See article, What if art centers existed to ignite radical citizenship? by Deborah Cullinan.

Joe Horowitz has written a stirring essay on the Metropolitan Opera, New York City Ballet, and New York Philharmonic on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Lincoln Center. In response, ArtsJournal has asked a number of people to consider the essay and to weigh in on a series of questions (paraphrased):

Is artistic leadership at America’s arts institutions lacking? Moreover, is this at the root of declining relevancy of the arts? Is something more, or better, needed from America’s arts institutions, particularly at this vexing and critical time?

This essay explores these questions through the lens of the American theater. At the heart of this essay rests the paradox of the Public Arts Institution—a paradox captured beautifully in this passage from a 1970 essay by Arena Stage co-founder, Zelda Fichandler, Theatres or Institutions?[1]

I am not very strong on community giving, except perhaps when it represents only a small percentage of the total. I think we could well do without the hand that rocks the cradle, for the hand that rocks the cradle will also want to raise it in a vote and mix into the pie with it. For while a theatre is a public art and belongs to its public, it is an art before it is public and so it belongs first to itself and its first service must be self-service. A theatre is part of its society. But it is a part which must remain apart since it is also chastiser, rebel, lightning rod, redeemer, irritant, codifier, and horse-laughter.

This is a paradox I also wrestled with in an essay published in the most recent issue of Artivate called On Entrepreneurialism and Publicness (or Whose Theatre is it, Really?).Â

Part I: Are We Weeding, or Breeding, Artistic Leadership Out of the Field?

Joe Horowitz’s story is a tale of three organizations, only one of which (New York City Ballet) succeeded in changing the face of its art form. What made the difference at the Ballet? By my reading, there was first and foremost a will on the part of both Balanchine and his impresario, Kirstein, to do so; and second, conditions were ripe for these institutional entrepreneurs to make their move.

Last year I worked on a case study on the Margo Jones Theatre, founded in 1947 (in Dallas, Texas) and hailed by most theater historians as the prototypical modern resident theater. Jones produced exclusively new plays and classics. In an average season Jones produced 4-5 premieres and two classics; in contrast, of 23 resident theaters surveyed in 1965 by journalist Sandra Schmidt, 15 produced no new plays at all and four produced only one.[2]Â At the time, most resident theaters exemplified the vibrant museum model described in Horowitz’s essay.

Historians often chalk this up to a discomfort with new fare on the part of both institutional leaders and their audiences. Perhaps. It seems Jones overcame discomfort by reading a minimum of one new script every day of her life from her college days onward and, more importantly, she made her audience comfortable with new fare through the same process: repeated exposure.

Like Balanchine, Jones had a vision and the will to execute it. Importantly, she also had a business manager who supported her commitment to new plays and a board of directors that gave her free reign. Equally as important, resident theater in America was in its pioneer period. But the first condition is critical. Jones was devoted to playwrights and preached far and wide that nonprofit regional theaters had a moral duty to produce new plays being rejected by the commercial stage, in lieu of relying on Broadway revivals–fare favored by both commercial winter stock companies and community theaters at the time.

We seem to have few such zealots running American LORT theaters these days.

Why is that?

I don’t believe it’s because none exist.

Consider the driving emphasis on instilling arts institutional leaders with business skills since 1960; the now mandatory requirements of a track record of raising money and delivering box office hits (that will fill Broadway-sized venues) to attain the job of artistic director at a major theater; the lack of artists on nonprofit boards, or even many individuals with an aesthetic sensibility; and the dramatic power shift from artist-leaders to business-leaders, generally.

Maybe we have been breeding, or weeding, artistic leadership out of the field?

Margo Jones didn’t like to raise money from the community, she demanded 100% control of her theater, and she walked into the job interview saying to the board, in essence: Count me out if you are planning to be a theater of the past, “striving to exist on box-office hits,†as I am only interested in creating “a true playwright’s theatre, presenting original scripts and providing playwrights with an outlet for their work.â€[3]

If Margo Jones were applying to run an American theater in the hinterlands of the US today she probably wouldn’t stand a chance.

Part II: Artists are Getting it Done … But Are Institutions Getting in the Way?

I recently had the privilege of attending a Salzburg Global Seminar called The Art of Resilience: Creativity, Courage and Renewal. Among many inspiring presentations was one by artist Anida Yoeu Ali, a first generation Muslim Khmer woman born in Cambodia and raised in Chicago. Anida talked about a number of her works, including a performance installation called The Red Chador: Thresholds, created for a 2016 Smithsonian event called Crosslines: A Culture Lab on Intersectionality. The work asked viewers: “Can we accept a Muslim woman as a patriotic woman?â€

The Red Chador: Threshold, Washington DC, USA | May 28-29, 2016. Commissioned by Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center. Performance by Anida Yoeu Ali. Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Photo Courtesy of Les Talusan

Over breakfast one morning I asked Anida, “So how would you respond to the question, ‘What is the role of the artist post-Trump?†and she said, “Same as always. No different. Get up and do the work.â€

The day after the election Anida took to the streets of Seattle, where she is now based, wearing the red, glittering chador she created for the Smithsonian performance installation and holding a sign that on one side said, I AM A MUSLIM and, on the other, BAN ME.

