Yesterday’s Concert dropped a podcast in which I offer guidance in listening even to challenging jazz recordings such as John Coltrane’s ambitious, gnarly Ascension. And semi-shameless self-promotion: Music Journalism Insider has published a comprehensive career interview with me. For Todd L. Burns’ invaluable, subscription-supported newsletter/platform about music journalism, I lay out at his request the […]

Appreciating Charnett Moffett as a solo bassist

Saddened that bassist Charnett Moffett has died of a heart attack at age 54, I post this appreciation — also serving as a profile — written in 2013 to annotate his solo bass (!) album The Bridge, which he described as “my most personal and challenging release so far.” Solo bass records are rare, and […]

Happy 90th to electronic music pioneer Herb Deutsch

Herb Deutsch, the trumpeter-pianist-Theremin player-composer-Moog synthesizer co-creator and jazz inspired improviser turns 90 today, February 9, 2022, and a hearty Happy Birthday to him! In celebration, Moog Music has produced a video interview with this emeritus professor of Hofstra University, where he taught composition and electronic music, as the first of a series titled Giants. […]

Holidays with music, in person or not

Despite my avowed abhorrence of Christmas music, I enjoyed maestro Kurt Elling leading his hometown quintet in a holiday-themed performance at Chicago’s City Winery last Sunday. My entire evening — accompanied by best friends, and including the surprise discovery after the Winery show of a heartening young trumpeter at the Hungry Brain — was a […]

Jazz Autumn: Returns, galas and even awards

If all “jazz” shares a single trait, it’s that nothing will stifle it. Adjusting to covid-19 strictures, Chicago (just for instance) in the past two months has been site of: A stellar Hyde Park Jazz Festival; Herbie Hancock’s homecoming concert at Symphony Center; audiences happily (for the most part – no reported incidents otherwise) observing […]

In praise of Donald Newlove

I was knocked out on first reading of Sweet Adversity (1978), by Donald Newlove, who died Aug. 17 at age 93. It’s about co-joined twins who love Louis Armstrong, play jazz in the 1930s and arrive New York’s Lower East Side in the early 1960s, where one of them sobers up. Besides the unique story, […]

City of Chicago, music promoter

Lollapalooza 2021 had some 385,000 attendees (without significant Covid-19 outbreak, fortunately) but featured little of host Chicago’s indigenous talent or styles. And that’s just wrong, declared Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events commissioner Mark Kelly, launching the month-long Chicago in Tune “festival” at a reception August 19. Here’s the still-evolving event calendar of hundreds […]

Tania Leon interview 1989

Tania Leon, 2021 winner of the Pulitzer Prize for music composition, has not often been interviewed in the popular press, so here’s a Q&A I conducted with her as published in 1989 by Ear magazine, and Jeremy Robins’ 2007 Composers Portrait of her, commissioned by American Composers Orchestra. Tania Leon, Assistant conductor of the Brooklyn […]

Record man Koester’s blues and jazz legacy

Chicagoan Bob Koester, proprietor of the Jazz Record Mart and Delmark Records for nearly 70 years, is a model of music activism and entrepreneurship from an era rapidly receding and unlikely in current business circumstances. Neil Genzlinger did a nice formal New York Times obit, and I’ve written a remembrance for the Chicago Reader. Although […]

More on live jazz streaming, Chicago to Zurich and beyond

Saxophonist Chico Freeman, a third-generation Chicago jazzman, live-streams his new international band from Zurich on Saturday 2/27 at 2:30 pm ET, and I moderated their Zoom talk of coming together for the first time in person — a rarity over the past 10 months — with Carine Zuber, artistic director of Moods Digital, as part […]

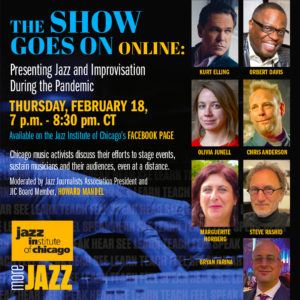

Jazz beats the virus online

Chicago presenters of jazz and new music, and journalists from Madrid to the Bay Area, vocalist Kurt Elling, trumpeter Orbert Davis and pianist Lafayette Gilchrist discussed how they’ve transcended coronavirus-restrictions on live performances with innovative methods to sustain their communities of musicians and listeners, as well as their own enterprises were in two Zoom panels […]

Boogie-man Helfer bounces back from covid-depression

Erwin Helfer, the 84-year-young Chicago pianist of heartfelt blues, boogie, rootsy American swing and utterly personal compositions, has told his tale of covid-19-related profound depression, hospitalization, treatment and recovery to the Chicago Sun Times. I’m a longtime friend, ardent fan and two-time record producer of Erwin’s, and had lunch with him soon after the article […]

RIP Annie Ross: Her last stand with Jon Hendricks

Annie Ross, who died July 21 at age 89, sold “Loch Lomond” as a seven-year- old in the Little Rascals with brass equal to her hero in “Farmers Market” hawking beans. The child of Scottish vaudevillians, she was maybe never shy. In 2002 I reported on her last stand with fellow vocalese icon Jon Hendricks, […]