Last week I had the privilege, pleasure, and honor to give the keynote address at the Canadian Arts Summit–an annual gathering of the board chairs, executive leaders, and artistic leaders of Canada’s major cultural institutions. It was a terrific conference all around. Here is a link to a transcript of my keynote address. The talk was also live streamed and, as I understand it, a video will eventually be available for download.

Last week I had the privilege, pleasure, and honor to give the keynote address at the Canadian Arts Summit–an annual gathering of the board chairs, executive leaders, and artistic leaders of Canada’s major cultural institutions. It was a terrific conference all around. Here is a link to a transcript of my keynote address. The talk was also live streamed and, as I understand it, a video will eventually be available for download.

Following a preamble (which highlights some of the key themes that I’ve been circling around for the past decade), the talk is divided into three parts:

Part 1: Can we talk about our aesthetic values?

Do aesthetics get discussed at your own arts organization? If so, who is involved in the discussion?

- The artistic staff?

- All senior managers?

- Board members?

- Box office staff and front of house?

- The janitorial staff?

Generally my experience has been that it is actually quite difficult for arts leaders, staffs, boards, and other internal and external stakeholders to talk about aesthetics, honestly, in this changed cultural context; but I think we must.

Part 2: Can we talk about how a season comes together? (Hat tip to David Dower at ArtsEmerson …)

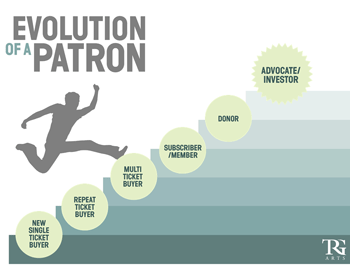

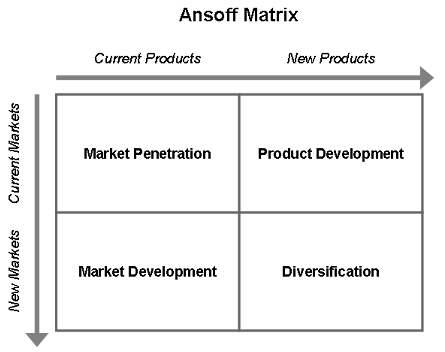

How does a season, or a collection, come together? What’s the relationship between the economics, ethics, and aesthetics of our organizations? What’s the mutual dependence between judgments of artistic excellence; the non-negotiable principles that uphold organizations’ core values; and the willingness for particular bodies to pay? What holds everything together? Dare we ask?

Part 3: What does responsible artistic leadership look like? What’s the work in 2018?

The subsidized arts not only can—but must—play a vital, humanizing role in any society but to play that role, in these times, we must regenerate individual arts organizations. What does that work look like? (I share a few ideas.)

Many thanks for reading and sharing any thoughts!

[contextly_auto_sidebar]