main: October 2008 Archives

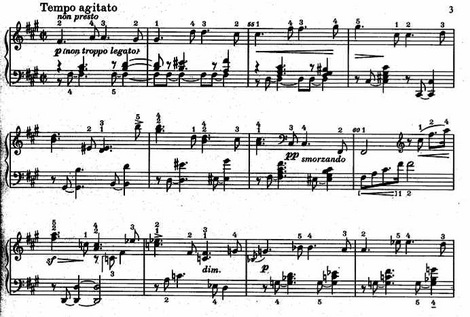

Anyway, back to Grand Hotel. It's a huge, sprawling, 37-minute essay, one of those complex pianistic virtuoso marathons mostly notated on three if not four staves, played in a frantic fury by Gerard Bouwhuis, and based on Beethoven's Op. 111 Sonata. The opening diminished-seventh chords of that piece burst forth frequently, and many of the streams of falling 32nd-notes come from the concluding scale passages of Beethoven's first movement. The longer (naturally) second movement is dotted with less obvious references to Beethoven's tranquil Arioso theme, often simply sudden secondary dominant chords that hang quietly in the air. Key signatures - three flats, six sharps, five flats - run through the piece, although it more often sounds atonal than diatonic. The title, according to the liner notes, is a reference to the crumbling edifice of tonality, which certainly stands nobly, but in ruins, here. I'm told by one of his students that Cornelis de Bondt (b. 1953) teaches theory at the Hague Conservatory. I'll upload an mp3 here for you, as is my wont, but only temporarily, for it's a big file and I can't spare the space forever.

Grand Hotel is a interesting contrast to Clarence Barlow's Variazioni e un pianoforte meccanico, which is a theme and variations for live pianist and Disklavier based on the theme of Op. 111's second movement. Barlow's achievement is a stunning logical and technological feat, the computer grabbing data from Beethoven's theme and composing its own cheery, sometimes almost humorous variations. Grand Hotel is far darker and more introspective, a kind of existential, manic-depressive drama featuring Op. 111's elements in dozens of flashbacks, playing with sudden recognitions and buried shards of memory.

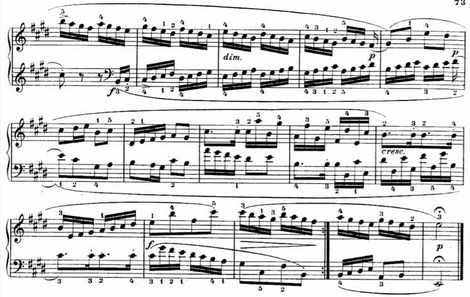

As documented here, though 95% of my musical influences are American, I've got my own long history of associations with Op. 111, a piece which haunts me almost as much as the Hammerklavier haunted Brahms. (Other European pieces deep in my compositional bloodstream include Mahler's Sixth - which turned up in Custer and Sitting Bull - the adagio of Bruckner's Eighth, Busoni's Fantasia Contrappuntistica, Boulez's Rituel, and everything Erik Satie wrote.) I've never directly quoted Op. 111 except in my Disklavier piece Petty Larceny, which consists entirely of quotations from the Beethoven sonatas, but my I'itoi Variations of 1985 was a kind of spiritual homage to it, and my two-movement piano concerto Sunken City mimicked Op. 111's proportions and movement contrasts. In grad school, for Peter Gena's class on the late Beethoven sonatas, I wrote a paper titled "Zen and Op. 111," in which I analyzed the piece as a contrast between samsara and satori, between the earthly veil of illusions and the tranquility of Zen consciousness. My idea was that the first movement's angry diminished sevenths chords represented a relentless drive to the final, sad resolution, while the arioso variations gradually defuse the polarity between tonic and dominant, creating an image of timelessness in which resolution becomes unnecessary:

(Years later, in a review of Pauline Oliveros, I described this same C-D-F-G sonority as a musical equivalent of the Yin-Yang symbol, a union of tonic and dominant with no thirds to specify major or minor.)

Obsessively quoting every historical thinker from Basho to Nietzsche and beyond, "Zen and Op. 111" was too embarrassingly immature to make public now, but at the time I was moved to write it by a book that I recently had the tremendous pleasure of rereading: R.H. Blyth's Zen in English Literature. This is one of the books Cage read in the '40s, and one I had discovered through his writings. Blyth was a British Japanese scholar who sat out World War II in Japan, and whose books on haiku elevated that genre to heightened visibility in the West. Zen in English Literature is an absolutely charming tome, a virtuoso display of astonishing erudition (which I tried ineffectively to imitate) in which he traces examples of Zen consciousness through Wordsworth, Dickens, Shakespeare, Keats, Blake, Pope, Donne, Milton, Chaucer, Cervantes (not English, but included anyway), and many others. Hamlet's "There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so" is the book's continually recurring mantra, and he finds Zen in every perfectly self-forgetful artwork: "Art is frozen Zen." No isolated example will do the book's flavor justice, but for instance Blyth compares George Herbert's

I made a posie, while the day ran by:

Here I will smell my remnant out, and tie

My life within this band,

But time did beckon to the flowers, and they

By noon most cunningly did steal away

And wither'd in my hand.

with Basho:

Leaves of the willow tree fall:

The master and I stand listening

To the sound of the bell.

as a type of self-identification with nature. Zen is Blyth's poetic criterion, in fact, and for want of it he damns Coleridge as merely a sentimental pantheist.

Zen in English Literature is the liveliest and most enlightening introduction to Zen for a Westerner I've ever found; it's long out of print, but I located a used copy from Amazon, and enjoyed it all over again. By Blyth's way of thinking, Zen could be found in much (or any) great music, but there's something special about the second movement of Op. 111 and its gradual dissolution of 19th-century goal-directed syntax. In fact, one could impose the two movements of Op. 111 as a metaphor on modernism versus minimalism, or perhaps postclassical music, in general: anxiety, portentousness, climax-orientation, and ambition versus calm, intuition, flatness, and paradoxical nonsequitur. The karma-riddled first movement is entirely classical, but the Arioso lays out a postclassical harmonic agenda many decades before the fact. Perhaps that's why the piece has never relaxed its hold on me, and every musical work that makes reference to it demands my attention.

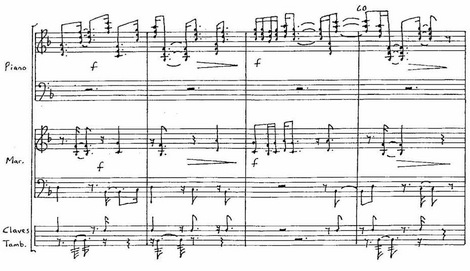

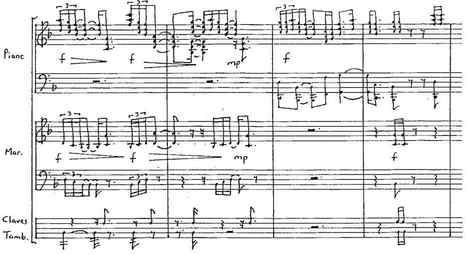

Patterns of Plants is a series of compositions based on the melodic patterns that are extracted from the data of slight changes of electric potential found in living plants. Such a procedure was made possible by "Plantron," an apparatus conceived by bio-media artist Yuji Dogane... The compositional process... starts from finding out "musical values" in the changes of electric potential. By finding out "musical value," I mean an attitude to regard the changes as "voices of plants" and to gather melodic patterns while listening to their voices.

Here's the thing about Americans. You can send their kids off by the thousands to get their balls blown off in foreign lands for no reason at all, saddle them with billions in debt year after congressional year while they spend their winters cheerfully watching game shows and football, pull the rug out from under their mortgages, and leave them living off their credit cards and their Wal-Mart salaries while you move their jobs to China and Bangalore.

And none of it matters, so long as you remember a few months before Election Day to offer them a two-bit caricature culled from some cutting-room-floor episode of Roseanne as part of your presidential ticket. And if she's a good enough likeness of a loudmouthed Middle American archetype, as Sarah Palin is, John Q. Public will drop his giant-size bag of Doritos in gratitude, wipe the Sizzlin' Picante dust from his lips and rush to the booth to vote for her. Not because it makes sense, or because it has a chance of improving his life or anyone else's, but simply because it appeals to the low-humming narcissism that substitutes for his personality, because the image on TV reminds him of the mean, brainless slob he sees in the mirror every morning.

And again:

We're used to seeing such blatant cultural caricaturing in our politicians. But Sarah Palin is something new. She's all caricature. As the candidate of a party whose positions on individual issues are poll losers almost across the board, her shtick is not even designed to sell a line of policies. It's just designed to sell her.

And as a public service announcement, some much-needed publicity for the Alaska Secessionist Movement.

I met Schuman once. He had some piece played in Chicago in 1986, and I reviewed him by phone for the Chicago Reader, then introduced myself at the performance. I wish I had had the chutzpah to insist on getting to know him. I told him that at home, beneath my bed, was a box of compositions I wrote in high school, most of them attempts to plagiarize the bleak opening atmosphere of his Eighth Symphony. In perfect crusty-old-sea-captain character he growled, "Surely you can do better than that!" Here's the passage in question, a reiterating series of succulently grim major-minor triads leading to a long, angularly wandering horn solo:

I know it's fuzzy, but try to look at those two harps and the piano, with tubular bells playing both thirds of the triad and a grace-note in the glockenspiel. Delicious. There are few passages in the orchestral literature I love so dearly. It's desolate, haunted, almost motionless, yet palpably not despairing; there's a latent energy to the rhythm and even the subtly shifting voice-leading that somehow forecasts the sardonic fireworks that will come in the third movement. It's as Americanly tragic (sorry, "tragically American" just won't do) as The Grapes of Wrath - a novel that coming events may compel us all to reread. I love Schuman's Third, Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Symphonies too, and his New England Triptych, and I played his less impressive piano piece Voyage which had a little impact on my piano writing, but the Eighth is the one I kept trying to duplicate.

