Douglas McLennan: April 2009 Archives

Maybe this is backwards. Who's the more valuable member of your community? The person who gives you money but otherwise doesn't have much to do with you, or the person who buys tickets and shows up for every performance? A thousand dollar donation is the same as $1000 of ticket revenue in the bank. Except it isn't.

Maybe this is backwards. Who's the more valuable member of your community? The person who gives you money but otherwise doesn't have much to do with you, or the person who buys tickets and shows up for every performance? A thousand dollar donation is the same as $1000 of ticket revenue in the bank. Except it isn't. Studies of how people make their cultural choices show that personal recommendations top the list. Most arts organizations try to incentivize donors by giving them perks. Your name in the program, special meet-and-greets with artists, club rooms, even your name in golden letters on the wall of the theatre if you give enough.

What incentives do ticket-buyers get?

A ticket sold isn't just a ticket sold. One audience member isn't the same as another. Communities are hierarchical, and if you can identify the hierarchies and incentivize them you can push people up the ladder. Along the way they'll do things for you (and for themselves). People like to be rewarded for engaging with you.

Sure the performance should be enough reward, I know. But if word-of-mouth is the most powerful way of getting more people into the theatre, how do you promote that word-of-mouth? In online social networks, participation is rewarded for the frequency and quality of that participation, and even small recognitions encourage people to participate at higher levels.

If you have an audience member who brings five friends, find a way to reward them. If they bring 10 friends, give them something more. Every arts organization has a page in their program listing the names of people who contributed money and at what level. How about a page that lists the names of people who brought in more people? Reward them with free tickets to bring in even more. Make them feel like a partner and they'll bring in even more.

The Obama campaign was brilliant at empowering supporters the more they participated. Supporters could sign up for their own page on the Obama website where they could make a personal case for the candidate. They could pledge to raise $1,000 from their friends, then send out emails that directed them to mybarackobama.com to make that personal appeal. It worked brilliantly.

There's another thing. Most organizations don't give people enough ways to support them. Some people can't afford to give money, but they'd be happy to recruit their friends on your behalf. Some people don't have extra time to commit to fundraising or being on your board, but they'd be happy to talk you up. All it takes sometimes is empowering them to do it. And in imaginative ways that don't always cost you money or resources.

Who's making the personal appeal for you? And how are you rewarding them?

Most newspapers have thought of themselves as producers of news. But journalism isn't just writing stories, it's having the news judgment to decide what stories are important and explaining why. Google is a kind of uber-curator of news, somewhat diminishing the important news curation role of traditional editors and reporters.

Most newspapers have thought of themselves as producers of news. But journalism isn't just writing stories, it's having the news judgment to decide what stories are important and explaining why. Google is a kind of uber-curator of news, somewhat diminishing the important news curation role of traditional editors and reporters.More important, it pushes news organizations into the position writers have been in for years. Writers have always been a commodity whose fates have largely been determined by the publications in which they appeared. Because publications did the hiring and deciding what stories were published, they generally had the power in the relationship.

If aggregators assume the gatekeeper role, publications step down a rung, joining writers as producers rather than gatekeepers. This is a significant weakening of traditional publisher power. Publications still compete if they have a strong brand and it still means something to be published in the New York Times or the local newspaper. But even this brand power is being challenged by crowd-rated news services like Digg, which try to qualify and organize stories based on how people rate them.

So news organizations are caught in a wildly expanding consumer marketplace where they offer products (stories) that are only a click away from any of a million other stories. News organizations still have an advantage as brands and they have resources they can throw into coverage. But increasingly, individual writers and small websites can compete more efficiently because they don't have to carry the institutional overhead. Thus a classic example of innovation (the web) subverting a less efficient model (print). Another way of putting it might be that as production and distribution gets cheaper, competition increases.

A similar dynamic might also be playing out in the arts. Traditionally, arts organizations have seen themselves as producers. But they were also

The choice of a single word involved separate deliberations in New York and the Washington bureau and demonstrated the linguistic minefields that journalists navigate every day in the quest to describe the world accurately and fairly. In a polarized atmosphere in which many Americans believe the nation betrayed its most fundamental ideals in the name of fighting terror and others believe extreme measures were necessary to save lives, The Times is displeasing some who think "brutal" is just a timid euphemism for torture and their opponents who think "brutal" is too loaded.At what point is torture to be called torture then? Greg Sargent calls out the Times:

Seriously, why won't the paper use the T-word? Times Washington editor Douglas Jehl told Hoyt that the current administration describes waterboarding as torture, but the Bush administration doesn't. "On what basis should a newspaper render its own verdict, short of charges being filed or a legal judgment rendered?" Jehl asked.

But the bottom line is that by not using the term, the paper is rendering a verdict, too -- in favor of the Bush administration. There's a reason the Bushies don't call waterboarding torture: It happened on their watch, and calling it torture would be an admission of guilt. Naturally, their official position is that they didn't torture. By not describing the acts committed under Bush as "torture," the paper is propping up the Bush argument. Period.

That's the paper's own choice, but it might as well admit it, instead of imagining that there's some kind of middle ground to stake out here.

Some in the audience booed. A few walked out.Before playing the final work on his recital, Karol Szymanowski's "Variations on a Polish Folk Theme," Zimerman sat silently at the piano for a moment, almost began to play, but then turned to the audience. In a quiet but angry voice that did not project well, he indicated that he could no longer play in a country whose military wants to control the whole world.

"Get your hands off of my country," he said. He also made reference to the U.S. military detention camp in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Zimerman has had problems in the United States in recent years. He travels with his own Steinway piano, which he has altered himself. But shortly after 9/11, the instrument was confiscated at JFK Airport when he landed in New York to give a recital at Carnegie Hall. Thinking the glue smelled funny, the TSA decided to take no chances and destroyed the instrument. Since then he has shipped his pianos in parts, which he reassembles by hand after he lands. He also drives the truck himself when he carries his instrument from city to city over land, as he did after playing a recital in Berkeley on Friday.

In the early '00's, the movie industry looked on as the music industry's business model was cannibalized by file sharing services. Bandwidth issues bought Hollywood a few extra years to figure out how to adapt to the digital threat.

In the early '00's, the movie industry looked on as the music industry's business model was cannibalized by file sharing services. Bandwidth issues bought Hollywood a few extra years to figure out how to adapt to the digital threat. Eventually iTunes proved a viable model to sell music over the web, even as the recording industry devolved into smaller pieces. The movie industry did indeed benefit from extra time and no one today is talking about the death of the movie business.

Today journalism is facing devolution of its business model as access to news sources explodes. USC's Robert Niles succinctly outlines the problem:

Which leads to an inevitable question. If large news organizations can no longer support themselves, do we really need large institutions to report news? Niles again:Simply put, while a highly competitive Internet publishing market can provide enough ad and direct payment revenue to support reporting, it can no longer routinely provide the funding to support a traditional corporate model for journalism, one that demands a deep organizational chart and significant annual profits.

That corporate model did provide great value to journalism in the past, of course. Its managers and ad representative leveraged financial support from communities, allowing journalists to do their reporting unconcerned with that work.

Without those payment for those additional bodies, the work of leveraging community financial support falls to the reporters (and few remaining editors) themselves, a task that few are trained to do.

Small organizations can do robust work. Instead of handling all tasks of reporting and editing in house, they can leverage the abilities of their communities to build substantial reporting work. Witness some of the crowd-sourced vetting of Friday "document dumps" done by small sites such as Talking Points Memo, for example. (TPM Media grew from a one-person blog, by the way.) Small and one-person news sites can work with one another, as well, to build and share traffic and reporting resources. Large-scale investigative reporting need not be sacrificed under a new, small-scale organizational model.There's lots of debating to be done about whether we need large institutions to report news. But a similar question can also be asked about the arts. The 1990s was a decade of arts institutionalization in America. Smaller theatres became larger theatres. Mid-size museums became bigger museums. And symphony orchestras expanded their activities.

The internet has decentralized the arts. People make art online, compose and record music and make movies in home studios, Massive online multiplayer games have changed the ways we think about narrative. Personal digital players have changed the ways audiences consume art.

Concurrently, the institutional arts are finding their business models eroding as corporate funding dissolves, foundation support erodes and endowments shrink. Perhaps things will bounce back when the economy improves. But maybe not. We increasingly distrust the institutional voice in favor of individual or community collaboration, and whereas we once needed institutions to accomplish things, increasingly we find community effort to be more efficient. Clay Shirky has been exploring this idea for a while:

Surely we need institutions to perform symphonies, display Tutankhamun relics, or dance Swan Lake. But defenders of news organizations say the same thing about the need for newspapers to do in-depth reporting. Then ProPublica and Politico and GlobalPost come along with ways to fund such reporting.

One could imagine something like the "community of musicians" orchestra exec Ernest Fleischmann and New Criterion writer Samuel Lipman debated about some 20 years ago as a way to perform orchestral music. Theatre is already largely a freelance profession for actors, and one could imagine regional theatres as homes to many producer/productions rather than the single-tenant creatures they are now.

And there's something else. As people have more choices, their loyalties to institutions soften. Most arts institutions have done a better job of selling tickets than building communities. In a world of rapidly expanding choice, selling tickets gets harder. For an audience, investing in a relationship or community is different from the consumer choice of simply buying a ticket. If you are primarily a consumer choice, you are increasingly at a disadvantage as the choices expand.

Arts organizations that focus on "selling more tickets" will more and more lose out to community-based networks and companies that figure out that community experience beats consumer transaction. What if institutions aren't the best way of making art?

There is no shortage of people who seem to have figured out what's ailing journalism. There seems to be an even bigger number of people who have ideas about how to fix it. What seems to be missing is the Steve Jobs who has the ability to marry the analysis of the problem with the creativity of a solution and the sustainability of business model to support it.

