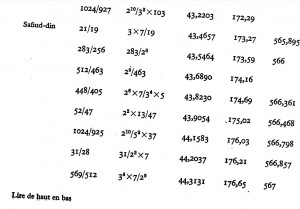

Thanks to an unencumbered and rather inspired summer, I am more than halfway through an evening-length collection of pieces for three microtonally retuned Disklaviers. I’m calling it Hyperchromatica, because a melodic reliance on intervals smaller than a quarter-tone is about the only stylistic constant. 33 pitches to the octave. Most of the pieces have polytempo structures, several are polytonal as well, which I had always wanted to try doing in just intonation. I’m unveiling the nine movements I’ve finished, which total 83 minutes. Scores, tuning, and program notes are here. Three of the pieces I had put up last year, and I finished six more recently.

– Orbital Resonance, 11:31; a meditation on planetary motions, beginning on the 65th and 66th harmonics of E-flat, and ending with the 54th, 55th, and 56th.

– Futility Row, 8:53; my sly Western noir movement, but with more subtlety of large-scale harmonic structure than I’ve yet achieved elsewhere.

– Pavane for a Dead Planet, 9:04; a thoroughly Romantic take on a Baroque form, but with some interesting intervals and rhythms.

– Star Dance, 6:40; a self-indulgent immersion in melodies of the smallest feasible steps.

– Dark Forces Signify, 8:17; this is my tribute to Black Lives Matter (matter being a difficult verb to synonymize). The bass motive is from Julius Eastman, and the simplicity sets off the hyperchromatic voice-leading well.

– The Lessing Is Miracle, 9:36; the title is an enigma found in all capitals in one of Julius’s scores, and the texture was initially inspired by one of his pieces. This one makes my wife nervous. It is odd.

– Romance Postmoderne, 8:36; a nostalgic ballad, and the first piece I wrote in this tuning.

– Liquid Mechanisms, 13:19; a big Jackson Pollock mural of various panels, the complexity of each clarified, hopefully, by internal (and nonsynchronized) repetition. Nested tuplets are a recurring motif.

– Galactic Jamboree, 7:15; the gonzo finale to the whole set.

I’m planning another five or six movements, but who knows if I’ll stop then? The size of the project serves two purposes: one to put out a two-CD set for my own vanity, the other so that, in the unlikely case anyone is ever foolhardy enough to want to stage the entire series with actual Disklaviers, it will at least be a large enough event to justify the expense and trouble. But for now I can do it all on my computer. As Lou Harrison said to John Luther Adams, “We’re the do-it-yourself composers.” I should also report, though, that living so long inside this elegant tuning keeps revealing more and more of its facets and capabilities.