The Philanthropy News Digest recently sent me a bulletin with the headline, “Arts Funding Does Not Reflect Nation’s Diversity, Report Finds†which linked me to an AP Newsbreak article with the headline “Report finds arts funding serves wealthy audience, is out of touch with diversityâ€. My initial thought was, “Seriously? We need a report to tell us this?†The report, Fusing Arts, Culture, and Social Change: High Impact Strategies for Philanthropy, was produced by the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy and written by Holly Sidford.

The Philanthropy News Digest recently sent me a bulletin with the headline, “Arts Funding Does Not Reflect Nation’s Diversity, Report Finds†which linked me to an AP Newsbreak article with the headline “Report finds arts funding serves wealthy audience, is out of touch with diversityâ€. My initial thought was, “Seriously? We need a report to tell us this?†The report, Fusing Arts, Culture, and Social Change: High Impact Strategies for Philanthropy, was produced by the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy and written by Holly Sidford.

Here are a couple paragraphs from the executive summary:

Every year, approximately 11 percent of foundation giving – more than $2.3 billion in 2009 – is awarded to nonprofit arts and culture. At present, the vast majority of that funding supports cultural organizations whose work is based in the elite segment of the Western European cultural tradition – commonly called the canon – and whose audiences are predominantly white and upper income. A much smaller percentage of cultural philanthropy supports the arts and traditions of non-European cultures and the non-elite expressions of all cultures that comprise an increasing part of American society. An even smaller fraction supports arts activity that explicitly challenges social norms and propels movements for greater justice and equality.

This pronounced imbalance restricts the expressive life of millions of people, thus constraining our creativity as a nation. But it is problematic for many other reasons, as well. It is a problem because it means that – in the arts – philanthropy is using its tax-exempt status primarily to benefit wealthier, more privileged institutions and populations. It is a problem because our artistic and cultural landscape includes an increasingly diverse range of practices, many of which are based in the history and experience of lower-income and nonwhite peoples, and philanthropy is not keeping pace with these developments. And it is a problem because art and cultural expression offer essential tools to help us create fairer, more just and more civic-minded communities, and these tools are currently under-funded.

I am as discouraged as anyone by where many (but certainly not all) private foundations and wealthy individual donors give their support, and where they do not. However, my sense has never been that this behavior persists (and has perhaps become more pronounced as the demographics of the country are shifting dramatically) because the heads of foundations or the wealthiest donors in America were lacking a report explaining that too much of their money was going to arts organizations producing Western European ‘high art’ for white, upper middle class audiences.

The book Patrons Despite Themselves told very much the same story back in 1983 in its analysis of the ‘indirect’ system of funding the arts (that is, via the tax system rather than via direct grants from government). Feld, O’Hare, and Schuster concluded (among other things):

On balance, income to the arts is paid for disproportionately by the very wealthy and is enjoyed more by the moderately wealthy and the well educated. The demographic characteristics of the audience – the beneficiaries of the government aid – do not vary much across art forms. While the system tends to be redistributive, it is only so in a limited sense: from the very wealthy to the moderately wealthy.

Three of the recommendations in PDT regarding philanthropic decisionmaking are: (1) “decisions should reflect expertise in the subject”; (2) “public decisions in allocation of government support for the arts should reflect many varied kinds of tastes”; and (3) “arts decisionmaking must be independent of malign influence, that is, influence represented by narrow partisan politics or self-serving interests.”

We can see how much traction the authors had in the arts and culture sector with this message given the ‘elitism redux’ (and with more urgency) message in the new National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy report.

This is why I find it ironic when funders throw their arms up in the air, discouraged by declining attendance at ‘out-of-touch’ symphony orchestras and other fine art forms. It would seem that the growing gap between these organizations and their communities exists in large part because they continued to find support and legitimacy from high profile foundations even as they were raising ticket prices and failing to update their programming and becoming increasingly ‘non-representative’ of their communities over the past 30 years.

Moreover, if we are wondering why this decades-old message just doesn’t seem to ‘stick’ and change behavior, it may be worth taking a moment to recognize the “alliance between class and culture†that emerged with the very development of our nonprofit arts system in the US: “High art†was meant to serve the needs of urban elites and the hierarchical distinction between “high culture†and “popular culture†was meant to distinguish not simply two forms of culture but the types of people that patronized these forms of culture (DiMaggio 1982).

We have (and have had) a cultural divide in the US and the arts continue to contribute to it – not all arts, but certainly a large part of the sector that is often heralded as ‘leading’, ‘excellent’ and ‘world class’. You don’t end up with the large majority of your audience being white and wealthy by accident. Nor do you end up with the large majority of your funding portfolio going to assist those organizations that are primarily serving those white and wealthy people, by accident.

This is by design, folks.

I by no means want to suggest that it is a waste of time to periodically document the fact that private funding for the arts continues to primarily support upper middle class white people. This is, perhaps, a message that needs to be transmitted continually if the situation is to change. And, as the report accurately suggests, this issue is becoming more acute as arts funding fails to keep pace with dramatic socio-economic changes that are occurring.

Indeed. Taking the message one step further, I don’t think I’m alone in thinking that organizations whose value is reliant upon old institutions, old habits, and old social networks (centered around an old concept of ‘the cultural elite’) may very well find themselves on the wrong side of a cultural change in the years to come.

Arts organizations and their funders would seem to have a choice: be part of the change or fight to the death to uphold the dying system that for decades gave their work meaning. Perhaps their own survival (if not an interest in fairer and more civic-minded communities and a sincere desire to upend social norms and support social change) will ultimately prompt some of these institutions to change their behaviors?

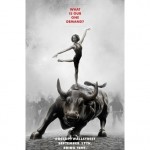

Poster designed by adbusters for #OccupyWallStreet.