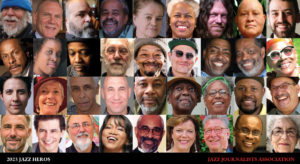

Since 2001, the Jazz Journalists Association (over which I preside) has celebrated some 350 “activists, advocates, altruists, aiders and abettors of jazz,” as Jazz Heroes. The class of 2024 Jazz Heroes has just been announced, recognizing the good works of 33 people whose efforts extend from the Baja-San Diego borderland to Ottawa, Canada, through 27 […]

Who plays the saxophone? And why?

I love the sound of a saxophone, or rather the broad range of sounds available from this family of reeds instruments. Breathy, vocal-like, smooth, light, penetrating, gritty or greasy, able to cry and/or croon (sometimes both at once), it strikes me as capable of the most personal of musical statements, although that’s probably a projection […]

Appreciating Charnett Moffett as a solo bassist

Saddened that bassist Charnett Moffett has died of a heart attack at age 54, I post this appreciation — also serving as a profile — written in 2013 to annotate his solo bass (!) album The Bridge, which he described as “my most personal and challenging release so far.” Solo bass records are rare, and […]

Happy 90th to electronic music pioneer Herb Deutsch

Herb Deutsch, the trumpeter-pianist-Theremin player-composer-Moog synthesizer co-creator and jazz inspired improviser turns 90 today, February 9, 2022, and a hearty Happy Birthday to him! In celebration, Moog Music has produced a video interview with this emeritus professor of Hofstra University, where he taught composition and electronic music, as the first of a series titled Giants. […]

Jazz Autumn: Returns, galas and even awards

If all “jazz” shares a single trait, it’s that nothing will stifle it. Adjusting to covid-19 strictures, Chicago (just for instance) in the past two months has been site of: A stellar Hyde Park Jazz Festival; Herbie Hancock’s homecoming concert at Symphony Center; audiences happily (for the most part – no reported incidents otherwise) observing […]

City of Chicago, music promoter

Lollapalooza 2021 had some 385,000 attendees (without significant Covid-19 outbreak, fortunately) but featured little of host Chicago’s indigenous talent or styles. And that’s just wrong, declared Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events commissioner Mark Kelly, launching the month-long Chicago in Tune “festival” at a reception August 19. Here’s the still-evolving event calendar of hundreds […]

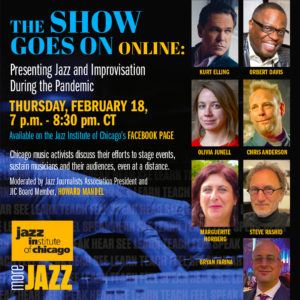

Jazz beats the virus online

Chicago presenters of jazz and new music, and journalists from Madrid to the Bay Area, vocalist Kurt Elling, trumpeter Orbert Davis and pianist Lafayette Gilchrist discussed how they’ve transcended coronavirus-restrictions on live performances with innovative methods to sustain their communities of musicians and listeners, as well as their own enterprises were in two Zoom panels […]

Boogie-man Helfer bounces back from covid-depression

Erwin Helfer, the 84-year-young Chicago pianist of heartfelt blues, boogie, rootsy American swing and utterly personal compositions, has told his tale of covid-19-related profound depression, hospitalization, treatment and recovery to the Chicago Sun Times. I’m a longtime friend, ardent fan and two-time record producer of Erwin’s, and had lunch with him soon after the article […]

RIP Annie Ross: Her last stand with Jon Hendricks

Annie Ross, who died July 21 at age 89, sold “Loch Lomond” as a seven-year- old in the Little Rascals with brass equal to her hero in “Farmers Market” hawking beans. The child of Scottish vaudevillians, she was maybe never shy. In 2002 I reported on her last stand with fellow vocalese icon Jon Hendricks, […]

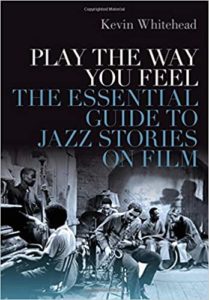

Love movies, jazz, and thinking about them? A treat

Movies, jazz and reading remain my favorite solitary diversions, and Fresh Air critic Kevin Whitehead enables immersion in all three with Play The Way You Feel: The Essential Guide to Jazz Stories on Film, his entertaining, provocative, deeply informed look at some 120 flicks and a handful of tv shows relating tales that mirror or […]

Four months of jazz adaptation, resilience, response to epidemic

In early March – only four months ago – I flew between two of the largest U.S. airports, O’Hare and JFK, to visit New York City. I stayed in an East Village apt. with my daughter and a nephew crashing on her couch. We ate barbecue at a well-attended Jazz Standard performance by drummer Dafnis […]

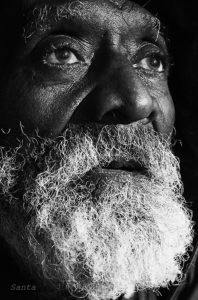

Revered jazz elders, deceased: portraits by Sánta István Csaba

As a generation of jazz elders leaves our world — some hastened by the pandemic — their faces as photographed by Sánta István Csaba become even more luminous, haunting, iconic. Originally from Transylvania and currently living in Turin, the northern Italian area with heaviest covid-19 infections, Sánta reports that he is healthy, employed at the […]

Future Jazz past: Hal Willner, circa 1992

The death of funny, smart, idiosyncratic, unique music producer Hal Willner at age 64 saddens me. We were East Village neighbors in the go-go ’90s, flush with ideas to try in the future. Here’s my entry about him from Future Jazz (Oxford U Press, 1999). CONCEPT PRODUCER AS VISIONARY “My projects happen mostly by accident,” […]