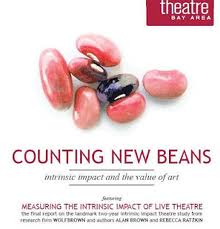

Clay Lord and the fine folks at Theatre Bay Area have a new publication out: Counting New Beans: Intrinsic Impact and the Value of Art, which includes interviews with 20 prominent artistic directors and essays by Alan Brown, Rebecca Ratzkin, Arlene Goldbard, Rebecca Novick, and Clayton Lord. It also includes an interview with yours truly.

Clay Lord and the fine folks at Theatre Bay Area have a new publication out: Counting New Beans: Intrinsic Impact and the Value of Art, which includes interviews with 20 prominent artistic directors and essays by Alan Brown, Rebecca Ratzkin, Arlene Goldbard, Rebecca Novick, and Clayton Lord. It also includes an interview with yours truly.

Here’s an excerpt from my long and winding conversation with Clay Lord. I’ve edited together excerpts (elipses mark missing sections) from two different parts of the interview.

Clay Lord: You’ve written about “creative destruction,” this idea that we either need to take control of our growth and make decisions about what survives, or natural forces will do it for us. But what is the rubric for understanding where the culling of the herd needs to happen, and who does the culling? Foundations? Market forces? Attendance figures? What are the evaluative terms? If the art isn’t going to stop, then how do the organizational structures decrease? Who decides? Who are the arbiters of which organizations are “valuable,” and what are the terms?Â

DER: Artists and communities make up a constantly evolving and changing environment. It’s the institutions that are stuck, holding onto beliefs and practices about what is or is not [a] “legitimate” [artistic experience] and denying the changing tastes, habits and demographics of their communities. […] When we say we need to try to find a way to make things “more sustainable,” what are we talking about? Sustaining middle class livings for those salaried professional administrators that have them? Sustaining the capacity for artistic risk-taking? Sustaining broad and deep community engagement with the theatre? The “what” is really important. And if we’re talking about nonprofit, mission-driven organizations, then we need to be able to answer the “what” with regard to the social value we are trying to sustain or create.

We keep saying we want to see the next thing arrive, but at the same time desperately try to preserve what we’ve already created. It’s very difficult to do both; most often, you need to destroy the old in order to allow for the emergence of the new. This is the idea behind “creative destruction.” […]

I think the “impact” question makes the field a little nervous—and so does the supply/demand conversation—because we sense that we’ve arrived at a day of reckoning. The money is tight and the environment is hyper-competitive. The conversation has been controlled for a long time by a small group of people. For years we’ve had a field-wide understanding of who were the field leaders, and there was no displacing them.

To some degree we’ve gamed and worked the system to maximum output of whatever could be derived from it, and now we have come to the end of the line. It’s time to start asking ourselves the disruptive questions. Does it make sense to subsidize large resident theatres and not commercial theatres? Does it make sense to subsidize professional theatres and not amateur theatres performing in churches or high school gymnasiums? Does it make sense to subsidize those that are most able to garner patronage from wealthy, culturally elite audiences? […]

We’re rather protectionist in the U.S. nonprofit arts sector because we know, or at least suspect in our gut, that if we start measuring intrinsic impact—testing our assumptions about the impact of the art we make— we might find out that there is greater intrinsic impact from watching an episode of The Wire than going to any kind of live theatre. Or we may find that small-scale productions in churches or coffee shops are just as impactful (or more so) than large-scale professional productions in traditional theatre spaces. Are we prepared, if we find this sort of evidence, to change the way we behave in light of it? […]

Because right now it appears we have a winner-take-all system in the arts. The few at the top continue to grow while the rest of the sector is forced to divide a shrinking pie among an increasing number of organizations. Assuming we’re not going to have significantly more resources coming into the sector, […] can we allow for a different idea to emerge about which are the most important organizations to fund? Who’s at the top? Who’s at the bottom? Who’s considered leading? These are rankings that were established decades ago and it’s nearly impossible for even an incredibly worthy and high-performing entrant to displace one of the ‘pioneering’ incumbent organizations at the top of the pyramid. […]

We need data that can help us see the field differently. Sure, if you rank theatres by budget, if you rank them by how many thousands of people they perform to in a year, then you will continue to rank them 1, 2, 3, as they are currently ranked. […] We need new ways of ordering the sector, and understanding what contributes to a healthy arts ecosystem. A lot of money has come into the sector, but it hasn’t been distributed very well. The ecology is out of balance. […]

Who gets to decide which theatres stay and which go? Well, we have a decentralized, indirect subsidy system, meaning, in theory, “everybody” could get to decide. But in reality don’t we see that those with money get to decide? And by extension, then, friends of those with money are the winners and everyone else loses. And then some say, “No one should decide; we should let nature take its course.” But what do we mean by “nature?” Do we mean that we should let “the market” decide?

That’s not valid. You can’t, on the one hand, say “We have to subsidize this particular form of art in order to compensate for market failure,” and then on the other hand say you’re going to let “the market” decide. Many organizations exist today because someone saw them as meriting support 40 or 50 years ago. Why do we resist the idea that some entity or entities should be able to intervene now and discontinue funding for certain organizations (that seem less worthy or relevant now) and encourage or enable funding for others?

The system does not seem to deal with underperforming organizations proficiently or effectively. And if you can’t eliminate underperforming organizations, over time, they compete with other, more worthy organizations for resources. Of course somebody has to decide. A bunch of ‘somebodies’ has to decide. But how do you coordinate that? This is the challenge with our decentralized, indirect subsidy system.

I’m a big believer in Alan Brown’s work, and what you are doing, and I’m hopeful that it can help reframe the conversation about social value and about what it means to be a “leading organization.” Right now, though, what we know is that major foundations provide an imprimatur; they are able to change the perceptions of organizations as they give money and take it away. The press matters. Service organizations matter. And there are others. Any of these can stand on a bully pulpit and say, “Here are the organizations that we perceive to be leaders.” And if it’s a very different list from the list that we’ve had in our minds for a long time, if the names are not simply those that we’ve historically perceived to be leading, it will begin to shift our understanding of what we mean when we say “leading” (i.e., not just oldest and largest). It also provides leverage to the new leaders, increases their ability to fundraise, and changes the way others perceive them. […]

The formation of the nonprofit arts sector was essentially an effort to create exclusive organizations to serve wealthy people – that was the goal. That was the idea at the outset. We have reached a logical result of having created such a system. Arts organizations are sleeping in beds they made. […] And the idea that we need to keep sustaining it—well, I’m not convinced that this particular thing we’ve created, this current model, needs to be sustained. It is proving to be unsustainable perhaps because it caters to a few rather than serving the many. […] Maybe it’s time to blow things up, rather than sustain the status quo.

Counting New Beans is an impressive 464 pages long, including the full final research report, four original essays commissioned for this report, and full transcripts of the interviews with artistic leaders and patrons. It is $24.95, and will only be available here, on the Theatre Bay Area website.