On the recommendation of a couple friends who are artists I recently read Dave Hickey’s fantastic 1997 memoir Air Guitar: Essays on Art & Democracy.

As I was reading a couple essays, in particular, I kept thinking about the recent tizzy over the behavior of a pack of celebrities attending the Met gala, who hid out in the bathroom to socialize, take selfies, and smoke.  AJ blogger, Judith Dobrzynski, who commented on the incident in her post, If This Can Happen at the Met and the British Museum … We Have a Big Problem, suggests that the Met is just one (though perhaps an extreme and high profile) example of a growing trend: people who don’t know how to behave in cultural institutions. In her post, Dobrzynski also recounts that the British Museum suffers approximately 50 acts of “pencil graffiti on its ancient sculptures” each year (mostly by schoolchildren).

Her conclusion:

I’ve increasingly noticed the posting of Don’ts, and sometimes Dos, at museums. They do not seem to be enough.

Reading Hickey’s memoir this past week I was suddenly struck by the way arts organizations have set themselves up for this very situation.

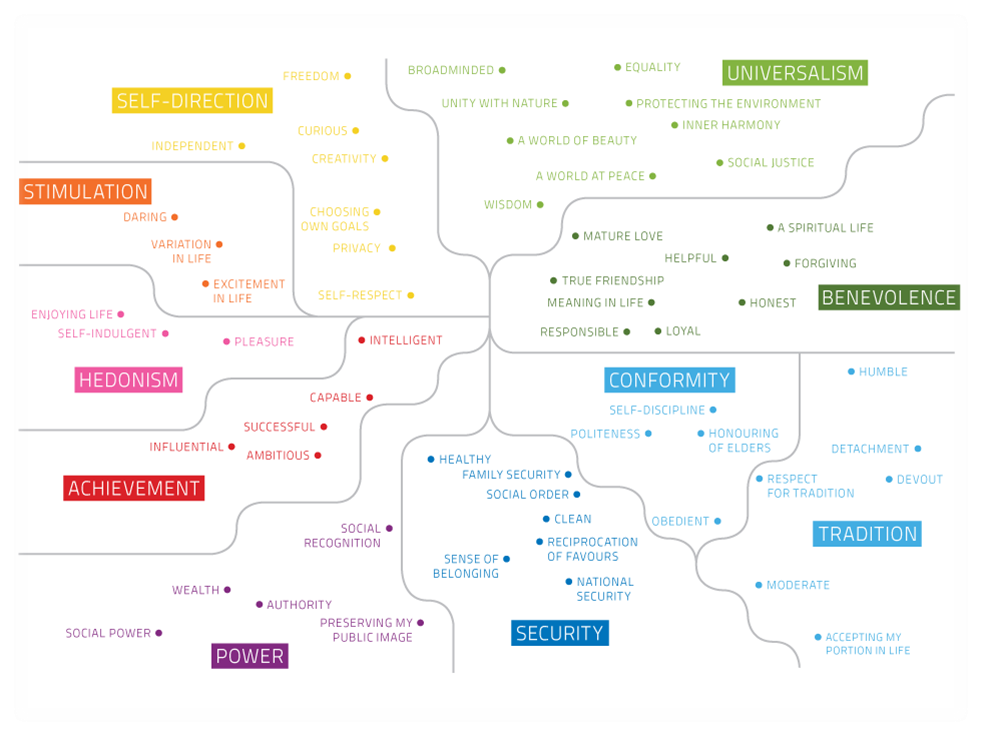

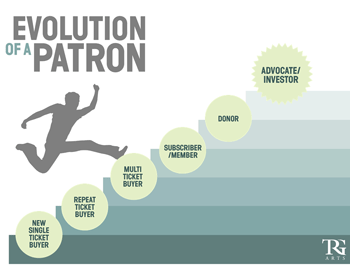

There are a few essays in Hickey’s memoir that I suspect will become lifelong touchstones for me. One is called “Romancing the Looky-Loos.” Looky-loos is Hickey’s dad’s term for those who pay “their dollar at the door” for concerts or art experiences, “but contribute nothing”–spectators, rather than participants. Hickey distinguishes these two types writing, “while spectators must be lured, participants just appear, looking for that new thing.”

Participants show up (no luring necessary) Hickey argues, because they have a “passion for what is going on” and because showing up is a way “to increase the social value of the things you love.” Participants show up for the conversation (both literal and metaphorical). While participants decide what they love and then give it their attention, Hickey says spectators love whatever is the winning side—”the side with the chic building, the gaudy doctorates, and the star-studded cast. They seek out spectacles whose value is confirmed by the normative blessing of institutions and corporations.”

The very next essay in the volume—also a new favorite—is called “The Heresy of Zone Defense.” Among other themes, Hickey riffs on basketball and how it has evolved since 1891 from being a “socially redeeming” activity for recidivist, working-class youth to a sport that is “more joyful, various, and articulate.” That evolution, Hickey argues, is a result of “changing the rules when they threatened[ed] to make the game less beautiful and less visible.” Put another way, the rule changes in basketball over the past century all have been designed to improve the game’s aesthetics.

Hickey contrasts the sort of rules that seek to liberate from those that seek to govern and says that “nearly every style change in fine art has been, in some way, motivated” by the latter. He contrasts the evolution in basketball from that of art, writing:

Thus basketball, which began this century as a pedagogical discipline, concludes it as a much beloved public spectacle, while fine art, which began this century as a much-beloved public spectacle, has ended up where basketball began—in the YMCA or its equivalent—governed rather than liberated by its rules.

Putting the two essays together I’m left with a few thoughts on both the Met smoking-in-the-girls’-room scandal and the more general “problem” (as it is being framed) of people “misbehaving” at cultural institutions:

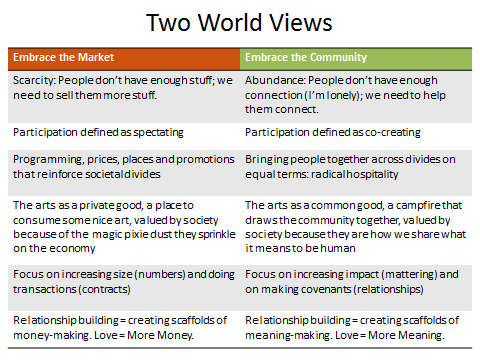

First, if our economic models depend on drawing exponentially more looky-loos than participants then is it really reasonable to expect those lured to our events by aggressive marketing or buzz to be sincerely interested in the arts experience and aware of the rules of the game, so to speak?

Second, while concerns around smoking in the building or drawing on valuable artworks are, indeed, warranted, it strikes me that the big problem is not that people are no longer following museum rules on how to behave. The big problem is that, in response to this situation, museums seem to think the answer is to post more rules–a strategy that has already taken much of the joy out of arts experiences. Of course the celebs that are forced to make a command performance at the Met gala, or risk the wrath of Anna Wintour, rebel in the bathroom. Of course the school kids, confused perhaps because in other areas of life they are encouraged to create and participate, mistakenly draw on the sculptures.

So what’s the solution if, as Dobrzynski suggests, over time an increasing portion of the culture doesn’t seem to get the rules, or seems to grasp them but not to respect them?

Perhaps to find a solution we first need to reframe the problem from a version of “How do we survive in this world that is clearly no longer good enough for us?” to something else. Rather than trying to figure out how to police the culture, perhaps arts institutions could ask themselves:

- Where are we aggressively luring looky-loos rather than inviting participation? and

- Where are our rules seeking to govern artists and participants, rather than liberate them?

And let’s be honest: How many arts organizations actually want or expect meaningful participation from their version of the looky-loos? I’d wager most are lured primarily for the optics and economic gains to the institution.We want to eat our cake and have it, too. We want everyone to show up but we don’t want to widen our conception of what makes for a great arts experience. Inviting everyone and then shoving a long list of rules in their hands is a short-term solution likely to result in many of those people henceforth looking elsewhere for an experience that is participatory, relevant, and joyful–the NBA finals, perhaps.

[contextly_auto_sidebar]

![By Pink Sherbet Photography from USA [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Common](http://www.artsjournal.com/jumper/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Free_coiled_tape_measure_healthy_living_stock_photo_Creative_Commons_3209939998-200x300.jpg)