I’ll never be an avid fan, much less an aficionado, of gospel music — but Lift Me Up, Chicago Gospel Keyboard Masters, new from The Sirens, a local independent label, is clearly full of joy and inspiration. It also is notable for documenting a seldom spot-lit but obviously thriving American roots music scene. Art arising from or meant to beget religious transcendence […]

Arhoolie Records (a dozen faves) to Smithsonian

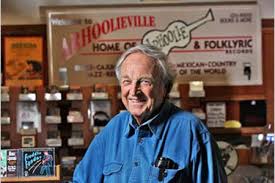

Excellent news on the archival recordings front: Arhoolie Records, the 55-year old treasury of American folk and vernacular musics, has been acquired by Smithsonian Folkways, the non-profit record label of the Smithsonian Institution. So a broad, odd, historic, incomparable cultural catalog, founded and run since 1960 by producer Chris Strachwitz (now 84) enters the public trust. Smithsonian […]

Historic days for US and Cuba, accompanied by jazz

Congratulations to the U.S. and Cuba for advancing our long overdue reset. It’s about time. Jazz at its best has linked our nations for decades, through the tangled history of corrupt dictatorship and revolution, missile crisis, failed invasion, bad relations and trade embargo — and in this recent historic moment, Afro-Cuban-American music is exploding with exciting new recordings. A hint of accords and collaborations […]

Ornette Day, bits of wisdom with video clips

Ornette Coleman’s birthday is today, and his son Denardo has invited everyone to a walk with him from noon to three in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, where his father, the prophet of Harmolodics, is interred near Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Max Roach, Celia Cruz — a very good neighborhood. In Ornette’s honor here are excerpts of […]

Chicagoans’ albums reviewed, author’s edition

My reviews of recordings  by Chicago pianists Larry Novak, Laurence Hobgood and Robert Irving III, percussionist Art “Turk” Burton, and saxophonists Caroline Davis and Roy McGrath appeared in DownBeat‘s January issue, but the print edition limited their length. DB’s rating system ranges from one to five stars (*s), poor to masterpiece. Here’s my text as […]

NEA doubles down on beyond-jazz with 2016 Jazz Masters

The National Endowment of the Arts has doubled down on celebrating jazz beyond “jazz” — music that has exploded historic parameters or preconceptions of  “jazz” conventions — by naming as 2016 Jazz Masters the saxophonists Pharoah Sanders and Archie Shepp — both protégés of the late, great John Coltrane — and Gary Burton, an innovator of technique and content who’s embraced pop, […]

Composer Heiner (Brains on Fire) Stadler @ It’s Psychedelic Baby

Heiner Stadler is a lesser-known but fascinating New York City-based composer who’s stretched he structures and dimensions of jazz with all-star productions including A Tribute to Monk and Bird and Brains on Fire (which I annotated for recent reissue). It’s Psycheledic Baby, the online magazine by Klemen Breznikar taglined “discover the unknown” has published an interview with Stadler — a Polish-born (’42) WWII refugee who heard a […]

Jazz in Jordan: Yacoub Abu Ghosh explains and plays

Jazz and its evolution goes on everywhere – as bass guitarist/bandleader/composer/producer Yacoub Abu Ghosh explained and demonstrated to me in Amman, Jordan last March. Ghosh and his Stage Heroes performed at their weekly gig at Canvas Cafe Restaurant Art Lounge. His new album As Blue As The Rivers of Amman is due to drop July […]

Unusual jazz and beyond music choices in NYC

Hot weather, cool venues through July 30 is theme of my latest City Arts column. Yes, many headliners are on summer European tour, but those who remain reward a hearing . . howardmandel.com Subscribe by Email or RSS All JBJ posts

Jazz lofts as they used to be

Composer Steve Reich said, “Without John Coltrane, there would be no minimalism.” The topic was Hall Overton, the man who arranged Monk’s music, treating jazz as contemporary “classical” composition. The occasion was a panel discussion sprung from an exhibit at the NY Public Library of the Performing Arts about the Jazz Loft hosted by photographer W. […]

US remains jazz central

Jazz is global, but its most ambitious players still flock to the US to soak in its roots and prove they’re part of the scene. Tonight a Parisian septet called Fractale wraps up an eight-gig tour of the States at the Drom in the East Village, after stops in New Orleans, Cleveland and Chicago. From […]

Civil Rights-Jazz document, 1963

Prior to tomorrow’s inauguration, the New York Times (and I suspect many other publications) has focused in many columns, book reviews and reports on Barack Obama’s election as a turning point in the U.S.’s movement towards full civil rights for all people. The entertainment section makes the case for movies having led the way to […]

Armstrong to Ellington to Obama

If anyone needs a primer on how jazz leads directly to the inauguration of Barack Obama as 44th president of the U.S., see Nat Hentoff’s Wall Street Journal article on the history of musicians, audiences, presenters and producers of all “colors” in the struggle for Civil Rights. The march from Buddy Bolden playing in New Orleans’ […]