My guilty secret is that before I discovered Cage at 15, I had already lost my creative vriginity to the Harris Third, the Schuman Eighth, and the Bernstein Second (gang-banged, as it were). My high school composing style slithered around among Schuman, Harris, Ruggles, Copland, Bernstein, and - more consciously but a little more distantly as well - Ives. Had I not then fallen in with the Cage crowd, I suppose I'd be writing symphonies today. And I still suspect that my personal take on minimalism, heard through glacially moving microtones, minor-triad obsessions, and even my fetish for the 11/9 interval (347 cents) that's halfway between major and minor, was conditioned by the spellbinding effect Schuman's gloomy chords had on me at a tender age.

I'll put up a first-movement mp3 here temporarily, but hopefully everyone already knows this piece.

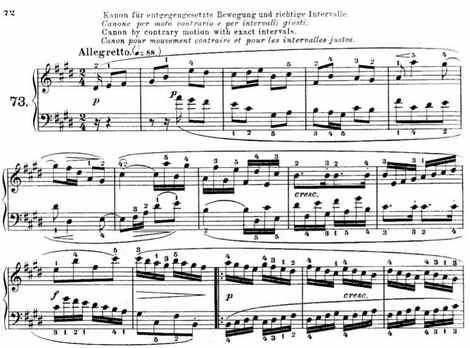

You can hear the canon here in a recording by Danièle Laval. Of course in E major he has to reflect the lower voice around F#, because the major scale (as a glance at the keyboard will show, noting D's position among the white keys) is symmetrical around the second scale degree. Debussy tweaked fun at Gradus ad Parnassum in his Children's Corner, and Charles Rosen blasts the collection as a marathon of mechanical soullessness. He's almost 100 percent wrong. They're all teaching pieces on some level, but included are dozens of lovely, memorable vignettes, variously diverging toward early Romantic harmony and warm neo-Baroque counterpoint.

I've always gotten a kick out of keeping a secondary musicological specialty besides contemporary American music, sort of as a hobby and to keep new music in perspective. My period used to be medieval, which I studied in grad school with Theodore Karp, one of the leading figures in the field. But the last time I taught medieval, the textbook (by Jeremy Yudkin, the only enjoyably readable medieval music text) contradicted half of what I said, and I realized that that field changes too fast for me to keep track of - pieces are now attributed to different composers than was true when I was in grad school, and even the technical terminology has changed. So several years ago I switched to Classical Era as a secondary specialty, though I only do the instrumental music; most 18th-century opera bores me to tears. I enjoy taking students through the Haydn symphonies because they're so incredibly varied and numerous, though it's a rare student who shares my enthusiasm for Haydn. And I try to show them that the period was a lot funkier than it gets credit for, by playing Albrechtsberger's concertos for jew's harp, Michele Corrette's Combat Naval with its forearm clusters on the harpsichord, and music in odd meters like this fugue in 5/8 by Beethoven's childhood friend Antonin Reicha:

But I bring up Clementi's inversion canon even in composition lessons as an example of grace achieved under intense compositional restrictions.

is varied to become the second theme (and later inverted to become the closing theme):

It imparts to Clementi's sonatas a lovely brand of introversion you don't find in Mozart or Beethoven, a sense of the theme-hero being inflected according to its changing role in the sonata structure, and the whole movement being narrowly focused. I point this out to demonstrate how this particular sonata exhibits one of the cleverest strategies in leading to the recapitulation I've ever found. The development ends up on the dominant of A minor, and a modified form of the main theme emerges, moving ambiguously between e minor and G major, and finally reaching a dominant on G just in time for the second theme:

That means that, thematically, the piece arrives at the recapitulation thirteen measures before it reaches it tonally (i.e., a return to the tonic key), and uses the recapitulation of the main theme as its transitional element modulating back into the tonic. It's an elegant structural pun, the theme serving to embody, hint at, and retransition to the recap all at once. Very smooth, very clever. Clementi clearly spent a lot of time thinking about the potential subtleties in sonata form and how to play around with them. There are many similar examples in his music (and Op. 37 No. 2 pales next to the six magnificent sonatas of his Op. 40 and Op. 50). And when you compare this level of structural thought and compositional rhetoric to the kind of awkward, slapdash transition that Mozart could jerry-rig in a now-famous sonata even as late as K. 545:

it's clear that some of the excess idolatry we lavish on Mozart could aptly be retooled as honest admiration for Clementi, and for Jan Ladislav Dussek as well. Not that Clementi ever wrote anything that could match Mozart's late piano concerti and operas (though he did provide Mozart with a theme for the Magic Flute overture), but it's kind of silly and sad, given our far more complete view of the 19th century (except for the remarkable Franz Berwald) that we impart such a cartoonish, one-dimensional view of the classical era, just Haydn-Mozart-Beethoven with Gluck occasionally thrown in. Beethoven grew up with Clementi's sonatas and borrowed from them, and I sometimes wonder what Ludwig thought of poor Clementi, a well-respected composer 19 years his senior, reduced to becoming Beethoven's publisher and representative of his piano retailer. In my Evolution of the Sonata class, I try to correct the balance.

In Westminster Abbey a few years ago, I ran across Clementi's grave by accident. (The English adopted him as they did Handel.) It was a thrill to run into someone whose music has given me so much pleasure.

Sites To See

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog