PostClassic: July 2007 Archives

Tuesday through Saturday of next week, August 7 through 11, the Mark Morris Dance Group will reprise Looky, the dance Mark choreographed to my Disklavier studies, at the summer dance festival at Jacob's Pillow in the town of Becket, in western Massachusetts. Other pieces on the concert employ music by Bach, Brahms, and Stravinsky. Mark's dances are incredibly beautiful, and, as his reputation attests, intimately derived from the music he chooses.

Those of you who do not hold academic positions and wish you did may take some comfort from the following medical statistic. Last December my blood pressure was 145/100; after seven months of absence from the camaraderie of my esteemed colleagues, it is now 107/76.

Richard Fleming is a philosophy professor at Bucknell University, where I used to teach, and thus an old friend. Beneath his cynical sense of humor, he's a wonderfully clear, wonderfully articulate thinker, capable of tracing lines of logic in such a translucent way that even the nonprofessional memory can easily recall them afterward. The philosophy of music is his special passion, and, with composer William Duckworth, Fleming was editor of the books John Cage at Seventy-Five and Sound and Light: La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela, as well as author of several books about Wittgenstein, Cavell, and others. Richard knew both Cage and Leonard Bernstein, and - crazy as this sounds - he used to teach a course comparing their respective Harvard lectures. (Bernstein's set, The Unanswered Question, relies on Chomsky to argue that there is a universal grammar for music; Cage's lectures are randomly written and non-informative.) In short, Richard has an amazing and a surprising mind.

Richard's and my erstwhile common student, Tony DeRitis, who is music department chair at Northeastern University and an incredible character in his own very different way, brought both me and Fleming together last week to teach a group of 19 international students (from Mali, Ireland, India, Brazil, South Africa, and the U.S.) in a program called Fusion Arts Exchange, bringing American music to those of other cultures. Fleming gave the lecture on Cage, and, to end it, told a story, never before in print, that he's kindly given me permission to pass on to you:

Fleming visited Cage late in his life, and asked how he was doing. "Well, I'm just fine," Cage replied, "but all my neighbors in my apartment building are very upset." "Why is that?" "The fire alarm broke last night," Cage explained, "and rang all night. No one would come to fix it, and none of my neighbors got any sleep." "Then why are you all right?," Fleming asked. "Well," replied Cage, "I just lay there and worked the sound of the fire alarm into my thoughts and into my dreams, and I slept just fine."

The story is coming out in a book by Fleming called Evil and Silence: Philosophical Exercses, Socrates to Cage. I'll let you know when it appears; I'll be reading it immediately.

Riffing off of politics again for a moment, I truly hope it is redundant for me to point out that everyone who is worried about the nature of political discourse in this country should be reading Glenn Greenwald over at Salon every day. He is a brilliant researcher and fiercely relentless critic of mainstream media news coverage who has forced some of the worst offenders at Time and the New York Times to modify their rhetoric and admit mistakes. His column today is especially gratifying, as it takes up the use of the epithet "serious," the term that habitual Bush-supporters use these days to distinguish themselves from Democrats and liberal commentators. Dick Cheney and Joe Klein at Time, in this usage, are Very Very Serious because, while they'll take issue with the President here and there, they understand the basic rightness of what he's doing; Nancy Pelosi and Michael Moore aren't serious, because, even though they were right a million times where the Neocons were always wrong, they were never on the Bandwagon to begin with.

The thing I love about it is, of course, that "serious" has also long been the word that High Modernist composers use to distinguish themselves from composers who try to appeal to the audience, who think about accessibility, who are influenced by pop music, who don't build up dramatic climaxes, who appreciate Erik Satie and Virgil Thomson, who don't try to impress each other with the sophistication of their techniques. "Serious" is a condescending but tolerant-seeming word that connotes, well, yes, these postminimalists are composers too, and amateurs may find in them a certain entertainment value, but we must not forget, of course, who the really serious composers are. I've long speculated that, if artists are, as they are called, the "antennae of the race," that trends we hear in music may subsequently filter through the rest of society; and that, since we had a generation of composers who were so in love with their own power within the profession that they didn't feel they had to give a damn about the audience, we now have a generation of politicians so in love with Beltway power that doing good for society no longer even occurs to them. In short, Neocon ideology may be more or less the 12-tone music of politics. By this analogy, of course, the lightening up of music in the last 20 years may presage a similar lightening up and return to sane reality in politics. The analogy may well be totally misplaced, but it does allow me a certain optimism.

