This essay about James Gould Cozzens’ Guard of Honor originally appeared in National Review in 2009. It’s never been reprinted, nor has it been available on line until now. I post it in order to draw your attention to a near-forgotten book that I consider to be one of the best American novels of the twentieth century.

* * *

Novelists don’t always write about what they know, but when something interesting happens to them, it usually winds up in a book. World War II was the most interesting thing that happened to most of the American novelists who served in it, and most of them duly produced novels based on their experiences, nearly all of which are forgotten. (Who now reads Irwin Shaw’s The Young Lions or Gore Vidal’s Williwaw?) The more I read in the literature of the Good War, the more certain I am that it is in memoirs like Donald R. Burgett’s Currahee! and E.B. Sledge’s With the Old Breed and the dispatches of such journalists as A.J. Liebling and Ernie Pyle that the very best American wartime writing is to be found—with a single exception. Of the countless novels of World War II written by American vets, the only one to which I return regularly is James Gould Cozzens’ Guard of Honor.

If you’ve never heard of Guard of Honor, you’re not alone. Though it won a Pulitzer Prize in 1949, it is as poorly remembered as the rest of Cozzens’ novels, and I doubt that it is ripe for revival. Set in a stateside Army Air Force base nine months before D-Day, most of its main characters are desk jockeys who almost certainly never made it to Europe or the South Pacific. Not surprisingly, nobody ever thought to turn the exploits of these indispensable yet invisible warriors into a movie; probably, nobody ever will. Yet Guard of Honor is a great novel all the same, the only English-language novel of World War II that can withstand comparison with Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of Honour.

If you’ve never heard of Guard of Honor, you’re not alone. Though it won a Pulitzer Prize in 1949, it is as poorly remembered as the rest of Cozzens’ novels, and I doubt that it is ripe for revival. Set in a stateside Army Air Force base nine months before D-Day, most of its main characters are desk jockeys who almost certainly never made it to Europe or the South Pacific. Not surprisingly, nobody ever thought to turn the exploits of these indispensable yet invisible warriors into a movie; probably, nobody ever will. Yet Guard of Honor is a great novel all the same, the only English-language novel of World War II that can withstand comparison with Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of Honour.

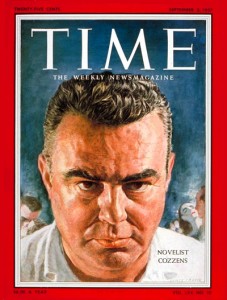

Cozzens, who died in 1978, is one of the least likely people to have made the cover of Time—though it wasn’t Guard of Honor that put him there. By Love Possessed, the 1957 best seller that won Cozzens a bit more than fifteen minutes’ worth of fame, was the occasion for an otherwise sympathetic cover story that portrayed him as a misanthropic grouch. Dwight Macdonald cherry-picked the story for quotes that he used to devastating effect in “By Cozzens Possessed,” a no-holds-barred assault on By Love Possessed that dismissed it as a windy exercise in middlebrow mediocrity. Alas, the essay was both clever and not entirely wrongheaded—By Love Possessed is the weakest of Cozzens’ major novels—and it did so much damage to his reputation that his masterpiece vanished in the rubble.

To read Guard of Honor after reading “By Cozzens Possessed” is to wonder whether Macdonald might possibly have had some other James Gould Cozzens in mind. Guard of Honor is almost as long as By Love Possessed, but it’s written with a disciplined tautness that makes it feel much shorter. At the same time, anyone familiar with both books will see at once that they are, like all of Cozzens’ novels, cut from the same cloth. He had many settings but only one subject—the near-insurmountable obstacles that stand in the way of shedding youthful illusions and seeing the world as it really is—and in Guard of Honor he explored it so fully as to leave himself with nothing new to say for the remainder of his writing life.

Guard of Honor takes place during forty-eight hours at Ocanara Army Air Base, located somewhere in central Florida. Most of the novel’s characters are seen through the eyes of Colonel Norman Ross and Captain Nathaniel Hicks, neither of whom is a career officer. Ross is a sixty-year-old judge, Hicks a thirty-eight-year-old magazine editor. Both men suppose themselves to be clear-eyed realists, and both find in due course that they still have more than a few things to learn about human nature, theirs included: “There never could be a man so brave that he would not sometime, or in the end, turn part or all coward; or so wise that he was not, from beginning to end, part ass if you knew where to look; or so good that nothing at all about him was despicable.”

The occurrence that opens their eyes is a short-lived protest by a group of black pilots who are enraged when they are told that they cannot be admitted to the whites-only Ocanara officers club but must stick to their own segregated facility. This protest, which is based on a real-life incident, is like a stone tossed in the water of Cozzens’ complicated plot. Its ripples touch all of the novel’s characters, most of whom did not see what happened and only know about it through more or (mostly) less accurate scuttlebutt. Colonel Ross’ job is to paper over the protest and protect the reputation of Ira Beal, the base commander, a talented but immature pilot who is being groomed by his Pentagon superiors for bigger things.

None of this is the stuff of which John Wayne movies are made, but it is enthralling all the same, for in telling the story of the protest and its aftermath, Cozzens takes the reader on an infinitely knowing guided tour of Ocanara, in the process showing how things get done in wartime, how they go wrong, and how they get fixed—or not. Along the way we meet people from every walk of life, each of whom is sketched with arresting exactitude. If that makes Guard of Honor sound like Grand Hotel, rest assured that Cozzens never stoops to once-over-lightly typecasting. His characters, the women included, are individual and recognizable, and before long you find yourself caring very deeply about what is to become of them.

Though we see much of Captain Hicks, who finds himself pulled almost unwittingly into an extramarital involvement with a lonely WAC lieutenant who is the novel’s most sensitively drawn character, it is Colonel Ross whose voyage of self-discovery lies at the heart of Guard of Honor. He is, like Melville’s Captain Vere, an old man who has experienced much—one of the Wright brothers taught him to fly—and a lifetime of labor in the vineyards of politics has taught him equally hard lessons about the differences between what men say in public and what they do in private. Yet he is taken aback to find that there are younger men of higher rank who cast an even colder eye on the inevitable limitations of their fellow men, and is chastened by the knowledge that he is, like most of us, a man whose experience “fitted him to advise others, rather than himself.”

Colonel Ross, we learn, is both a stoic and a pragmatist. Though he has come to the reluctant conclusion that life has no meaning, he also knows that the war against the Axis must be won if unimaginable horrors are not to be loosed on the world, and that in the long run it will likely be won less by heroism than by sheer determination: “A man must stand up and do the best he can with what there is….If mind failed you, seeing no pattern; and heart failed you, seeing no point, the stout, stubborn will must be up and doing. A pattern should be found; a point should be imposed.”

Part of what makes Guard of Honor so memorable is that its disillusion is untainted by cynicism. Cozzens spent most of the war pushing paper in the Pentagon, an experience that would have inspired the average novelist to write a very different kind of book. Instead he came away believing that most of the people whom he met while in uniform had done their best to do the right thing and, more often than not, did it pretty well.

Part of what makes Guard of Honor so memorable is that its disillusion is untainted by cynicism. Cozzens spent most of the war pushing paper in the Pentagon, an experience that would have inspired the average novelist to write a very different kind of book. Instead he came away believing that most of the people whom he met while in uniform had done their best to do the right thing and, more often than not, did it pretty well.

The result of his experience is a book that might well be described as the inverse of Catch-22, just as Cozzens himself was as different from Joseph Heller as a man can be. Guard of Honor, to be sure, is full of pointed humor, much of it at the expense of prigs. Yet Cozzens never makes fun of anyone who hasn’t earned it, nor does he suggest that the Army’s flaws and foolishnesses negate the purpose for which it exists. Midway through the novel, Captain Hicks compares the “simple, unlimited integrity” of Regular Army officers like General Beal who “accepted as the law of nature such elevated concepts as the Military Academy’s Duty-Honor-Country” to the more fashionable views of “men who considered it the part of intelligence to admit that Honor was a hypocritical social sanction protecting the position of a ruling class; or that Duty was self-interest as it appeared when sanctions like Honor had fantastically distorted it.” Amused by the thought of what the general would make of such high-minded folk, Hicks imagines him retorting, “What the hell kind of person thought things like that?”

That General Beal’s “simplicity” should be tacitly presented by Cozzens as admirable goes a long way toward explaining why Catch-22 is far better known than Guard of Honor—especially by youngsters who know little of the way the world works. When I was in high school, I was sure that Catch-22 was one of the great American novels. Now I find the baby-black antics of Yossarian and his jeering buddies to be embarrassingly jejune, whereas my admiration for Guard of Honor deepens every time I return to it, as I do every year or two. Perhaps I would admire it less if I had had to go to war, but I doubt it. One need not have dodged bullets to know the sharp tang of truth.

•

•

I spent last week in Spring Green, the tiny Wisconsin village that is home to

I spent last week in Spring Green, the tiny Wisconsin village that is home to  One of the books that I brought with me to Spring Green was William Haggard’s Venetian Blind, a spy novel whose cast of characters includes a Bonnard-loving industrial magnate who doesn’t know much about art but knows what he likes:

One of the books that I brought with me to Spring Green was William Haggard’s Venetian Blind, a spy novel whose cast of characters includes a Bonnard-loving industrial magnate who doesn’t know much about art but knows what he likes: That’s not quite me, but it came pretty close last week. Instead of wrestling with the eternal and insoluble problems that are my customary lot, I allowed myself to relax into the present. I’m back on the East Coast now, reunited with Mrs. T and more than happy to be. Hectic and harassing though it sometimes is, I love my life and am at all times grateful for the increasingly improbable good fortune that permits me to make a living writing about the arts. But man cannot live by work alone, no matter how much he loves it, and so it was both good and necessary for me to slip the traces and spend a few days under the bright blue skies of Wisconsin, enjoying the restorative pleasures of doing nothing in particular.

That’s not quite me, but it came pretty close last week. Instead of wrestling with the eternal and insoluble problems that are my customary lot, I allowed myself to relax into the present. I’m back on the East Coast now, reunited with Mrs. T and more than happy to be. Hectic and harassing though it sometimes is, I love my life and am at all times grateful for the increasingly improbable good fortune that permits me to make a living writing about the arts. But man cannot live by work alone, no matter how much he loves it, and so it was both good and necessary for me to slip the traces and spend a few days under the bright blue skies of Wisconsin, enjoying the restorative pleasures of doing nothing in particular.