Inspired by work and writings of John Cage and Rebecca Solnit

How do you calculate upon the unforeseen? It seems to be an art of recognizing the role of the unforeseen, of keeping your balance amid surprises, of collaborating with chance, of recognizing that there are some essential mysteries in the world and thereby a limit to calculation, to plan, to control. To calculate on the unforeseen is perhaps exactly the paradoxical operation that life most requires of us.

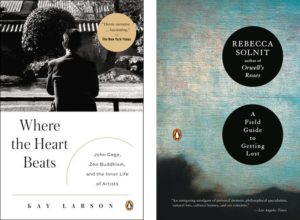

This passage is from one of my favorite writers and favorite books on the creative process, Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost (5). In a series of beautiful essays Solnit evokes, meditates upon, and illustrates the experience of being lost and its relationship to creation, transformation, shapeshifting, or simply making one’s way forward each day.

This question of Solnit’s ”How do you calculate upon the unforeseen?” is one I love chewing on and I have returned to time-and-again since I first read Solnit’s book in 2014. It is a question inspired, Solnit writes, by a declaration of Edgar Allen Poe that “all experience, in matters of philosophical discovery, teaches us that, in such discovery, it is the unforeseen upon which we must calculate most largely” (5).

In this #creativeleadership post I want to reflect a bit on the inevitability, the purpose, the lessons, the possibilities, and the power of the unforeseen. While the unforeseen is something that many of us might like to avoid (I’m now thinking of any number of cataclysms of the past 5 years), artists (in the main) seem to dance with the unforeseen, draw it out, seek it out, and sense it long before others. Across a range of disciplines, one might even conceptualize the creation process that many artists engage as they make new works as a pathway to the unforeseen.

One of the forebears and exemplars of “collaborating with chance,” as Solnit puts it, was the composer and music theorist John Cage. Over winter break I re-read Kay Larson’s fantastic biography Where the Heart Beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism and the Inner Life of Artists as a handful of students in the MA Creative Leadership at MCAD were keen to engage with it. The book is largely an exploration of the influence of Zen Buddhism, including the writings and talks of seminal first carriers of Buddhism to the United States (such as D.T. Suzuki), on Cage’s life and work.

In this second reading I made the connection between Solnit’s “pathways to the unforeseen” and Cage’s principle of indeterminacy. Larson describes indeterminacy and encapsulates Cage’s use of it, writing:

Indeterminacy means, literally: not fixed, not settled, uncertain, indefinite. It means that you don’t know where you are. How can it be otherwise, say the Buddhist teachings, since you have no fixed or inherent identity and are ceaselessly in process?

Inspired by Suzuki’s class, Cage had been exploring ways to write music that was indeterminate both in original intention and in outcome. By using methods of divination (his favorite was the I Ching, the Chinese Book of Changes) Cage could write music with the help of chance. In that way, he could begin with an intention and open it up to the unpredictable. The next step was to write music that obliged the performers to make some of their own choices.

Larson, Where the Hear Beats, 19-20

Cage characterized his work as an experience “the outcome of which is not foreseen” identified with “no matter what eventuality” (Larson, 348). He adopted the use of the I Ching as a method in large part to remove himself (his ego) from the decision-making process with new works. While he quite often set up elaborate constraints or rules in advance of rolling the I Ching, ultimately the work that emerged was the outcome of chance.

While I wouldn’t go so far as to say that all artists work by a principle or process of indeterminacy, the capacity to work in such a way (moving towards the unknown, allowing chance events to influence the work, beginning without a plan or articulated end in sight) does seem to be common among many artists.

Within the frame of organizational processes, I would argue that the opposite of indeterminacy is strategy. What do I mean by strategy? Michael Porter describes it as the big picture of how the organization is going to win in its environment, whatever that is. Put another way, how will you achieve competitive advantage (deliver a distinctive value proposition) given known and unanticipated threats and opportunities?