This will be the most trivial thing I've ever blogged about - reminds me of those "pet peeves" ranted about by Andy Rooney - but perhaps it will serve as a public service announcement. I'm a technological dunce, but there's one thing I can do better than a large swath of the population: navigate spam filters. I love my spam filter. I activated it a few years ago, and it saves me a good five minutes a day of tedious work. But a lot of people mistakenly think its purpose is to prevent me from hearing from strangers.

If you've never e-mailed me before, and you do so, you receive a message back:

Sorry, I'm so inundated with spam that I have finally had to turn on EarthLink's high-powered spamBlocker. In order for your message to be moved to my Inbox, I need to add your email address to a list of allowed senders, which I'll be happy to do. And if you're already a friend, don't bother responding, because I'll recognize your name and just add it to the list. Don't panic, messages really do get through. If you don't hear from me within 24 hours, it's because I'm carrying on four careers, NOT because your message didn't reach me. Thanks for your patience! KG

I considered this message touchy-feely enough to reassure the most self-loathing and pathetically insecure orphan, but I get the feeling that many people simply read the first sentence and panic anyway. Earthlink then provides a little form to fill out, which takes about ten seconds, which sends a request to me to add someone's name to my "allowed address" list. But as I say in the message, that isn't even really necessary, because every day I check my blocked e-mails to see if someone I want to hear from is trying to get through to me. It takes me a lot less time to do that than it used to to individually select and delete all the Nigerian fortune offers and cheap cialis deals that used to flood my in-box.

Most people seem to work their way through this little labyrinth, but only most. A surprising number decide that repetition is the key. They seem to think that if they keep posting the same message and hitting "send" over and over again, that the cumulative force of all those duplicate messages will burst through my spam blocker and ram its way onto my laptop screen in the middle of a Digital Performer window, or whatever other software I'm working in at the moment. I can't tell you how often I look in my blocked messages and find the same message left six times in quick succession. Others contact people who know me, so that I get messages from friends saying, "I'm forwarding a message that my friend Fred tried to send you, but it was blocked by your spam filter." Others simply give up, and I meet them one day and they say sadly, "I sent you an e-mail once, but your spam filter wouldn't let it go through."

So here's the PSA, which applies not only to me, but to anyone else you're trying to reach: SPAM BLOCKERS ONLY BLOCK SPAM. That's why they're called "spam blockers." If you follow the simple instructions, you are guaranteed to get a message through to the person you're contacting. If you personalize your subject heading, like saying "I'm a fellow composer," or, "Responding to your blog," you'll further increase your chances of being noticed quickly; if your subject heading is "Wow her with three more inches" or "MRS. MBOTU WILLIAMS URGENTLY READ PLEASE," you may indeed get deleted anyway. Of course, I could solve the problem by immediately responding to every e-mail, which would entail giving up my careers as composer, musicologist, professor, and so on, and eventually no one would have any further reason to e-mail me. But in these past few years, only two people (out of thousands) have ever convinced me that they sent me an e-mail that didn't reach me, and misfires of that frequency used to happen even before spam blockers existed.

In any case, I wish that the webmail companies would do a better PR job of telling the public what this highly useful device is all about, and I hope my little notice will contribute to the general education. We return to our regularly scheduled programming.

In case you're having trouble keeping your spirits sufficiently depressed on such a beautiful day, here's a BBC Radio 4 report, and accompanying article, that link Prescott Bush, grandfather of the current White House resident, with the Business Plot of 1933, in which a number of wealthy businessmen tried to convince Major General Smedley Butler to help them lead a coup against FDR, instituting in his place a fascist government allied with Hitler and Mussolini. Apparently the Bush family's interest in turning the U.S. into a fascist nation goes back a long way. (Of course we all knew that Prescott Bush bankrolled the Nazis, but I didn't realize it was based on anything more than financial interests.) Speculation, at the end of the report, is that FDR agreed not to expose the main conspirators in return for them making Wall Street back down and allow his New Deal measures to pass.

A student asks for recommendations for a violin piece (with or without piano) written in the last 15 years. Paul Dresher's Double Ikat is a little too long in the tooth by this point, and I'm having trouble coming up with compelling, more recent examples. So I bring it to you. Personally, I'd be much more interested in something arguably postclassical than in the usual high-modernist glop, but I suppose anything post-1992 would fulfill the assignment.

UPDATE: Please, feel free to recommend your own works. I'm gonna keep talking about my music, go ahead and talk about yours.

[See update below] I've been neglecting PostClassic Radio, because it's been difficult, with all the other work I need to be doing, to justify investing time in an enterprise that might be shut down soon. Here's the message I received from Live 365 this week:

In answer to the top question on broadcasters' minds: we have no plans to shut down on July 15th when the billions in per channel minimums and significantly higher rates come due, unless forced to by SoundExchange.

We believe Congress and the public share our outrage over the fundamental inequity in performance royalty rates. Why is it that terrestrial radio pays NO royalties and satellite and cable radio pay much lower royalties than Internet radio to SoundExchange? Many artists have also contacted us to voice opposition to new CRB rates that will decimate Internet radio and eliminate their chance to be heard. The momentum of public opinion and business sense is on our side and we plan to continue to fight for artists, webcasters and their audiences until a resolution is found.

In the meantime, let us assure you: webcasters covered under the Live365 SoundExchange license will not be responsible for any retroactive fees. Upon resolution of the new rates, Live365 will honor its obligation to provide advance notice of any change in pricing with the option for you to continue services or not, prior to imposition of any increases.

Awhile back, a Washington insider who seemed to know things told me that internet radio would almost certainly squeak through. Today, however, two days before the deadline for massive rate changes, things don't look hopeful, but last-minute negotiations are keeping everyone in suspense; at least, everything is apparently not going to change Sunday as threatened. This next week I'm in Boston, teaching a summer course in American music for international students at Northeastern University. When I get back, if internet radio is still alive, I'll work on a big playlist update.

UPDATE: There's been a reprieve, and internet radio stations are allowed to continue at the old rates until some kind of compromise is worked out. I think the gist is, Nell's still tied to the train track, but Dudley Doright has stopped the train, for now. My Washington informant knew this would happen.

I wonder if other there are other composers who have the same relation to tempo that I do. I sometimes struggle with the beginning of a piece until I get the tempo right. In recent months I've written sketches for a piece commissioned by the Seattle Chamber Players for next January. I wrote a passage at quarter-note = 88. Didn't feel right. Wrote further passages at that tempo. All fell limp the next time I looked at them. Tried a new passage at 112. Even worse. Finally, today, I got an idea at quarter-note = 84 and suddenly wrote 100 seconds of music in an hour. 84 is a good tempo for me, and one I've used before: calm, unhurried, and yet with a little energy. Yet after I've written a piece, I generally give the performer(s) considerable leeway with tempo. In the case of The Day Revisited, though, I learned from experience that the piece only works at half-note = 50, which was the first tempo I'd marked - not a beat more or less.

On the other hand, for my Disklavier pieces I've gotten in the habit of accepting Sibelius's default tempo of quarter-note = 100, and, since there are no performers to worry about, simply used quintuplets or septuplets or 13th-lets or whatever to get the speed I want.

I'll never forget how at the first June in Buffalo festival, 1975, at dinner one night Morton Feldman talked about how young composers used to write everything at 60, but lately they had all started using 72. That was my first inkling that even a tempo could become a cliché. One of the great things about Feldman was that he could pick out clichés no one else would have recognized. I hope 84 isn't becoming a fad.

1. A few years ago, Gloria Coates completed her 13th symphony, and in so doing became the most prolific female symphonist in history, one up on the obscure African-American Julia Perry (1924-79) of Kentucky. Yesterday, Gloria told me she has completed her Symphony No. 15, which ties her with Shostakovich. It will be available on Naxos in a few months. Gloria characteristically does a lot with long, slow string glissandos, often overlaid with tonal passages for a bizarre but gripping effect. I particularly recommend her Symphony No. 4, "Chiaroscuro."

2. Really odd offerings continue to appear on the International Music Score Library Project. A pianist in Kansas has posted Sonatas Nos. 7 and 8 by Johann Nepomuk Hummel. It is enshrined in the literature that Hummel wrote only six piano sonatas, very important and impressive works: the fifth, in F-sharp minor, was considered the most difficult piano work ever written, and Beethoven is supposed to have written his Hammerklavier Sonata in competition with it. Grove Dictionary still lists only six Hummel sonatas, but apparently there are three earlier ones, werke ohne opus, which have been numbered 7, 8, and 9 as coming after his recognized ones - much as the three Bonn sonatas that Beethoven published when he was 12 are enigmatically listed as Nos. 33, 34, and 35 in certain complete editions of the Beethoven sonatas. Very curious. One of my favorite assigments in my "Evolution of the Sonata" class is to give students the first eight measures of Beethoven's first Bonn sonata (without divulging the author) and have them write the remainder of an exposition, to see whether they can do as well as the prepubescent Beethoven did. Perhaps Hummel's early sonatas will work as well.

IMSLP also offers some chamber music scores of the short-lived Hermann Goetz (1840-76), whom Bernard Shaw raved about as one of the greatest of 19th-century composers. I don't quite agree, but I have found Goetz's music as compelling, overall, as, say, Mendelssohn's. And I've also enjoyed the opportunity to look through the two piano concerti (in four movements, like the Brahms No. 2) of the Swedish patriarch Wilhelm Stenhammar (1871-1927). They're not very good. Stenhammar went through a tremendous style change later in life, and, studying Beethoven and Haydn in detail, became a neoclassicist. I am fond of his admittedly extremely conservative String Quartets Nos. 4 through 6, and I hope those will appear in due course. In any case, IMSLP offers an opportunity to study a much richer and more varied 19th century than one learns about in school.

3. I bought a scanner today, and can now upload as PDFs my scores that only exist in the old obsolete Encore notation program. Accordingly, my Desert Sonata is now available on my web site, where it will soon be joined by my early Disklavier studies, as well as Custer and Sitting Bull. I'm inspired to do this partly by IMSLP. My early scores are available from Frog Peak Music, but I love having 13,000 mp3s on my external hard drive, and I'm enjoying having PDF scores there as well. There's something about being able to check out a PDF score online before going to the trouble of obtaining it, and I like giving people a chance to do that with my own music.

4. On a completely unrelated political note: There was a wonderfully telling moment in Sara Taylor's testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee that doesn't seem to have gotten much attention. She started out saying that, as a deputy assistant to the president, she "took an oath. And I take that oath to the president very seriously." Senator Leahy was forced to point out to her that the oath she took was not to the president, but to the Constitution. She conceded her error. Doesn't that just about sum up everything that's been wrong with the Justice Department?

It may be worth noting that John S. Koppel, a civil appellate attorney with the Department of Justice since 1981, has published a satisfyingly scathing indictment of Bush's Department of Justice out west where you might not run across it, in the Denver Post.

Forgive me for not blogging. I have little to say to the world at the moment, and, aside from the heinous political stuff in which you are as expert as I, the world doesn't offer much to attract my attention. I am involved in the little ditzy administrative tasks of getting my music in order, and since I gather that 96 percent of you reading this are composers, you are, or have been, or will soon be, involved in the same species of tasks, and so there is little point in describing them. I acquired a PDF merger (a free one - PDFmergeX), and so am getting all of my multimovement works into single files, which will make them more convenient to download. Mike Maguire and I are redoing the electronic backgrounds to Custer and Sitting Bull, which ought to improve the sound quality immensely. I'm getting new or improved copies of scores printed up, and mailing them off. And I have program notes to write.

This last task is one that almost all composers seem to hate, but that I rather look forward to as a final bit of dessert after the feverish and anxious effort of writing the piece. I love writing about music, and I especially love writing about my own music. I am not, as I suppose I hardly need repeat, one of the predominant "The music should speak for itself!" confraternity to which most composers belong. The music should speak for itself, and I hope it will, eventually. Until then, even the most experienced listeners benefit from a little noodge as to what there is to listen for in a new work, until its style becomes so familiar that many people can hear it for themselves. Relationships that will become obvious on a third hearing may at least be sensed on a first if attention is drawn to them, creating better odds that there will be a third hearing. Nonverbal musicians greatly romanticize "pure" experience, but, except for perhaps the first five years of my life, I don't believe I've ever had a "pure" experience. An artistic culture results not only from perceiving but from discussing what we perceive, putting it into context, comparing it with other experiences. A thousand "pure" experiences, never interpreted, never analyzed, never compared, would lead, it seems to me, to very little. I would not rather be a novelist than a composer, but I have always envied novelists and their world: since words are their medium, no one ever questions the appropriateness of writing about novels, and at great length. I consider music more like the novel in that respect than most people admit. No need to write in and disagree; I take it for granted that I am nearly alone, among composers, in my belief that words have much to contribute in making music digestible and memorable. In fact, perhaps it's not so much that I have little to say to the world at the moment as that I am simply tired of being disagreed with.

In any case, I have written program notes for Sunken City, my piano concerto. I also, since there is scant chance that anyone else would try to perform the piece before its premiere in Amsterdam next October, release a PDF score. (Warning: don't click unless you really want to deal with a 135-page PDF.) These aren't the most literary notes I've ever written, but they explain some important things that happen in the piece, and since I have nothing else to offer at the moment, I offer these:

Sunken City (Concerto for Piano and Winds in Memoriam New Orleans) was a departure for me, whose direction was determined by the medium. Anthony Fiumara asked me for a work for piano and the Orkest de Volharding of Amsterdam. Being an American of postminimalist tendencies, I could have responded with a one-idea piece of continuous textural transformation, which would hardly have been outside my stylistic proclivities. But to write a slowly changing sound continuum for brass, reeds, and piano seems impossible; the piano will barely have space to be heard. The first requirement that imposed itself was that orchestra and piano would have to alternate, which led me to the dramatic shape of a true concerto. I've always wanted to write a piano concerto, but had always thought of strings, woodwinds, drums. I considered the few classical models for piano with brass, and was not impressed. (I am familiar with two wonderful concerti for piano and winds, Stravinsky's and Kevin Volans's; but both employ woodwinds, which I didn't have available.)

The successful model for brass, reeds, and piano that came to mind was 1920s New Orleans jazz. At the same time, I had just been deeply touched by Spike Lee's documentary When the Levees Broke, detailing the tragedy of the government-allowed destruction, and subsequent forced evacuation, of much of New Orleans. (My childhood was dotted with visits to southern Louisiana, where my mother grew up, and some of our oldest friends became Katrina evacuees.) In the documentary, officials from New Orleans visit Amsterdam to see how levees are supposed to be built. So there was my Amsterdam connection, dovetailing with the New Orleans jazz, and I acquiesced to my subject matter as irresistible. The title Sunken City, I thought, might draw a link between Amsterdam and New Orleans - though, hopefully, never with similarly catastrophic connotations.

The first movement is pure fun, the Mardi Gras New Orleans of my imagination, a stylized portrait of the energy level and harmonic language of the 1920s music of Jelly Roll Morton, Louis Armstrong, and Bix Beiderbeck. There are two simple main themes, or perhaps only motives, used in the piece: an alternation of two notes a step apart (sometimes expanded to a third, as in the opening), and a rhythmically irregular repetition of a single note. Only one actual quotation appears in the first movement, a re-voiced chord progression from Frankie Trumbauer's song "Jubilee." Premonitions of the tragedy cloud the coda, which ends in a hasty retreat. The much longer second movement is a kind of interrupted chaconne, based on its opening 17 chords (spelling out the repeated-note theme). Successive variations suggest stages of grief, outrage, nostalgia, and acceptance, but finally the piano drifts into Jelly Roll Morton's "Dead Man Blues" (or rather, its chord changes, with some abstracted bits of the tune), which spreads into the orchestra. The last few minutes return to the chaconne chords, no longer in strict order. The single pitch that runs through all 17 chords is A; the "Dead Man Blues" passages are in B-flat, and the major seventh A above B-flat major provides the movement's rare moments of solace.

The obvious model for a two-movement work with a vastly larger second movement, of course, is Beethoven's Op. 111 (also Mahler's Eighth Symphony). With Beethoven in mind, I had planned to suggest some sort of transcendental acceptance, but as a friend [John Shaw of Utopian Turtletop] reminded me, there can be no acceptance of what happened in New Orleans; not the natural tragedy, which was so foreseeable (and actually didn't happen, since Hurricane Katrina downgraded into merely a level 3 storm before reaching the shore), but the unforgivable political tragedy: the levees never built to last in the first place, the uncaring abandonment of the population to heat, thirst, and death by drowning, the politicized gutting of government agencies meant to respond to disasters, the turning back at gunpoint of honest citizens trying to escape the city by walking over bridges. My friend was right, and the piece ends as it must, in bitter inconclusiveness.

Awhile back my Australian composer friend Andrian Pertout - I should say, one of my multitudinous Australian composer friends - e-mailed me a font for Ben Johnston's microtonal pitch notation. I'm not very good at this kind of technological challenge, and we had been down this road before, so I filed it away to deal with later. But being in between compositions this week and without any particular idea in my head, I tried it out and got it to work! What this means is that now, for the first time, I can notate my microtonal music on the computer with the correct notation. Until now, all my microtonal pieces have had to be hand-written scores, or else with some jerry-rigged notation showing cents sharp or flat, and so on. But I got inspired - or rather, remained uninspired, and thus in need of some mind-numbing busywork project - and renotated my piece The Day Revisited in Ben's beautiful notation. I'm very excited about it.

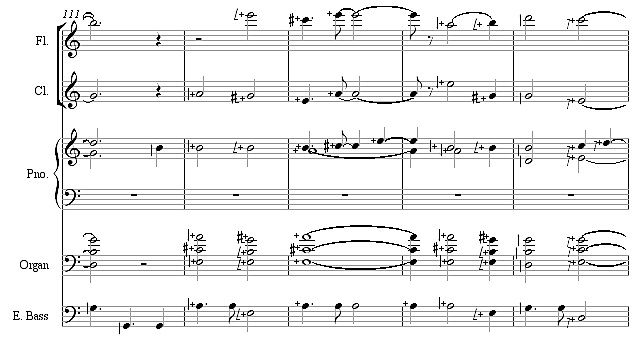

It took me something like 14 hours to place all the accidentals in a 13-minute quintet. You can see a sample here:

And if you want, you can download the entire score here. The little sevens in Ben's notation lower notes to make them 7th harmonics, and the upside-down sevens raise them the same amount. The upward arrows (which I hope you can see at least on the PDF; they're undeniably faint here) raise a pitch a quarter-tone to make it an 11th harmonic, and down-arrows lower the same amount. The pluses correct for the syntonic comma, and if that's Greek to you, well, sonny, you'll understand when you get older. But enough about that. The important thing is that now I have a downloadable copy of The Day Revisited which, even if you don't understand the notation, reveals much more about how the piece works than the old cents-sharp-or-flat score does. And if it took 14 hours, that's a shorter job, and a less exhausting one, than it would have been to copy the score by hand, which I once assayed to do and gave up.

Andrian uses Finale; I use Sibelius. (O when, o when, will these Finale users see the light and bend to the inevitable?) He says the font is more convenient in Finale, where it can be programmed to punch in next to a note like a regular accidental. In Sibelius, I had to treat it like text (apple-T) and painstakingly drag each accidental next to the note. But I'm impressed with the way it looks, at least on my print-out; I'd be curious to hear others' results. He's not quite ready to go public with the font yet. Meanwhile, a recording of The Day Revisited, which will be released in September on my CD Private Dances from New Albion, is still on my web site for now, where you can listen to it here and compare it with the score, if that kind of thing appeals to you. I think, and have been told, that it's my most ear-opening microtonal work yet.

I fantasize that, on my deathbed, someone is going to run in with the news that a new software has been developed that will not only notate Ben's pitch notation with seamless ease, but play it back in incredible acoustic fidelity. Someone like Alex Ross, or Michael Gordon, or one of those guys (they'll all be there) will turn to me and jeer, "Seems you were born at precisely the wrong time, Gann: late enough to find just intonation irresistible, but too early to find it feasible!" The pained expression with which I depart this vale of tears will have nothing to do with my final illness, I assure you.

I'm late with this, having regressed through space and time (lifetime-wise) for a small home-town vacation in Dallas. But every Sunday, wherever I am, I click on the Times music section with a pessimistic sigh expressing the unlikelihood of their ever mentioning any music that might actually interest me. And this week I was encouraged by Daniel J. Wakin's and John Schwartz's article about composer Joseph Bertolozzi, who is writing a piece to be performed, percussively, on the Mid-Hudson Bridge in Poughkeepsie. This looks like the kind of crazy, creative, innovatively public new-music project that composers used to pursue in the halcyon days of the New Music America festival: electronic sounds on the subways, music in the form of a baseball game, singers and instrumentalists drifting on boats, and like that. I'm thrilled to see Mr. Bertolozzi (to refer to him Times-style) pursuing it, and I look forward to driving down to hear his piece. What's less gratifying is that this kind of creativity has so receded from our musical life that the authors treat it as whackily out of the ordinary ("bizarre," "quixotic," actually playing the bridge). Back in the old days, before Reagan somehow made the entire world conservative, using a bridge as a musical instrument - however newsworthy - would have hardly raised eyebrows.

I also failed to bring timely attention to Dennis Bathory-Kitsz's very impressive article in New Music Box about the hyperrealist music of Noah Creshevsky: hyperrealism being defined as "an electroacoustic musical language constructed from sounds that are found in our shared environment, handled in ways that are somehow exaggerated or excessive." Dennis offers us a depth of aesthetic thought, about a very good composer, that we rarely encounter in any medium these days.

Sites To See

AJ Ads

AJ Arts Blog Ads

Now you can reach the most discerning arts blog readers on the internet. Target individual blogs or topics in the ArtsJournal ad network.

Advertise Here

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog