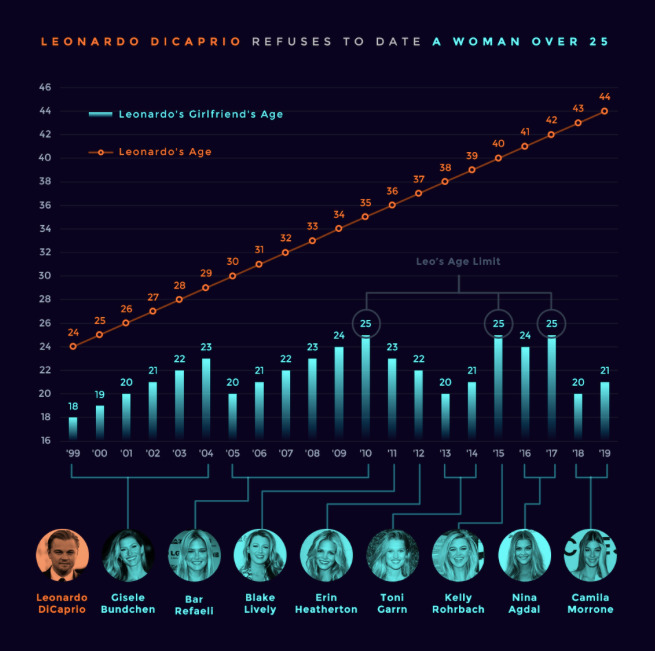

As I grow older, I find that my personal definition of what it means to be beautiful is becoming far more encompassing. To be sure, I can’t remember ever having had a perfectly clear-cut “type,” though I’ve always had something of a weakness for cat-like faces. My past girlfriends look nothing like one another. Nevertheless, I’m impressed by the range of women who strike me these days as attractive (I’m almost entirely blind to male beauty, in much the same way that Mister Rogers couldn’t tell the difference between red and green). Unlike Leonardo DiCaprio, who is notorious for his insistence on dating only women of a very certain age, I find beauty in places where once I would never have thought to look. All ages, all facial types, all shapes and sizes: the possibility of being beauteous, as Rimbaud called it, now seems to me very nearly without limit. Indeed, I seem to be approaching the state of mind described by a character in Eric Rohmer’s Love in the Afternoon, albeit for a reason utterly and fortunately different from that of the unhappy fellow who speaks the line: “Since my marriage I have found all women beautiful.”

What no longer catches my eye, however, is youthful prettiness, the unlined state of unearned grace whose external appearance medical science has at long last found a way to simulate and which DiCaprio is by no means the only movie star to require of his consorts. It is wasted on me, whether in its natural form or in the chemically assisted simulacra that are easy enough to spot, especially on the already-known faces of celebrities unwise enough to resort to such assistance.

On the contrary, it is the distress marks of experience that speak most powerfully and eloquently to me in my late middle age. I think this is because I favor the company of people whose lives have taught them something of how the world works, and who have profited from what they’ve learned. It isn’t hard to detect the presence of such knowledge in those who have it, any more than it is to be able to tell whether people are bright before they utter a single word. All you have to do is look—and to understand what you’re seeing.