...women playwrights are vastly underrepresented on our stages. Because "diversity" isn't just a buzzword. The Pulitzer isn't important in itself; it matters because of its ripple effect. Quite simply, winners and finalists get noticed. They get produced. The Pulitzer changes the composition of our canon, the stories we as a culture tell ourselves. Women's voices need to be a much more significant part of that.Second - I've been in LA this week talking to critics gathered here for the NEA Arts Journalism Institute in Theatre and Musical Theatre. We've been discussing the role and boundaries of arts journalism and what constitutes the new journalism. Is it journalism when a theatre or dance company produces its own video interviews? It's difficult sorting out the role of the critic when everyone seems to be setting up shop as a journalist of one sort or another. So a recent dustup between a Toronto radio host and actor Billy Bob Thornton during an interview got me to thinking about how we define "real" journalism.

If there's an expectation that star interviews aren't real journalism, then where's the line where "real" journalism begins? So coverage of Universal is compromised by pre-set conditions. What about coverage of the LA Philharmonic? Billy Bob gets to say what he won't talk about ahead of time. Does Stephen Sondheim get the same treatment? Renee Fleming?

Maybe we should blame the invention of the TV remote control: people often do. At some point around 30 years ago, it became possible to hop aimlessly between channels. Programme-makers became convinced that they had to make a pitch for their show in its opening few seconds, and then keep on pitching just to keep the audience on side. But why has this requirement to grab, grip, deliver a punch (the language is nearly always that of physical violence) infected nearly every other medium? After all, you've already chosen to buy that novel, or theatre ticket; the chances are you're going to stick at it even if the story moves slowly, if it rambles or pauses to digress. But more and more, it seems, we treat every audience as though they carry a phantom remote control. We are terrified of losing them.

aims to supply publishers with ready-made tools to charge Internet fees, an idea that has gained currency as advertising revenue plummets, but whose prospects of success are doubted by many media analysts. The company, which says it may have a product ready by the fall, says the advantages are that publishers would not have to develop their own systems and readers could use a single system for many different publications.Essentially, it's a pass that readers would buy that would give them access to content orgs would put behind pay walls. Brill has been out trying to sell the idea but some critics are skeptical. I can't see how the numbers work out in such a plan. To sign up enough news organizations to attract the tens of millions of readers it would take to make such a pass pay for lost traffic and ad revenue makes it unlikely.

But let's assume for the moment that JournalismOnline could get enough newspapers to sign on and develop a large user base to generate significant revenue. I still think it's too late. In the past couple of days, as I've talked to colleagues, I've been surprised that we all seem to be in agreement on this one. This is a deeply flawed idea that would only hasten the demise of traditional news organizations. The web now offers so many sources for news and opinion, that even though the traditional press is still the primary source for original reporting, it's far from the only one. Throwing up walls around content will only make the new media sources stronger and provide them with more resources.

Yes, most of the good reporting is still in the traditional press. But that's because the traditional press was the way such reporting was supported. That business model is falling away now, and newer news ventures are more nimble at adapting. So rather than help the cause of newspapers, JournalismOnline is likely to hurt it.

This is hardly scientific, but Markos Moulitsas at The Daily Kos decided to see which sources his site drew upon in a one week period.

While newspapers were the most common source of information, they accounted for just 123 out of 628 total original information sources, or just shy of 20 percent. And a huge chunk of that, up to half, came from links in the Abbreviated Pundit Roundup, which is specifically designed to track what some of the nation's top pundits are yammering about. In the unlikely and tragic event that every single newspaper went out of business today, we'd have little problem replacing them as a source of information. Even most of the pundits we're following would stick around somewhere or other. It's not as if Paul Krugman's fate is intertwined in any way with the NY Times'.

I think that many of us who have loved newspapers and are lamenting the demise of arts coverage in them are sad more about the loss of what we thought newspaper arts journalism could be rather than the reality of the typical coverage most often practiced in recent decades. The failures of arts journalism are many. Traditional arts journalism did a lousy job at covering dance. It never figured out how to cover community culture very well. It so often pandered to a view of the arts as institutional rather than artist-driven. And it too often pontificated rather than explained.

I think that many of us who have loved newspapers and are lamenting the demise of arts coverage in them are sad more about the loss of what we thought newspaper arts journalism could be rather than the reality of the typical coverage most often practiced in recent decades. The failures of arts journalism are many. Traditional arts journalism did a lousy job at covering dance. It never figured out how to cover community culture very well. It so often pandered to a view of the arts as institutional rather than artist-driven. And it too often pontificated rather than explained. Ah, but when it was done well, it was revelatory. Mark Swed taking us inside the head of John Adams to see Doctor Atomic. Ada Louise Huxtable explaining how buildings create a sense of history that never was. Bob Christgau cutting through the hype to get to the center. I could go on and on.

It's easy to think of the decline of newspaper arts journalism as the death of arts journalism. The familiar argument is that the professional critics do their work there and if the there disappears, so will the journalism. Somebody's got to pay the critics. But the reason the critics were at newspapers was because that's the place that supported them. As something else rises to take their place, the critics will go there.

I've recently come to feel that the new thing (whatever that is) won't have a chance until the old order is disposed of. Newspapers are sucking up all the oxygen in the room, and the startups won't have room to flourish until newspapers get out of the way. I say this with the greatest respect. I love newspapers, but the business decisions that have dominated in recent years have eroded some important journalistic values (the whole he said/she said fetish, the uncritical "objectivity" trope, the info-tainment tangent) and the failure to adapt to the expectations of a newly empowered media-savvy audience has been fatal. There isn't yet an established new business model to support arts journalism, but there won't be until the old competition has done its dead cat bounce.

In the past few months new journalism startups have been proliferating. Every day new projects are being announced, and many models are being tried. Even a year ago it was difficult to get the arts community to pay attention to the erosion of traditional arts journalism. Now cultural leaders across the country are talking to one another and trying to imagine what comes next.

So the wane of traditional arts journalism is actually a creative destruction that will lead to something better. Hopefully much better. Commenters on the NPR arts journalism piece notwithstanding:

I have an MFA and 30 years behind me actually making art vs. criticizing it. Artists - whether a composer or a playwright or a filmmaker have known this for YEARS and have discussed it and made movies and literature about it even. Good riddance to all of you critics who have had nice jobs and health insurance policies spewing your supposed expertise in your easy chair while the art community struggles to even eat. We don't need you - we never did.

People want things how they want them. In Japan, "five of last year's top ten best-selling novels started life as mobile phone - or keitai - novels."

There was a time when mobile phones were used simply to communicate. In high-speed Japan, where more than 100 million people own mobile phones, they are not only a platform for novelists, but for all forms of artistic expression.

The last time I redesigned ArtsJournal, I discovered that only about 25 percent of those using AJ

ever came to the website. Some users weren't even aware that there was a website. They get it through newsletters, rss feeds, widgets, Facebook and now Twitter. I realized that I had been thinking of AJ as a website. That means I wasn't thinking about 75 percent of our users. Or designing content for them.

Twitter novels or SMS stories might not seem like literature. Video games might not seem like the hot new literature. But at their heart, they're stories, even if delivered in unfamiliar form. The lesson then, I think, is that if you think that your product is a piece of paper somebody holds in their hands, you're going to be left behind. Or, at the risk of dumping on an already belaguered industry: The car is only a means to get some place. What's important is what happens when you get there.

Star lifestyle writer Jim Auchmutey will be leaving. So will star war correspondent Moni Basu -- perhaps not surprising since the AJC's days of sending reporters abroad seems to be over. The paper also appears to be clearing house of its arts critics: visual arts critic Cathy Fox, theater critic Wendell Brock and classical music critic Pierre Ruhe, as well as Sonia Murray, who writes about the hip-hop scene.

All generally accepted truths notwithstanding, more than 96 percent of newspaper reading is still done in the print editions, and the online share of the newspaper audience attention is only a bit more than 3 percent. That's my conclusion after I got out my spreadsheets and calculator out again to check the math behind the assumption that the audience for news has shifted from print to the Web in a big way.

Much of the big shift in our culture right now is a re-ordering of power. For the past 50 years, mass culture, fueled by TV, has been a dominant power. When success is measured in millions of eyeballs (or ears), quality is a secondary commodity. Mass culture has permeated the ways we think about all culture.

Power in the mass culture model is controlled by gatekeepers - the TV networks, radio stations, record producers, publishers. They had power because they could afford expensive cameras and studios and recording equipment essential to making things and getting them to an audience. Some of the "talent" - the musicians, actors, writers, journalists - did very well in this model if their work found a huge audience. The vast majority of musicians, actors, writers, and journalists did considerably less well.

The mass culture model only works when the means of creation and distribution are limited in some way - a small number of TV channels available, for example. One could think of the record companies or the TV networks as middlemen who were essential for an artist to connect with a large audience.

But the online world has largely been a revolution of plenty. Now anyone can make studio-quality recordings, professional-looking books or movies or radio shows. So goodbye to the middleman, right?

Nick Carr says not:

For much of the first decade of the Web's existence, we were told that the Web, by efficiently connecting buyer and seller, or provider and user, would destroy middlemen. Middlemen were friction, and the Web was a friction-removing machine.

We were misinformed. The Web didn't kill mediators. It made them stronger. The way a company makes big money on the Web is by skimming little bits of money off a huge number of transactions, with each click counting as a transaction. (Think trillions of transactions.) The reality of the web is hypermediation, and Google, with its search and search-ad monopolies, is the largest hypermediator.

So the web did away with old gatekeepers and is replacing them with new ones. Gatekeepers have always had power over people who make things. Carr writes that:

When a middleman controls a market, the supplier has no real choice but to work with the middleman - even if the middleman makes it impossible for the supplier to make money. Given the choice, most people will choose to die of a slow wasting disease rather than to have their head blown off with a bazooka. But that doesn't mean that dying of a slow wasting disease is pleasant.

So who are the mediators/gatekeepers/middlemen in the arts? At the most basic level, they're the artistic directors and a system of talent scouts and producers who build careers. Some of this power has waned in recent decades. Gone are the days when a Sol Hurok could make a star or a Tchaikovsky Piano Competition winner have an instant career.

