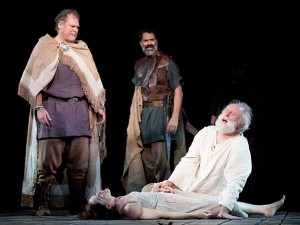

When the off-Broadway transfer of Satchmo closed at the end of June, I was perforce mustered out of the Society of People Putting on a Show. Only temporarily, I hope, but for the moment I am, as theater people say, a civilian. And as I sat in the Packer Playhouse on Tuesday night, I found myself thinking of the last lines of a different Shakespeare play, Love’s Labour’s Lost, in which Adriano de Armado draws a bright line between the separate lives of actors and audience: The words of Mercury are harsh after the songs of Apollo. You that way: we this way. Primary among those objections is that save for being unusually tall, Mr. Lithgow is as unregal as an actor can be. He is the quintessential comic WASP, at once haughty and absurd, and he is unfailingly effective in plays in which such folk are brought low, like David Henry Hwang’s “M. Butterfly” or David Auburn’s “The Columnist.” But while “Lear” has its moments of black comedy, its anti-hero is nonetheless heroic: He is pitiful, not preposterous.

Primary among those objections is that save for being unusually tall, Mr. Lithgow is as unregal as an actor can be. He is the quintessential comic WASP, at once haughty and absurd, and he is unfailingly effective in plays in which such folk are brought low, like David Henry Hwang’s “M. Butterfly” or David Auburn’s “The Columnist.” But while “Lear” has its moments of black comedy, its anti-hero is nonetheless heroic: He is pitiful, not preposterous.