foot in mouth: June 2009 Archives

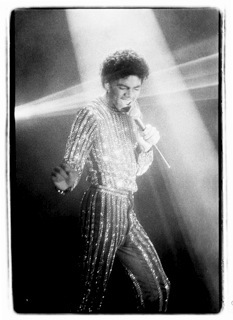

A friend called Thursday night, and I was slow to pick up. When we finally caught each other, he quipped, "Yeah, I know, you've been busy mourning Michael Jackson." But I'd been mourning him for years.

A young Michael Jackson (by Kate Simon, via the New Yorker)

Every time I saw a photo of Jackson more bleached, more narrow-nosed, more hidden behind glasses and scarves, than ever, I felt incredibly sad, and also implicated--part of a culture that devours its artist-celebrities whenever the glossy shell of celebrity they need for protection doesn't suit them. Jackson didn't want to be devoured, so he offered up a more and more dubious likeness of himself.

To New York Times editorial writer Verlyn Klinkenborg's excellent point that Jackson's "was a music we wanted to visualize, to see formalized and set loose in dance," I want to add that the singer did some of the best visualizing himself. He changed the ground beneath him and the air around him when he danced. He could skate along the floor without hardly lifting his feet and, in the aptly named Moon Walk, he concentrated all of his virtuosity on getting his feet on the ground rather than off, like he really was on the moon. (And maybe he really was.)

In a thoughtful tribute to his dancing, Times critic Alastair Macaulay compares Jackson with a whole bunch of performers, but doesn't mention the ones I'm most reminded of: Charlie Chaplin and the legendary tappers the Nicholas Brothers. Here's Chaplin singing opera--sliding backward thickly like a matador and stepping jauntily like Jackson likes to do, too (the Chaplin clip has been hard to pick because it's not a particular move but flickers of resemblance I'm struck by), and here are the tuxedoed Nicholas Brothers sliding and jumping over their own legs and changing direction on a dime in Down Argentine Way from the '40s and then, 30 years later, doing the disco thing with none other than Michael and the Jackson Five, letting the pelvis carry the feet:

Though the tone is entirely different--Jackson isn't a comic like Chaplin, and Motown and disco intervened between his kind of debonair and the Nicholas Brothers'--these lithe men also could travel while still standing on their feet, because they also were strong in the middle and light at the periphery. Jackson is their hyperbole.

His funky musicality helps with the magical exaggerations. He moves on the downbeat, which makes the transitional steps slide by as in a flipbook, where they fall between the sheets.

Here Jackson is in a 1983 Motown celebration and here he is doing the moonwalk, and here he is, in the trippy video for "Don't Stop Till You Get Enough," being his charming young-man self (I love the leg waggles, the turned out feet, the laid back torso, the easy, swinging pelvis--the whole loose gangly thing. And, yeah, I know, these aren't the moves that revolutionized--made a feat out of--pop-star dancing, but he does do them like no one else: looser, easier, and more shy.)

For other possible influences, here is a fantastic Youtube montage

of everyone from Bill "Bo Jangles" Robinson to Eleanor Powell, Earl

"Snakehips" Tucker, Tip, Tap, and Toe, and a whole host of other 20th

century luminaries I should have heard of. (But not Jimmy Slyde--he

should be in here somewhere).

My friend, Foot contributor Paul Parish, who, a couple of years ago when we were talking about who could be our ambassador, our Pavarotti, of dance, was quick to offer Michael Jackson, writes this morning (Monday) to say:

The thing is, Jackson's dancing really translates into video -- it's pure terre-a-terre dancing, no loft to it at all, and the tiny changes he'll make in his profile register with alarming clarity on the two-dimensional screen. I agree with Alastair, it's so premeditated I kinda hate it; it's so determinedly cool, everything that's NOT cool has been edited out, and at some level I devoutly believe that's what killed him. I thought he was going to die in his last show -- it frightened me, he looked like he could not breathe. I was not surprised to hear that he'd died. The first thought that went through my head when I turned on the radio and heard it was, "Of course."