Critics at newspapers, the most powerful of whom legendarily could "close a show" with a bad review also wielded great power. But with arts coverage falling off the pages of the local press and the local press falling off the edge of who knows what, critics are not the gatekeepers they once were even if they're still around.

Now artists can produce their own work and often distribute and promote it better than the old channels could. But one can imagine so many voices braying for attention that just being able to make and get one's art out to an audience doesn't mean that there's an audience interested in it.

So it's back to the middlemen. Right now, it's unclear who or what are going to emerge as the new mediators in the arts. We have access to too much stuff for it to make sense, and no media has grown to dominate the middleman function in the new arts economy. So far everyone's making do with their own ways of dealing with information overload.

Once, an arts organization that could hype its shows and sell tickets

online might have an advantage in the marketplace. Now there's no advantage

because everyone does it. It was a novelty for a theatre to be on Facebook or a dance company to have its own YouTube channel. No longer.

Slowly we're beginning to see familiar behavior reassert itself. We're told that social networking sites such as Second Life and MySpace are dying as Facebook and Twitter grow, perhaps because some people who have established their online communities want to be able to have fresh starts online the way they do in real life.

If people trade off their online communities are they also becoming less loyal to their offline communities? If we assume that there is still a need for middlemen and that the old middlemen are falling away, what's going to replace them? And where does the new arts organization position itself, with technology and without it?

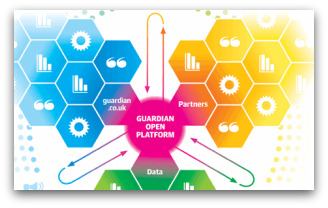

At a time when the American newspaper industry increasingly considers ways to lock down its content and put it behind pay walls, the ever-innovative Guardian newspaper is flinging wide its gates and making it easier for others to take and use its content. Last month the paper announced something it's calling "Open Platform", which is a set of tools that allows anyone to build applications to pull Guardian content and re-use it on the internet.

The Guardian Content API includes articles as far back as 1999 and in some cases much further back. There are approximately 1,000,000 articles available. We will continue to open up more content as we're able to.

One of the most powerful things open-source software developers have discovered is that if you open up your toolbox to anyone who wants to use it and allow them the ability to tinker and create, they'll build things with it you never could have imagined. Drupal, for example, is a powerful free open-source content platform that has hundreds of innovations built into and on top of it because users are encouraged to take Drupal for free and make new things with it. Apple has unleashed a torrent of creativity with its iPhone Apps store.

Already, developers have started building applications with the Guardian's Open Platform. Some examples:

"I decided to write an application that searches The Guardian's archive and returns a link to the top hit using Twitter as the UI and the message bus. I didn't need to build a new web site or client application. I wanted people to use whatever technologies they prefer most."

Or this:

"Towards the end of last week, a sleepness night led me to indulge a childish sense of humour with 15 minutes of tomfoolery, the output of which was a graph comparing the decline and fall of various swear-words in the pages of the Guardian over the last decade. In a bid to retain some sense of self-respect, I'll for now ignore the fact that this graph has achieved a readership that dwarfs anything else I've written in my career to date, and focus instead on how I did it."

Who knows what readers will create? But the bigger point is that once the Guardian's users are invited in and given the power to make their own things, they form a stronger community around what the Guardian does. Is there a business model in that? Yes, just as eBay created a new generation of online entrepreneurs, the news organization that helps its community be entrepreneurial stands to reap rewards.

When people ask me which is the news organization that most "gets" the internet, I usually mention The Guardian. The paper has an outsized online presence compared to its print circulation, and it has consistently led the pack in thinking about developing an audience and gathering and presenting information. The Guardian has a huge American audience, and its cultural coverage is probably the best around. In a related post on ARTicles today, I write about the Guardian's artist-in-residence program and some of the reader reaction.

Hot on the heels of AP saying it will go after news aggregators:

A country radio station in Tennessee, WTNQ-FM, received a cease-and-desist letter warning from an A.P. vice president of affiliate relations for posting videos from the A.P.'s official Youtube channel on its Website. You cannot make this stuff up.

You cannot make this stuff up. Forget for a moment that WTNQ is itself an A.P. affiliate and that the A.P. shouldn't be harassing its own members. Apparently, nobody told the A.P. executive that the august news organization even has a YouTube channel which the A.P. itself controls, and that someone at the A.P. decided that it is probably a good idea to turn on the video embedding function on so that its videos can spread virally across the Web, along with the ads in the videos.

While the recession might be hard on some publishers, the romance novel genre is booming, reports the NYT.

Harlequin Enterprises, the queen of the romance world, reported that fourth-quarter earnings were up 32 percent over the same period a year earlier, and Donna Hayes, Harlequin's chief executive, said that sales in the first quarter of this year remained very strong. While sales of adult fiction overall were basically flat last year, according to Nielsen Bookscan, which tracks about 70 percent of retail sales, the romance category was up 7 percent after holding fairly steady for the previous four years.

What the story doesn't say, is that eHarlequin, Harlequin's website, is one of the best-thought-out commercial social networking sites on the net. It turns out that a significant

number of romance novel readers believe that they too could write a trashy book. Rather than just treating these people just as book buyers, Harlequin built a community around them and turned eHarlequin into the go-to site for romance novels.

There you can meet Harlequin's editors and see what they're looking for. You can meet other readers, have your writing critiqued, learn how to write compelling characters, about plot development, network with fans, meet and chat with your favorite writers. You can't be interested in this genre and not go to this site.

eHarlequin isn't just interactive in that its staff responds to readers, it takes the interaction steps further by making it possible for readers to meet and interact with one another. This is where people make friends. This is where talk about things that are of interest to them. Instead of just producing a lot of content for the site, Harlequin relies on the community to

create much of it. eHarlequin is less a producer of online content than it is a facilitator of social interaction.

So what? The so what is that Harlequin has turned consumers into community, one that builds and strengthens an audience for the company's books. Harlequin isn't just a consumer choice for these people, it's something they're a part of and that they have loyalty to. They're ambassadors for it.

Contrast eHarlequin to the way most arts groups market. Their websites are little more than electronic brochures. They sell tickets in an increasingly crowded marketplace as a commodity rather than a lifestyle choice. They think of audience members as interchangeable; a ticket sold is a ticket sold.

In fact, a ticket sold is not just a ticket sold. Successful web companies today think of themselves less as producers of content than facilitators of community. The definition of success in the new web economy is not in attracting eyes for content, but in getting the people behind those eyes to create something in response. If they do, they'll surely be back. If they do, they'll bring other people back with them. If they do, they'll expand the base that supports the community.

Nothing new here. Amway, Mary Kay, mega-churches, and more recently the Obama campaign have understood the power of building communities around you. Harlequin understands that if it can build and energize a community, it has expanded its market. And (and this is no small thing), by being part of the community itself, Harlequin comes to understand its audience better and gets to see what matter to them. This is market research gold.

The new $1.5 billion Yankee Stadium is lavish in every way:

Each locker is equipped with a computer that will deliver scheduling and practice notes as well as an Internet connection. Players will enjoy a chef to cook them breakfast along with world-class whirlpools and training equipment.

Not least of all the ticket prices:

Premium Legends Suites seats, those closest to home plate, were priced from $500-$2,500 as part of season-ticket packages when the team began selling them in 2008. Some of the seats remain available for single games, with the price rising to $2,625, according to the team's Web site.Makes even these high-end opera tickets seem cheap by comparison, no?

Lots of arts organizations have blogs on their websites. Most aren't very good, and they're difficult to maintain well. There are many out-of-work critics. And less and less arts coverage in local press. So why not critics-in-residence?

Yeah independence. But let's suspend for a moment the idea that criticism's highest calling is simply to inform consumer choice. If instead the idea is to promote informed and interesting commentary, then who has more of an interest in this than artists and arts organizations? If readers knew that a critic was in residence rather than being paid by a local news organization, they might read the commentary differently, but so what? Would you rather read PR boilerplate that nobody believes or the observations of someone trying to engage with the art, even if they're paid to do so by the institution?

Our ability to judge news sources is much more sophisticated now that it used to be. There is value in a Yelp or Amazon review even if it's not vetted. If the critic in residence was clearly labeled as such, the conflict is transparent and readers could make up their own minds.

There are critics in the traditional press who pander. A critic in residence who pandered wouldn't have much following. But what kind of statement would it make for an arts organization to invite a critic to be really critical and help spread that criticism? Maybe a festival with a beginning and end would be a good testing ground.

Of course there are big ethical issues. But art critics already write catalog essays for museums. Music critics write program notes. Newspapers take ads from arts organizations. Rules have been developed to define the ethics of each situation. Why couldn't there be a critic-in-residence protocol that helped promote intelligent discourse and didn't compromise the reader, the critic or the institution?

I'm not arguing that critics inside arts organizations (hmnnn... embedded critics?) is any kind of substitute for the Times review or NYRB essay. But the definitions, forms and conventions of journalism are being prodded, poked and reconsidered, and the idea maybe deserves some consideration before being dismissed. Currently there's no ethical standard for artsbloggers, yet some bloggers have big influence. If there were standards, who would set them?

While I'm on the topic of institutions criticizing themselves in public, I've always loved The Stranger's long-running Public Editor column, which trashes the contents of each week's issue. Not only is it fun reading, but it declares that The Stranger doesn't take itself too seriously.

"We always tried to design each new protocol to be both useful in its own right and a building block available to others. We did not think of protocols as finished products, and we deliberately exposed the internal architecture to make it easy for others to gain a foothold. This was the antithesis of the attitude of the old telephone networks, which actively discouraged any additions or uses they had not sanctioned." - Stephen Crocker, explaining how early net standards were developed and adopted.

Are the arts the telephone companies or the internet pioneers?

I gotta admit - sometimes it's days between times that I check my voice mail. I resent how cumbersome vm is. Way more cumbersome than texting or email.

Looks like my voicemail tardiness is common:When it was introduced in the early 1980s, voice mail was hailed as a miracle invention -- a boon to office productivity and a godsend to busy households. Hollywood screenwriters incorporated it into plotlines: Distraught heroine comes home, sees blinking red light, listens as desperate suitor begs for another chance to make it all right. Beep!

But in an age of instant information gratification, the burden of having to hit the playback button -- or worse, dial in to a mailbox and enter a pass code -- and sit through "ums" and "ahs" can seem too much to bear.

Research shows that people take longer to reply to voice messages than other types of communication. Data from uReach Technologies, which operates the voice messaging systems of Verizon Wireless and other cellphone carriers, shows that over 30 percent of voice messages linger unheard for three days or longer and that more than 20 percent of people with messages in their mailboxes "rarely even dial in" to check them

| The Colbert Report | Mon - Thurs 11:30pm / 10:30c | |||

| The 10.31 Project | ||||

| ||||

Beck is a hysteric, but he's getting huge ratings. He's actually beating every other cable news show except the long-established Sean Hannity and Bill O'Reilly. This after only a few months on the air:

CNN has slipped into third place behind Fox and MSNBC.

Lessons? The obvious: Whackadoodle sells. Outrageousness sells. Dogma sells. Entertainment sells. But I wonder if there's something else. It's been a long time since cable news has been about real news. It's become a kind of sprawling news-o-tainment "reality" show in which the goal is to stir people up rather than inform them.

This isn't an argument against such shows. If people want to watch them, fine. Rather, I want to focus on CNN. CNN was the first cable news channel and it started out focusing on traditional news. Then Fox News launched and had success with its news-o-tainment format. CNN responded by trying to throw in a bit more pizzazz, Not, unfortunately for CNN, as entertainingly as Fox, and its ratings have been slipping ever since.

So CNN is a mess. Almost unwatchable as a purely news channel (with Wolf Blitzer's constant hyping of "the best political team on television") and a steady diet of inanities and blow-dried dumb anchors, it also doesn't deliver much as entertainment. It can't match Fox at stirring up the outrage.

CNN's predicament reminds me of that of many local newspapers. Newspapers perceived that the serious stuff didn't have a big enough audience so they tried to pop-culture-up and make the stories, ideas and language simple. Fox works because it blatantly hammers out its agendas while CNN's agendas are watered down out of some vestigial sense of traditional journalism. CNN doesn't play Fox's game very well - instead it half-plays the Fox game and consequently doesn't do either news or news-o-tainment very well. There's a parallel for newspapers. Rather than attract a hipper younger audience, they alienated their core readers and failed to get the kids as well.

In our increasingly nichefying world, using mass-culture strategies to get bigger audiences works against you. A proliferation of sources means that people can be pickier to get exactly what they want, and general bland multi-purpose content has less and less appeal. A lesson for anyone competing for an audience these days.

AP says it will "take action" against web aggregators that don't pay fees for linking to AP stories.

Taking aim at the way news is spread across the Internet, The Associated Press said on Monday that it will demand that Web sites obtain permission to use the work of The A.P. or its member newspapers, and share revenue with the news organizations, and that it will take legal action those that do not.

Associated Press executives said the policy was aimed at major search engines like Google, Yahoo and their competitors, and also at news aggregators like the Huffington Post, as well as companies that sell packaged news services. They said they do not want to stop the appearance of articles around the Web, but to exercise some control over it and to profit from it. The A.P. also said it is developing a system to track news articles online and determine whether they were used legally.

Okay, I realize I have a self interest here. ArtsJournal is built on aggregating stories and sending readers after them. And I realize the newspaper industry is under siege and that AP is suffering. The news industry's woes have spawned a number of increasingly desperate please for solutions, the most common of which seems to be that readers are going to have to start paying for content because it costs us to produce it and they just have to. That's not an argument, it's cry of desperation, and there's so far no evidence that readers will so pay because they want to.

But if you want to understand why the news industry has so failed at adapting to the web, this latest threat by AP is a good example. Google is the enemy? Actually, Google send more traffic to most websites than any other source. Publishers clamor for Google attention. A whole industry has grown up around optimizing web pages to attract Google. Google can throw so much attention to a news story that it can swamp your server. This is bad?

According to the AP, yes. But the AP argument is wishful thinking and not just a little bit disingenuous. If publishers (or AP) didn't want Google crawling its pages and aggregating links, there's a way technically to make those pages invisible to Google. So this isn't s legal argument, it's a technical one. What AP seems to be saying is "please aggregate us, but because you're so good at it we want you to pay us." Trouble is, since AP and the publishers have allowed Google unfettered access, and indeed encouraged the search engines to discover their content, they wouldn't seem to have much of a case arguing that Google is "stealing" from them.

And other aggregators? The web is all about pointing users to content. This blog entry is based on a story found in the New York Times. Does that mean I should be paying the Times for writing about their story? Fair use would seem to protect me.

And ArtsJournal? I believe we offer a valuable service in curating stories about the arts. Our little headlines and excerpts are intended to throw traffic at stories that might not otherwise get a lot of attention. Without us, fewer readers will see those stories. Editors pitch us to link stories every day. So this is stealing? If we had to pay to link to news publications such as the Times, we'd stop linking to them and we'd concentrate on finding other content. And this is the real problem for the traditional press. When they were the only sources, they could dictate the terms. The proliferation of other content has diminished their power, and walling themselves off from the rest of the web will only hasten their downward business spiral.

One last point. I will say that it does seem to me that sites like Huffington have been crossing a line in recent months. Their excerpts are now often so long that there's no reason to click the link to see the original story. This does seem like they're appropriating stories in a way that offers no benefit to the source. As a daily user of the site, I find the long excerpts annoying (I'd prefer to see the complete original).

I understand HufPo wants to inflate its page views. In the long run though, I think this policy damages them - from the reader side, it forces extra navigation to get to the sources, and from the publisher side it cuts down the amount of traffic HufgfPo could send.

Often when people talk about using technology, what they're really talking about is platforms. A blog is a platform. A Facebook page is a platform. A YouTube channel is a platform. They aren't technology strategies. Platforms are constantly changing, and if you're locked into one, it's difficult to keep up when the next one comes along. A smart technology strategy isn't dependent on a platform, but absorbs new them as they come along. So how do you deal with this development?

who cares deeply about his job and how he covered the orchestra, an orchestra that grew increasingly unhappy with Rosenberg's opinions and punished him in little but meaningful ways, and a newspaper caught in the middle and forced to think about the way it wanted to cover one of America's great cultural institutions. It's compelling reading, and near the end of the piece the orchestra's lawyer betrays some of the rancor, as he talks about Rosenberg's lawsuit:

who cares deeply about his job and how he covered the orchestra, an orchestra that grew increasingly unhappy with Rosenberg's opinions and punished him in little but meaningful ways, and a newspaper caught in the middle and forced to think about the way it wanted to cover one of America's great cultural institutions. It's compelling reading, and near the end of the piece the orchestra's lawyer betrays some of the rancor, as he talks about Rosenberg's lawsuit:"The hypocrisy of a music critic challenging the right of other people to respond to his criticism is based upon the arrogance of modern media in general," he says. "That they believe they actually own the First Amendment and it belongs to them. And they believe it's their right. It isn't opinion. It's gospel. Like they carried it down on a tablet from the mountain."

He says the orchestra administration had every right to complain about Rosenberg. He says reading other critics provides the perfect defense to their complaints.

"It wasn't just the people from the Cleveland Orchestra that responded to Don Rosenberg," he says. "Every time the Cleveland Orchestra got a rave review in New York or Chicago or San Francisco or Vienna or London or Paris, it stood there in stark contrast to the often angry and harshly critical reviews of Rosenberg."

Duvin says he doesn't question Rosenberg's free speech, and he can't believe Rosenberg would call the orchestra's free speech into question.

"He has a right to that opinion. But he doesn't have the right for others not to have an opinion on him. And he doesn't have a right to be the sole critic for the hometown paper of the Cleveland Orchestra."

Back in January I finally canceled my subscription to the daily newspaper. Tough (and symbolic) thing to do. I've always subscribed to the local paper. My paper had become thinner and thinner as the stories I used to buy it for drained away with cuts in space and staff. Many of the stories were now being written by interns.

I'm an online guy, and I get most of my news online. Still, it seemed important to support the local newspaper. Even when the width of the paper was trimmed to about the size of a tab. Holding it in my hands just seemed... wrong.

So when Hearst announced it was going to close the Seattle Post-Intelligencer if it couldn't find a buyer in 60 days, I decided I would leave the P-I before it left me (I never did like being the one who was left). When I called to cancel, they offered me a steep discount - half off. I said no, and for good measure, told them it was because they had cut so much of their arts coverage.

A week later, someone from the Times/P-I circulation department called with an even better deal. For only a couple dollars a week, I could be restarted. They didn't want to lose me. I said no, and repeated my line about the loss of stories I liked and the shrinking of the paper. "Yes, but it's only a couple bucks a week!" the guy said. Yeah, said I, but that doesn't matter if what I wanted was no longer there.

A couple of months later the P-I closed. The rival Times, which ran the joint subscription business side of the operation automatically transferred former P-I subscribers to Times clients. This week I've had two calls from the Times. First, they wanted to "reward" me for being a "loyal" subscriber by giving me a free subscription. No, I said.

The next day someone else called to offer me a subscription for 24 cents a week. That's only $10 a year! exclaimed the agent. How could I pass that up? Pretty easily, I said, to his professed astonishment. Only $10!

"So cheap they can't give it away." An expression my dad used to use from time to time. Now I understand. Maybe it's churlish not to support the local papers by subscribing. But I'm surprised by how offended I am at the way they have run their businesses. By how they have offered less and less. By how they have repeatedly insulted the intelligence of the readers who cared about them. I'm sorry the P-I is gone. But now it's time to move on.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog

Recent Comments