Since Porter’s initial formulation, and in response to uncertainty and continual disruptions and therefore the difficulty of engaging in long-term strategic planning we have witnessed the turn towards adaptive strategy. While applied to business it grew out of software development and, akin to the scientific process, involves hypothesizing, experimenting, and adjusting as necessary. In other words, try-out short-term strategies and adapt as you need to in pursuit of your longer-term goals.

Lately, the concept of emergent strategy (first coined by Henry Mintzberg but of late most associated with adrienne maree brown) has been gaining ground. Emergent strategy (as it sounds) is not deliberate and does not involve planning. It is developed in response to fluid or unforeseen circumstances (like, say, a pandemic). I am a big fan of brown’s book.

What I have been wondering since re-reading Larson’s book on Cage is whether, to prepare ourselves for a future that we anticipate will be radically different, humans and businesses alike would benefit, at times, from adopting a strategy of indeterminacy. By that I mean an embrace of processes that will by necessity and with intention ensure that we arrive at destinations we cannot imagine, much less describe.

What might a strategy of indeterminacy — a process for putting our organizations on a pathway to the unforeseen–look like? I work at a college running a master’s program. I spent a bit of time lightly pondering this possibility within that general context and came up with a few ideas:

Idea #1 – Wild Card Courses

What if my program annually scheduled a wild card course – a course that would never be logically included in the program. Moreover, what if that course was determined in part by chance? Each year someone would roll the dice to select one of X possible courses. Here are 10 courses that I would never strategically build into the program I currently direct (all but #10 inspired by headlines I’ve noticed recently):

- Tomorrows Deities, Doctrines, & Denominations: What is the Future of Religions?

- Whither Water and Wastewater?

- The New Canary in the Coalmine? Autonomous Mobile Robots & Workplace Hazards

- Building and Using a Vertical Hydroponic System to Grow Vegetation

- Gene Therapy: Risks, Rewards & Quandaries

- Gun Control Policies in China and the US

- GIS Data: Applications in Business, Social Change, and Everyday Life

- Climate-friendly Eating

- Frontiers in Animal Science: Ethics, Economics, and Environmental Sustainability

- Woodcarving

Another idea could be to create a campus-wide course whose content is determined by whomever shows up for it and their interests. No syllabus. No plan. No clear outcomes. It simply emerges in response to the questions, curiosities, and goals of the individuals that come to form the course ensemble.

Idea #2: An admission lottery system

This is not a new idea as admission lotteries already exist; but they are a great example of an indeterminate strategy. Lotteries are already used in Charter schools and some public high schools (in NYC, e.g.). Some institutions of higher learning also use them for incredibly competitive programs. But what if they were adopted at most colleges and universities?

Idea #3: Where’s the College President?

What if every day the president of the college used a random outcome generator to select a spot on campus where he/she/they would set up a laptop and work for two hours?

What would be the outcome of these actions? No one knows; and that is the beauty of them.

I’m by no means suggesting we toss aside strategy in favor of indeterminacy; but I believe there are lessons in the ways that John Cage approached the creation of work and, in particular, engaged processes that enabled him to extend real and imagined boundaries, encounter the unknown, and make what could not have been imagined in advance of the making.

Given widespread recognition of the need to find radically new and beautiful alternatives to many of the ways of being, doing, and knowing that we embraced throughout the 20th century—new ways of relating to the natural world, to ourselves, to each other, to work, to learning, to organizing, to healing, to sustaining ourselves, etc.—it is perhaps worth asking whether we could benefit from engaging creative processes and practices that are, essentially, pathways to the unforeseen.

I’ll leave you with a quote from a talk with Brian Eno and Donna Gratis on the arts’ role in tackling climate change that I attended today.

Surrender is a valuable thing to do. … A lot of our problems come from an excess of control and an absence of surrender.

Brian Eno

What do you think? And have you seen examples of strategic indeterminacy? Or do you have thoughts on how to apply the idea? I’d love to hear from you.