The Red Chador: The Day After, Seattle, USA | Nov 9, 2016. Performance by Anida Yoeu Ali.  Photo courtesy of Studio Revolt.

What’s my point?

Artists are doing something about it, same as always.

However, most artists depend upon institutional outlets for protection, platforms, and resources for that something to be fully realized.

To this very point, the New York Times recently ran an article on a new play by Robert Schenkkan, written in a “white-hot fury†in one week. Characterized as a “disquieting response to the Trump era,†it’s called Building the Wall.  Schenkkan says in the article:

We no longer live in a world that is business as usual—Trump has made that very clear—and if theater is going to remain relevant, we must become faster to respond.

While the article goes on to mention that a group of theaters has committed to producing the play within the next few months, it’s worth noting that (a) this sort of response is exceedingly rare; and (b) the theaters that have stepped up are largely part of a small alliance of exemplary midsized theaters (the National New Play Network) that has fought the past decade or so to shift stultifying practices around new play development in the US.

Most institutions are not able to respond quickly to artists (doing something about it) in large part because artists exist outside of institutions rather than within them. While resident theaters were initially idealized as homes for actors, writers, and designers what they have become in reality is homes for administrators and technicians. Even when artists are in residence they quite often have minimal (if any) power within institutions, or influence on them. And we have had a number of instances of institutional cowardice (if not censorship) in recent years. (See, e.g. this article on the experience of Anida Yoeu Ali and Gregg Deal at the Smithsonian event mentioned above.)

I have heard playwrights say that they write for television these days not only because they make more money but because it is a more creative and validating environment than the nonprofit American theater. That is a sobering thought.

Perhaps any lack of courage, vision, or moral imagination in arts organizations is related to the extent to which arts leaders have managed risk by disempowering artists or placing them outside the institution?

Part III: Do arts leaders identify too much with their upper middle class donors?

I was at a conference a few weeks ago and heard a development staffer bemoaning over her morning croissant that she had spent the better part of the prior two weeks trying to learn everything she could about some Ultra-High-Net-Worth-Couple in her city so that her institution could launch a stealth courtship and, with any luck, land a major gift. She commented that, as far as anyone could tell, this couple had never stepped foot in the doors of the institution. She fretted over the fact that she was dedicating every working moment to deeply understanding two wealthy people with no relationship whatsoever to the institution; while nary a nanosecond was being expended trying to learn about the values, hopes, dreams, and challenges of the loyal patrons who were not in a position to make an extraordinary gift to the institution.

While donor research and cultivation has become a serious science, the ideology driving such behavior has been with us since the founding of the nonprofit-professional arts sector in the US. I am amazed that we are able to say with a straight face that America’s 20th century nonprofit-professional theater companies were largely established to serve the general public when many institutionalized a practice (at their inceptions) that would ensure they paid attention to the needs of the upper middle class at the expense of all others.

In the 1960s Danny Newman persuaded theaters that it was better (not just economically better, but morally better) to focus their time and resources on the 3% of the population that is inclined to subscribe and to ignore everyone else. Though some artistic directors rebelled mightily against this approach in the theater industry—Richard Schechner and Gregory Mosher were among the most vocal who noted that it was undemocratic and had a stultifying effect on programming—it was embraced wholeheartedly by a majority of institutions. This was in large part because it was strongly encouraged by the Ford Foundation and its proxy at the time, Theatre Communications Group.

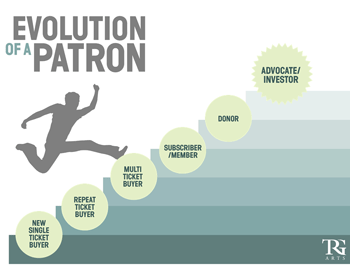

Today marketing firms promulgate customer relationship management models like this one promoted by TRGÂ Arts. This sort of philosophy upheld over time will invariably orient an organization toward caring more about those who can buy more tickets and donate more money.

Arts institutions cannot uphold Zelda Fichandler’s notion of the theatre as belonging to the public but first belonging to itself if they are, essentially, social clubs for the upper middle class. The institution cannot be “chastiser, rebel, lightning rod, redeemer, irritant, codifier, and horse-laughter†if it has neither independence nor publicness.

Perhaps a driving focus on cultivating the patronage of the upper middle class has skewed the politics and purposes of arts institutions, and also has been a major factor in declining relevancy? On the most fundamental level nonprofit art institutions are among the cultural spaces that are able to bring people together across divides on equal terms—a vital function that is, at times like these, in and of itself a political act. However, it seems we have too gladly ceded that role to sports and (lately) to some exemplary libraries around the world (see, e.g., the library parks in Colombia) that have transformed their purposes for the 21st century.

Part IV: Good We Are Awake. Now, Can we Stay Awake?

