I try not to drop foreign words or phrases into my writing (in fact, I told a member of my criticism class yesterday to remove C’est vrai and Gesamtkunstwerk from the piece of his that I was editing). Once in a while, though, there’s no good alternative, and schadenfreude is one of those rare exceptions to my personal rule. To derive malicious joy from someone else’s troubles is, if I may be so bold as to say it, precisely the sort of concept for which one would expect the Germans to have coined a word, and it seems to me altogether fitting that we should have taken it over without change….

Read the whole thing here.

• A cyberfriend writes to remind me that when Charles Dickens visited America for the first time in 1842, he was mobbed wherever he went, an experience that he described in a letter to John Forster, his friend and biographer:

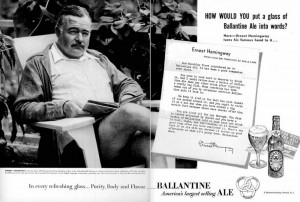

• A cyberfriend writes to remind me that when Charles Dickens visited America for the first time in 1842, he was mobbed wherever he went, an experience that he described in a letter to John Forster, his friend and biographer: I suppose a modern-day reader might regard this as a nice problem to have, but what strikes me most forcibly about Dickens’ dilemma (if you want to call it that) is that it was a novelist who was having it. Today it’s unimaginable that any writer would be treated that way, whether in America or elsewhere. Our “rock stars” are…well, rock stars. Or, more likely, movie and TV stars. We simply don’t confer mass celebrity on writers nowadays. If I had to guess, I’d say that Ernest Hemingway was the last novelist of consequence whom a considerable number of Americans would have been at all likely to know by sight—he was, in fact, famous enough to be paid to endorse products—and he died more than a half-century ago.

I suppose a modern-day reader might regard this as a nice problem to have, but what strikes me most forcibly about Dickens’ dilemma (if you want to call it that) is that it was a novelist who was having it. Today it’s unimaginable that any writer would be treated that way, whether in America or elsewhere. Our “rock stars” are…well, rock stars. Or, more likely, movie and TV stars. We simply don’t confer mass celebrity on writers nowadays. If I had to guess, I’d say that Ernest Hemingway was the last novelist of consequence whom a considerable number of Americans would have been at all likely to know by sight—he was, in fact, famous enough to be paid to endorse products—and he died more than a half-century ago.

I grieve to report the passing today of my friend D.G. Myers, a critic of great force and penetration who also

I grieve to report the passing today of my friend D.G. Myers, a critic of great force and penetration who also  Mr. Yando is well known to Chicago playgoers for his fearlessly forthright acting in Writers’ Theatre’s “Dance of Death” and the Court Theatre’s “Angels in America.” Even for him, though, this is a career-clinching performance, noteworthy not just for its unflagging intensity (he is fully as potent in the first half of the play as he is after intermission) but also for its textured complexity. Great violence alternates unpredictably with great tenderness in Mr. Yando’s Lear. At once frightened and frightening, he lashes out with startling physicality at his family and followers to cloak the slow crumbling of his consciousness, making all the more terrible the question that he asks of his Fool: “Who is it that can tell me who I am?”

Mr. Yando is well known to Chicago playgoers for his fearlessly forthright acting in Writers’ Theatre’s “Dance of Death” and the Court Theatre’s “Angels in America.” Even for him, though, this is a career-clinching performance, noteworthy not just for its unflagging intensity (he is fully as potent in the first half of the play as he is after intermission) but also for its textured complexity. Great violence alternates unpredictably with great tenderness in Mr. Yando’s Lear. At once frightened and frightening, he lashes out with startling physicality at his family and followers to cloak the slow crumbling of his consciousness, making all the more terrible the question that he asks of his Fool: “Who is it that can tell me who I am?” In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I discuss the critical and political contretemps stirred up by the opening of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new David H. Koch Plaza. Here’s an excerpt.

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I discuss the critical and political contretemps stirred up by the opening of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new David H. Koch Plaza. Here’s an excerpt.