My friend Brian Seibert, critic and tap historian, writes this afternoon (Monday):

Chaplin and The Nicholas Brothers as precursors for MJ? Certainly. Jackson was a sponge, a sampler, a great appropriator. And as your twin examples demonstrate, he had no prejudice about the sources he stole from. That's obvious in his earliest recordings, the kid who can so amazingly mimic his elders, suggesting adult emotions through adult style. (Young Harold Nicholas was like that, too, channeling Cab Calloway instead of James Brown.) But Jackson was just as precocious in his physicality. Forget Man in the Mirror; the man was a mirror. And his precocity, his magpie mimicry, was daring. "The Origins of the Moonwalk," the illuminating YouTube compilation you mention, leaves out his most immediate models: the Godfather of Soul and the lesser-known Jackie Wilson and all of the Motown groups Young Michael grew up among, all doing the steps of the tap-dancer-turned-choreographer Cholly Atkins. Yet the compilation suggests the deep tradition behind Jackson -- the moonwalk was older even than that 1940s clip of Bill Bailey -- and includes Sammy Davis, Jr., a precocious black hoofer who first made it big by doing impressions of white celebrities. The impressions were so dead-on that they were mocking, which frightened Sammy's older stage partners, his father and his "uncle." But Sammy wasn't going to accept any artificial limit on his influences, his talent, or his audience. Jackson took it a few leaps further, and he paid a similar price: the usual pressures of child stardom and extreme celebrity, but also a chameleon's uncertainty about who he really was. After Bad, the influences that resonated through Jackson's dancing narrowed, or they became less about dancing and more about spectacle (for instance, the odd, fascist aesthetics of History). I suppose the protests-too-much crotch-grabbing was an attempt to stay current, but by that point, he was beyond imitating others. He could only imitate himself. And so as his appearance morphed horribly, his style stayed fixed; now he resembled his imitators, the way that Sammy Davis came to resemble Billy Crystal's version.

This week's New Yorker piece by Kelefa Sanneh about how much of "Wanna Be Startin' Somethin'" came from Manu Dibango raises questions about how much Jackson stole and how much he added, questions that are even more equivocal when it comes to dance and dance's more fluid and weaker notions of copyright. What isn't equivocal is how Jackson inspired a passion for dance in millions.

He was my entry. It was that famous "Billie Jean" performance at the Motown 25th. He moonwalked a white, middle-class nine-year-old in suburban LA into acquiring a miniature Beat It jacket, the spangled socks, the single, sequined glove. More important, he moved me to learn the choreography to all of his videos. I made my father film me re-creating them. As anyone who's seen me dance at a wedding can confirm, I still remember those moves, and everyone in my generation recognizes them immediately. It was decades after I learned them that I learned to recognize where they came from. That took some research. But Michael was the introduction, as he was for so much of the world.

That clip of Jackson with The Nicholas Brothers, by the way, doesn't show any of them to advantage. As moving as it is for the Jacksons to invite the brothers onto their variety show--an outlet that the Nicholases never had, and Sammy had only briefly--that routine finds the entertainers meeting in the shallowest part of showman's versatility, the Vegas they shared. That they shared deeper things is abundantly clear in their better, more sui generis performances, also wonderfully available on our new library of dance, Youtube. Who's being inspired, online, right now? -- Brian

I respond:

Brian, Thank you. I wish I could get my hands on that video of you doing your Michael impersonations.

I agree, the Nicholas Brothers' meet-up with the Jackson Five doesn't show them to advantage--readers, click on this link to Down Argentine Way for that--but I didn't even know Michael could tap; I liked watching him do it.

Being older than you--how much? a decade?--I don't associate Jackson with being cool, but with getting to be a young child for a bit longer: how great that even when you were in third grade and reading chapter books, you could still sing about the ABCs and 1-2-3s! (I was six when the ABC album was released, but don't remember hearing the song for another couple of years.) Yeah, I associate Michael Jackson with childhood, and I think he did, too, growing up in reverse, to catastrophic effect. (Maybe those recent movies about men starting at age 70 and working backwards--Youth against Youth and Benjamin Button--were inspired by him.) By junior high, I'd "graduated" from the Jackson Five to Earth, Wind, and Fire, the Commodores, and Tower of Power, and by college everyone was doing the Robot and the Moonwalk, and I didn't know where those moves had come from, they were that viral, but guessed it had something to do with the boys spinning on cardboard on their heads on the street. Wrong again. My chronology was--as it is--full of holes of inattention.

I too hope someone's being inspired now.

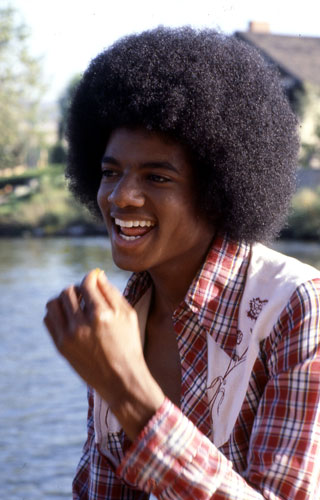

A beautiful Jackson at 20, in 1978, smiling, not dancing.

Diana Vishneva approaches her roles with a completeness of imagination that makes the usual day-after review--this worked, that didn't--feel especially meager.

For example, in Swan Lake most ballerinas identify the swan queen Odette's creaturely gestures with her fear, her guardedness, her vulnerability--the feelings that Prince Siegfried's everlasting love promises to defuse. But last night at the Met, Vishneva made clear that her swan gestures--extraordinarily expansive and sinuous--would no more disappear than the years of sorrow imprinted on her character. The prince (here a game Marcelo Gomes) has arrived too late. Odette can only receive his love, not reciprocate it, and she can only receive it like a queen--through the shield of her station.

During the long, iconic pas de deux by the lake where Siegfried finds Odette, Vishneva doesn't look at him, or at least she doesn't see him. She looks inward and moves through a deep sorrow in one long exhalation of steps ribboned with creaturely impulse. This Odette is not sharing a story; Siegfried is simply overhearing one. She wants someone's help, someone to pledge his love, the way a pidgeon wants bread crumbs. Siegfried could be anyone.

Vishneva reveals how a woman losing personhood acquires wildness and queenliness in equal measure. Vishneva has taken what we normally think of as opposite ends of a spectrum--on one end, the ritual formality of a queen, on the other, instinct--and bent them into a circle. In her, hopelessness, queenly reserve, and animal otherworldliness merge.

Her interpretation may not make for great theater--it renders Siegfried nearly superfluous--but it yields great poetry and great insight, perhaps more even than Swan Lake can bear.

The American Ballet Theatre summer season continues this week with "Swan Lake," next week with Frederick Ashton's "Sylvia" (Vishneva debuts in the title role) and its final week with Kenneth MacMillan's "Romeo and Juliet" (which the ballerina has performed several times now, always incredibly). Also, ABT has just announced its short fall season, at Avery Fisher Hall this year: all new works, by Aszure Barton, Benjamin Millepied, and Ratmansky. Neat!

[Postscript below this photo:]

Marcelo Gomes and Diana Vishneva in Swan Lake.Photo for ABT by Gene Schiavone.

On a more mundane note, whoever is designing--or executing-- the lighting for Swan Lake (not to mention all sorts of other ballets at the Met this season) should be tutored in the basics. Last night, it wasn't just a matter of lousy conception, though that was a problem, too. (Examples: Overuse of side lighting and underuse of the overheads, so you couldn't see the dancers' faces; only one spot for the two leads, so when they weren't in each other's arms you could only see one of them at a time; the front of the stage bathed in gloom even when that's where the action was). It was also a matter of absurdly amateurish execution: the spot dawdling behind its object, half the swan corps sunk in shade so they seemed smaller in number than they were, etc. Afterward, my friend Elaine wanted to know, "Why shouldn't the prince prefer the black swan? She was much more fun." But Elaine couldn't really see the white swan!

Also--I hate this sort of commentary, as it feels like a violation of the dancer's privacy, but as it bears on aesthetic issues, I'll risk it--La Vishneva has gotten so skinny, her white swan tutu hanging on her frame, that it's starting to have artistic consequences. In multiple pique turns, her arms wobble in their roundedness, probably from upper-arm weakness (I've noticed this in other very thin dancers, and not in anyone else). And such thinness puts incredible pressure on a dancer's technique. It's the Gelsey Kirkland effect, where as long as the dancer has achieved a perfect calculus of balanced limbs, her weightlessness works. But otherwise, she has no extra muscle to get through small deviations from perfection. I could understand how a maniac like Vishneva might like the extra challenge, but in the long haul I'm not sure it's good for her dancing or herself.

I'll write again when I can, about some of the dances I've seen in the last few weeks (including a revisit to Ratmansky's On the Dnieper, where it seemed even better).

Dear Reader,

In order not to tempt me to write posts, when I have other, less tempting things to do, I am declaring a hiatus here for the next few weeks.

But to not leave you completely high and dry, here are the dances in New York I would go see (and likely will go see) in these last weeks of the heavy dance season before the dog days (and the Lincoln Center Festival) set in.

For modern and postmodern dance, I am looking forward to:

* Sarah Michelson's Dover Beach at the Kitchen next week, June 9, Tuesday through Saturday. (This will likely sell out--so get your tickets soon.) Here's a profile I wrote on the always surprising choreographer at her last New York premiere, Dogs at BAM. And--this just in--here's her fantastically interesting interview with Time Out editor and Times writer Gia Kourlas. (To get Michelson to talk about advanced work is a feat, so this is a real treat.)

* Pam Tanowitz's debut at Dance Theater Workshop with likely another compellingly mysterious work (in a quirky Cunningham vein) Thursday June 18 through the 20. (DTW has a short video here which conveys the style if not the lusciousness.)

* What looks like an interesting variation on the shared-evening rubric by Ben Munisteri and Rebecca Stenn, June 11 through 14, at Joyce SoHo. The press release says,

Munisteri and Stenn remix the other's choreography.... Their rules: Each choreographer creates a 10-minute dance. Then the other choreographer (who is not allowed to add any new movement vocabulary) recomposes the original material to render something entirely new (the way a DJ would create a remix).

* Kate Weare at Danspace Project in the East Village June 25 through 27. Weare combines sly wit, emotional fierceness, and vulnerability.

* At the Joyce, Philadanco, with a New York premiere by hip-hop postmodernist Rennie Harris, June 16 through 21; and Larry Keigwin and Nicholas Leichter alternating days June 23 through 28. Keigwin can be too cute, but this piece, to Ravel's heavy Bolero was given a "wow!" by my esteemed colleague Roslyn Sulcas at the Times. The musically astute Leichter tends to set club-dance vocab within a modern dance structure--and he's bold about his musical choices. He served as choreographer for the Brooklyn Philharmonic's Rite of Spring and this time is doing a dance to Stevie Wonder--how can you lose? Here's a clip. (Confidential to Eva: the next best thing to a musical--or maybe better, eh?)

Nicholas Leichter Dance in Free the Angels. Photo by Tom Caravaglia.

And now for ballet:

This week, Russian choreographer Alexei Ratmansky makes his much-awaited debut as resident choreographer at American Ballet Theatre with On the Dnieper, part of a Prokofiev triple bill that also includes Balanchine's wrenching Prodigal Son.

Veronika Part (green), Paloma Herrera (white), and Marcelo Gomes in Ratmansky's On the Dnieper. Photo by Fabrizio Ferri for ABT.

This debut has been so anticipated, given the light Ratmansky brought to the future of New York City Ballet with two premieres there, that he can hardly equal our hopes. Best probably to go with no expectations. Ratmansky is very smart and, even better, very wise, and if at first he doesn't succeed, he will later. [UPDATE Monday late night: He succeeded. See the * at the very bottom of this post for more on this valiant night.]

Next week at ABT is Giselle, which if you haven't seen, you must, even if you don't normally go in for story ballets. Dance is at the heart of the story, about a peasant maiden whose joy is dancing, and for whom dancing--and loving--is too dangerous to survive. I have brought willful friends who deliberately limit their ballet diet to plotless Balanchine and they were won over. (Here's my review of Nina Ananiashvili and Angel Corella last year. Scroll down a bit. And here's a short review of Diana Vishneva in the role.) I recommend the Russians: Ananiashvili in her last season at ABT, Kirov-ABT ballerina Diana Vishneva, and young Bolshoi sensation Natalia Osipova, in her first season with the company.

From June 15 through the 20th ABT offers another Romantic ballet, La Sylphide, on a double bill with Paul Taylor's Airs, another welcome addition. How nice to see La Sylphide directly after Giselle. I've never seen ABT's version, so it's hard to say who would be best as the Sylph. I'm most curious about Hee Seo, because it's such a big role for a corps member, with David Hallberg, who has won me over finally and completely. (I know, I've been slow.) For Veronika Part fans, La Sylphide offers several outings. I'm going to sit her out for this role. I'm not confident that she can be sylphic-- mischievous and light. All Part's mystery rests with sadness and majesty. She's an introverted dancer, almost a contradiction in terms. But I will come out for her Swan Lake, which, people tell me, is her best role. She's performing it on Friday June 26, near the end of a week of Swan Lakes.

ABT finishes out its season--in July, so I'll be brief, as I wanted to confine myself to this month--with Ashton's alternately wondrous and very funny Sylvia (she's the Greek nymph you've never heard of), for which Gillian Murphy, the mistress of comedy, is perfectly suited and which Vishneva is dancing for the first time. (Vishneva's first Ashton, a couple of years ago, was his Midsummer Night's Dream, in which she interpreted "fairy queen" so literally and so imaginatively as to make you lean forward in your seat in wonder: in her love dance with Oberon, she dangled and wafted her limbs like a dandelion blown and lost to the wind.) The final offering is MacMillan's Romeo and Juliet, with Murphy and Hallberg debuting. (The ballet will be interesting to see after the plain but not naturalistic so much as natural--when it felt like it--Mark Morris version. I am in the minority: I loved the Morris. I wonder what its adamantly plainspoken magic will do to the MacMillan for me).

I should have written already about New York City Ballet, whose spring season always begins a couple of weeks before ABT's.

I am too late to recommend that you see the Benjamin Millepied premiere, in which he takes a great leap forward as a choreographer. He's developed a whole language, and it's not, as some critics have suggested (because they stop looking when they think they spy Eurotrash), the usual post-Forsythian spasm fest. It's more eloquent, more varied, at once more creaturely and more distilled. What's most awful about the push-and-pull of Forsythe imitators is its rhythmic predictability --which confirms the choreographers are on autopilot--while Millepied's rhythms, to an eerily compelling Gorecki score, are a prism of subtle shifts in feeling and tone. I hope the dance will return this winter.

It's also too late to catch the captivating Robert Fairchild channeling Baryshnikov's dreamer (Baryshnikov originated the role) in Robbins's Opus 19/The Dreamer. His performance doesn't feel like an imitation, it feels like a possession, that's how complete, and uncanny, the transformation is. The impetus of his dream is Janie Taylor at her waifish, mercurial best--flung about by inner impulse one moment and moving with crisp precision the next. Taylor is one of the few ballerinas who loses neither herself nor the role to the idiosyncrasies of both. It's such a rare, essential, paradoxical gift. Here's more, by my esteemed colleague Tonya Plank aka Swan Lake Samba Girl on the miracle of Fairchild and Taylor together.

You can catch each of them separately this week: Fairchild in Balanchine's spiky romance, Stravinsky Violin Concerto, and Taylor (along with Jennie Somogyi! and Wendy Whelan!) in Balanchine's lushly romantic parlor dance, Liesbeslieder Walzer (which a few of us discussed a couple of years ago here and here).

It's also not too late to catch Balanchine's Art-Decoish distillation of Swan Lake, where Wendy Whelan, with her modernist intelligence, is his perfect Odette. You have one more day, Saturday June 6 matinee. It may not come back next year, as this is its second go. Sebastien Marcovicci is her noble prince, elongated and buoyant after a rather squashed Chaconne this winter.

Next week, we get a chance to see an early Christopher Wheeldon ballet, Mercurial Manoeuvres, which he made even before the company created the post of resident choreographer for him.

The NYCB season ends with the perfect final ballet: Balanchine's magical Midsummer Night's Dream. The casting isn't up yet, but it has many great roles, so it's hard to go wrong.

Oberon (Joaquin De Luz), Titania (Maria Kowroski), and Bottom in Balanchine's A Midsummer Night's Dream. Photo by Paul Kolnik for the NYCB.

I'm sure I've forgotten something crucial--and will likely end up adding it here.

Otherwise, have a lovely first month of summer.

~Apollinaire

*Short PS on ABT's Prokofiev triple bill, which includes, besides the Ratmansky premiere and Prodigal Son, the company premiere of Desir by longtime National Ballet of Canada choreographer James "Cinderella" Kudelka:

By the end of the night, I'd dubbed the program The Impossible Dances--impossible either because of the contrary demands of score and libretto (On the Dnieper), of modes and moods (Prodigal), or of steps and their intent (Desir). Given these conditions, everyone performed admirably.

Prodigal mixes a sardonic sense of humor with straight-out pathos, and Constructivist Expressionism (yeah, that's my term) with naturalism. But all the Sons I've seen (Joan Boada at SF Ballet, and at NYCB Daniel Ubricht and no less than Peter Boal and Damian Woetzel, all in the last decade) have tilted the ballet toward comedy, with the boy's masklike open-mouthed shouts of rebellion and pounding of fists on thighs demonstrating his foolishness, not a stylized--a Primitivist--form of acting. ABT dancers have a better shot at the role because they're used to stylized acting (for them, it's usually 19th century mime).

Herman Cornejo was the best Prodigal Son I've seen, though he still has a ways to go. (For example, during the crawl back home, he needs to fall from his knees to his belly not like an athlete such as himself--with a rubbery rebound--but like a man so weary and worn, he cannot even rise to his feet.) Cornejo had the rash arrogance of a young tom: the cat does crazy things not out of habit but from thoughtless instinct and excess energy. He is not bad so much as callow.

ABT often takes a season to settle into recently acquired Balanchines, but already some details are brighter here than at New York City Ballet, such as when the regiment of goons bombard the Son with so many hands to shake, in syncopated rhythm, that he manages to grasp nary a one; or when the father forces the Son to bow in prayer with his sisters, and the boy sneaks his head up early (he knows his family won't catch him out, as their pious heads will still be bowed).

With Desir, Kudelka is after a pronounced awkwardness. I admire his ambition to have the seams of the partnering--where often the aim is to be as smooth as possible--show, so instead of the pas de deux signifying the usual rapturous love, it suggests something more strenuous, more conscious, more worked on.

The problem is, the steps are so demanding and at such high speed that the awkwardness often looks inadvertent. The dancers did absolutely everything they could to make the stiff-legged moves look deliberate--part of a continuum from herky-jerky to smooth. Now Kudelka needs to do something so the dance can be equal to its idea. So many of the patterns are fantastic; it would be worth simplifying or slowing things down to bring out their meaning or at least their details. (Gillian Murphy was alone in fully registering the dance's contrariness, but she's always exceptional at mastering two dynamics at once, such as a noodling torso and steely legs.)

Finally, On the Dnieper (I know, you've been waiting): I thought Ratmansky did the best he could--which at times was a great deal--with a story that was too emotionally complex for a short ballet (it's 40 minutes) and with music--winsome, striking music-- that seemed to work against the story it was supposed to tell.

The story involves a soldier (Marcelo Gomes) who comes home to find the sweetheart he left behind (Veronika Part) still devoted to him. But he is in the mood for love--which means new love. When Paloma Herrera bounces into view, he wants her. And gets her--after the man to whom her parents have betrothed her (David Hallberg) beats him to a pulp. Herrera and Gomes run off, and Part is left crumpled and alone.

The ending is really affecting--abandonment always is--as is the opening scene where the soldier (Gomes) has come home to cherry blossoms in bloom and is overwhelmed with a placeless desire that spins his head (and his body, of course, this being ballet). But in between there just isn't enough time to establish the characters. For example, what's the attraction of this bouncy new girl? (Maybe it's just that she mirrors the soldier's own jagged energy: Herrera's steps were very good at conveying not an ideal but a real woman--edgy and wanting always to be the center of attention.) And, other than being the soldier's lover, who is this woman who has waited for him, and what was he to her that she would wait? Part is quivery with disappointment and abjection even before she has been rejected--and maybe that's the point. It doesn't matter who he is, she will always want him because she knows she will always lose him.

Still, the men are clearer: Hallberg's character comes to the fore when he realizes his bride feels trapped. He endures paroxysms of emptiness and confusion. It's a fantastic dance. Gomes establishes his character's desire for novelty and his overwhelmedness right away, with antsy, swift shifts in direction that melt into a big sigh of happiness at the beauty and relief of being home. He sinks into the earth and looks up through the cherry blossoms to the night sky.

As the poster Michael points out on a Ballet Talk forum, the group (family, friends, villagers) is essential to the dance--and Ratmansky's ways of showing the various kinds of force they exert on the lovers (snooping, ignoring, castigating) is ingenious. But the groups here still aren't as clearly etched as in Russian Seasons or Concerto DSCH, both for New York City Ballet.

Ratmansky might have been better off doing a plotless ballet, freeing himself of the burden of story to establish cause and effect.

That said, On the Dnieper was never boring. The movement was delightful and surprising: lots of petit allegro (I wish the feet had been better lit) with the arms and torso moving in large arcs and long yet staccato lines. The feet seemed to move twice as fast as the body: actions are quick, feelings take time.

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Recent Comments