Shortly after Trump was elected a particular a phrase from Tony Kushner’s masterpieces Angels in America, parts I and II began to appear on my Facebook feed, which is to a great extent populated by liberal arts types like me. That phrase: “The Great Work Begins.â€

The statement, in turns hopeful and harrowing depending on its context in the plays, provoked two questions for me:

What is our Great Work in the arts? (which I addressed in this Jumper post); and

Why is this Great Work beginning only now, after Trump’s election?

Put another way, why does it so often take a crisis for those of us working in the arts, in the so-called civic sphere, to engage with the struggles, the pain, the hopes, the dreams, the fears … of our communities-at-large?

The extraordinary observer of the human condition, writer Rebecca Solnit, reflects in her beautiful book, Hope in the Dark:

Americans are good at responding to crisis and then going home to let another crisis brew.

She says this is, in part …

… because we tend to think that political engagement is something for emergencies rather than, as people in many countries (and Americans at other times) have imagined, as part and even a pleasure of everyday life.

“The problem†as she puts it, “seldom goes home.â€

Unlike television (and libraries) the American theater didn’t use the Digital Revolution combined with the Great Recession as an opportunity to radically transform itself so as to become more relevant, more vibrant, more accessible, more vital—and yes, more economically sustainable.

It seems we have another shot as, for many in the arts sector, Trump seems to represent a wake-up call.

Perhaps now is the time to prioritize artistic vision over business skills; to grant artists primacy within the arts institution; and to shift attention from wealthy donors to the community-at-large. Perhaps now is the time to embrace the paradox of being Public Arts Institutions: a part of society—but a part which must remain apart in order to fulfill its multifaceted role as “chastiser, rebel, lightning rod, redeemer, irritant, codifier, and horse-laughter.”

Finally, perhaps engaging in public affairs for the next four years will remind arts institutions that this is not the Great Work we must do now, this is the everyday work–the doing something about it–we should have been doing the past 30 years and that we must continue to do post 2020.

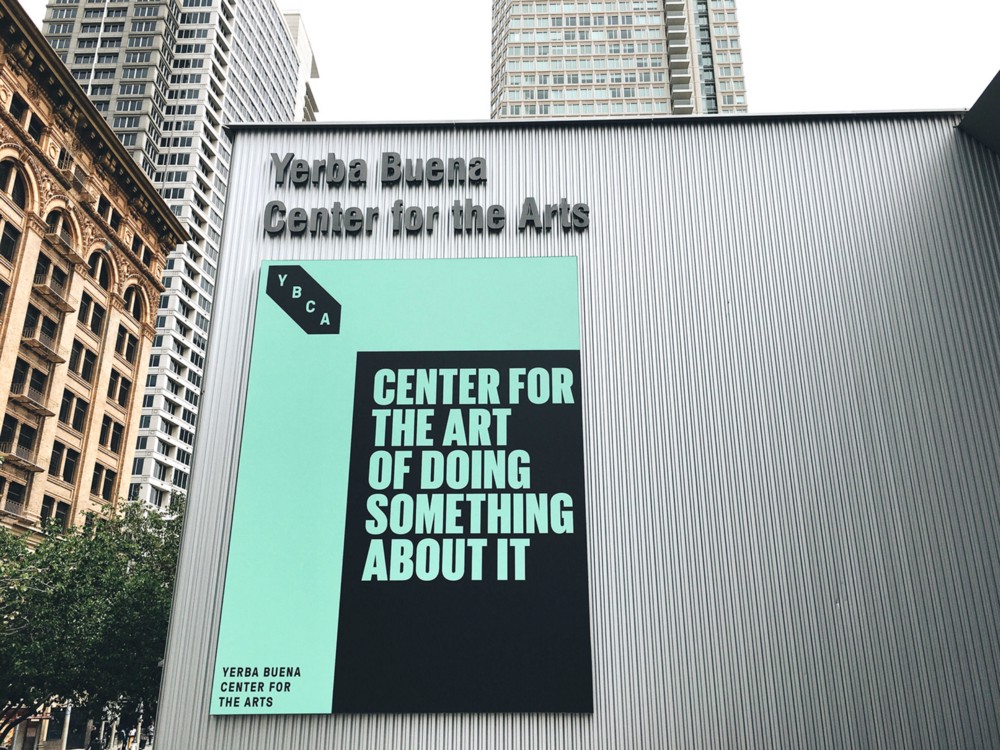

PS – Huge shout out to Deborah Cullinan at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. I love her notion of art centers existing to ignite radical citizenship and I love the YBCA campaign that resulted in the tagline pictured in the photo at the top of this post, which was an inspiration for this piece.Â

***

[1] Fichandler, Z. (1970). Theatres or Institutions? The American Theatre 1969-70: International Theatre Institute of the United States, Volume 3. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons), p. 110.

[2] Schmidt, S. (1965). The Regional Theatre: Some Statistics. The Tulane Drama Review, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Autumn, 1965), pp. 50-61.

[3] Sheehy, H. (1989). Margo: The Life and Theatre of Margo Jones. (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press), p. 88.