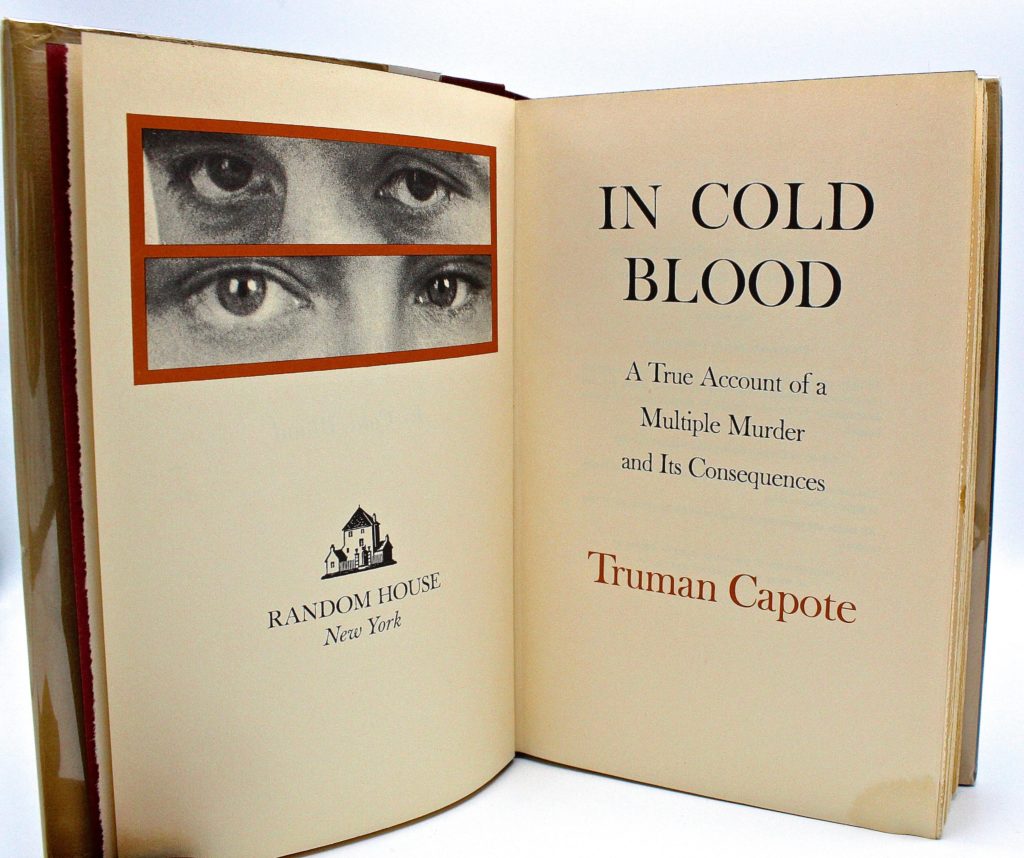

Experience, like intelligence, reveals itself best through a person’s face, and above all through the eyes. No amount of Botox, however cunningly administered, can offset the lack of a comprehending gaze. Conversely, it is the eyes that reveal no less immediately the cruelty and inward disorder of a person who is full of rage and capable of great evil.

The frontispiece of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood consists of tightly cropped photographs of the eyes of Perry Smith and Richard Hickock, an image that was surely inspired by this passage from the book:

Marie examined the front-view and profile photographs of Smith: an arrogant face, tough, yet not entirely, for there was about it a peculiar refinement; the lips and nose seemed nicely made, and she thought the eyes, with their moist, dreamy expression, rather pretty—rather, in an actorish way, sensitive. Sensitive, and something more: “mean.” Though not as mean, as forbiddingly “criminal,” as the eyes of Hickock….

Marie, transfixed by Hickock’s eyes, was reminded of a childhood incident—of a bobcat she’d once seen caught in a trap, and of how, though she’d wanted to release it, the cat’s eyes, radiant with pain and hatred, had drained her of pity and filled her with terror.

Vultus est index animi, said the Romans: the face is the index of the mind. I recalled that dusty tag as I sat in a hot tub last week and caught sight of a woman who looked from a distance to be in her late forties or early fifties. Time was when I wouldn’t have thought twice about her, but I know better now, and I said to myself, You know, she’s really quite attractive. But then I saw the slack, dull expression on her face, and that was that.

Not so Mrs. T, with whom I fell in love at first sight (really and truly!) fourteen years ago, at which time we were both a couple of months shy of our fiftieth birthdays. What I saw in her that fateful, blessed night was a face full of energy and determination, anchored by a lively pair of eyes into which I knew at once that I longed to gaze every day for the rest of my life.

I soon found out that Mrs. T didn’t like the way she looked, something that she has in common with every other attractive woman I’ve known. As Stephen Maturin says to Jack Aubrey in Master and Commander, “I have never yet known a man admit that he was either rich or asleep.” So be it: all I can tell you is that she looks to me like a woman who has lived a full life, and who paid attention while she was living it. I would rather look at her than anyone else in the world.

Our Girl in Chicago, my best friend, is another person whose eyes tell you what she is, smart and funny and almost painfully sensitive. She, too, is a beauty who is unaware of it, the only good thing about which is that it makes it possible for me to tell her as often as I please that she is beautiful. That beauty was as yet unformed when we first met, not long after she graduated from college and came to work for my then-publisher, but she’s since had time to grow into it, and today she has the knowing eyes of a mature woman who, like Mrs. T, has learned the hard lessons of experience without being hardened by them.

For my part, I prefer the real right thing, about which one might well say what E.M. Forster and Eric Crozier said about goodness in their libretto for Benjamin Britten’s operatic version of Billy Budd: “There is always some flaw in it, some defect, some imperfection in the divine image, some fault in the angelic song, some stammer in the divine speech.” Such, too, is the nature of true beauty: there is always some flaw in it. That is what makes it human—and lovable.

* * *

“No Matter What Shape Your Stomach’s In,” an Alka-Seltzer commercial created by Mary Wells Lawrence in 1965 for Jack Tinkers & Partners:

A scene from The Truth About Cats & Dogs, written by Audrey Wells, directed by Michael Lehmann, and starring Janeane Garofalo and Ben Chaplin: