A complete performance by the Paris Opera Ballet of Jerome Robbins’ Dances at a Gathering, choreographed in 1969 and telecast in 2014. The score consists of piano pieces by Chopin, played by Ryoko Hisayama:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

David is a man of action, so he and Kathy, my sister-in-law, decided on the spot to organize a large-scale family gathering. E-mails were duly sent out, schedules collated, and plans made, the end result of which was that twenty-nine members of our far-flung clan traveled last Saturday morning to Smalltown, U.S.A., to break bread in the half-century-old ranch house where David and I grew up and where he and Kathy now live.

David is a man of action, so he and Kathy, my sister-in-law, decided on the spot to organize a large-scale family gathering. E-mails were duly sent out, schedules collated, and plans made, the end result of which was that twenty-nine members of our far-flung clan traveled last Saturday morning to Smalltown, U.S.A., to break bread in the half-century-old ranch house where David and I grew up and where he and Kathy now live. Fortunately, this storm, unlike its predecessor, passed us by with room to spare, and once it did so, David and Kathy took me through the house, both of them bursting with a mixture of hard-earned pride and understandable anxiety. Had they changed too many things? I’d long since made it as clear as I possibly could that I wanted them to please themselves, not me, but that didn’t stop them from worrying. They didn’t need to. Old and new had been sensitively blended together, and the results were all I’d hoped for and more. “I only wish Mom had lived to see it,” I said, meaning every word.

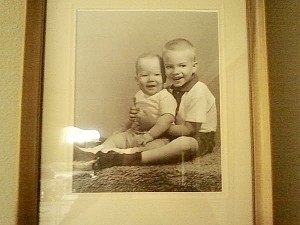

Fortunately, this storm, unlike its predecessor, passed us by with room to spare, and once it did so, David and Kathy took me through the house, both of them bursting with a mixture of hard-earned pride and understandable anxiety. Had they changed too many things? I’d long since made it as clear as I possibly could that I wanted them to please themselves, not me, but that didn’t stop them from worrying. They didn’t need to. Old and new had been sensitively blended together, and the results were all I’d hoped for and more. “I only wish Mom had lived to see it,” I said, meaning every word. But three years later, that empty space has been turned into a comfy, inviting guest room full of the furniture that used to fill my parents’ bedroom—completely redecorated, yet still as familiar and alive as the face I see in the mirror when I shave each morning. One of the pictures that now hangs on the walls is a studio portrait of my brother and me that was taken when we were very young. It is my favorite image of the two of us. Another is a snapshot of Mrs. T and me at our wedding breakfast, glowing as though we were lit from within by love. Memories crowded in on me as I looked around the room, and I half expected to hear somebody say “This play is called Our Town” when I finally switched off the light and went to sleep.

But three years later, that empty space has been turned into a comfy, inviting guest room full of the furniture that used to fill my parents’ bedroom—completely redecorated, yet still as familiar and alive as the face I see in the mirror when I shave each morning. One of the pictures that now hangs on the walls is a studio portrait of my brother and me that was taken when we were very young. It is my favorite image of the two of us. Another is a snapshot of Mrs. T and me at our wedding breakfast, glowing as though we were lit from within by love. Memories crowded in on me as I looked around the room, and I half expected to hear somebody say “This play is called Our Town” when I finally switched off the light and went to sleep. The talk was as straightforward as the food, and I doubt that it would be of any particular interest to outsiders. Much of it was couched in a kind of shorthand, the common tongue of people who have known one another all their lives and so don’t need to explain anything in detail save for the sheer pleasure of doing so. Nobody mentioned what they were reading or what movies they’d seen lately. Instead, ancient anecdotes were retold for the umpteenth time as though they were freshly coined, while past travels and present illnesses were described with identical zest.

The talk was as straightforward as the food, and I doubt that it would be of any particular interest to outsiders. Much of it was couched in a kind of shorthand, the common tongue of people who have known one another all their lives and so don’t need to explain anything in detail save for the sheer pleasure of doing so. Nobody mentioned what they were reading or what movies they’d seen lately. Instead, ancient anecdotes were retold for the umpteenth time as though they were freshly coined, while past travels and present illnesses were described with identical zest. After lunch my brother brought a small TV into the family room, and one of my cousins plugged in a video camera and used it to play back a reel of silent home movies from the Fifties and early Sixties that he’d transferred to videotape. The flickering footage, an unbroken succession of Christmases and Easters and birthday parties, was no more eventful than the table talk, but it didn’t matter: we all crowded eagerly round the set, transfixed by the sight of ourselves when young.

After lunch my brother brought a small TV into the family room, and one of my cousins plugged in a video camera and used it to play back a reel of silent home movies from the Fifties and early Sixties that he’d transferred to videotape. The flickering footage, an unbroken succession of Christmases and Easters and birthday parties, was no more eventful than the table talk, but it didn’t matter: we all crowded eagerly round the set, transfixed by the sight of ourselves when young. I used to think that mine was an ordinary family. As the Stage Manager in Our Town says of Grover’s Corners, “Nice town, y’know what I mean? Nobody very remarkable ever come out of it, s’far as we know.” More and more, though, I find myself wondering just how ordinary it is to be so nice. It’s the dysfunctional families, after all, that get the ink these days, and it looks as though they’ve become the norm in postmodern America—though possibly not. Either way, I know how lucky I was to be born a Crosno. To come from such unfancy people, ordinary though they may be by the standards of the gilded city in which I now live, is to have a leg up in the long race of life, all the way from the starting gun to the finish line.

I used to think that mine was an ordinary family. As the Stage Manager in Our Town says of Grover’s Corners, “Nice town, y’know what I mean? Nobody very remarkable ever come out of it, s’far as we know.” More and more, though, I find myself wondering just how ordinary it is to be so nice. It’s the dysfunctional families, after all, that get the ink these days, and it looks as though they’ve become the norm in postmodern America—though possibly not. Either way, I know how lucky I was to be born a Crosno. To come from such unfancy people, ordinary though they may be by the standards of the gilded city in which I now live, is to have a leg up in the long race of life, all the way from the starting gun to the finish line.

Peter Pan is as familiar to American audiences as any fictional character of the 20th century, give or take…oh, Batman. But “Peter Pan,” the 1904 play by J.M. Barrie in which he first took wing, is now known solely through Jerome Robbins’ 1954 musical-comedy version. Barrie’s original play is seldom staged here, and his other plays are almost entirely forgotten, even though he was one of Edwardian England’s most successful playwrights (in which capacity he now figures on Broadway as a heavily fictionalized character in “Finding Neverland”). That’s how Canada’s Shaw Festival lured me up north this summer, with “The Twelve-Pound Look,” a one-act comedy from 1910 in which Barrie donned George Bernard Shaw’s issue-oriented hat to write a witty proto-feminist parable about what can happen to complacent husbands who seek docile wives.

Peter Pan is as familiar to American audiences as any fictional character of the 20th century, give or take…oh, Batman. But “Peter Pan,” the 1904 play by J.M. Barrie in which he first took wing, is now known solely through Jerome Robbins’ 1954 musical-comedy version. Barrie’s original play is seldom staged here, and his other plays are almost entirely forgotten, even though he was one of Edwardian England’s most successful playwrights (in which capacity he now figures on Broadway as a heavily fictionalized character in “Finding Neverland”). That’s how Canada’s Shaw Festival lured me up north this summer, with “The Twelve-Pound Look,” a one-act comedy from 1910 in which Barrie donned George Bernard Shaw’s issue-oriented hat to write a witty proto-feminist parable about what can happen to complacent husbands who seek docile wives. My time at the Shaw Festival was shorter than usual this year, but I did manage to catch two other fine shows. One of them was Morris Panych’s revival of “Sweet Charity,” a musical that is Shavian in its own class-conscious way, dealing as it does with the travails of a Manhattan dance-hall hostess with a heart of mush (Julie Martell) who longs to land a nice guy but keeps hooking frogs instead. Mr. Panych and Parker Esse, the choreographer, have shrewdly opted to ignore the familiar precedent of Bob Fosse, the director-choreographer of the original 1966 production, and stage “Sweet Charity” without a hint of his corrosive cynicism or hyper-sexualized dance moves. This puts a sweet spin on the proceedings, and Ms. Martell, who was so touching as a too-nice-for-her-own-good girl in the Shaw’s 2012 revival of Terence Rattigan’s “French Without Tears,” plays the same card here to equally engaging effect….

My time at the Shaw Festival was shorter than usual this year, but I did manage to catch two other fine shows. One of them was Morris Panych’s revival of “Sweet Charity,” a musical that is Shavian in its own class-conscious way, dealing as it does with the travails of a Manhattan dance-hall hostess with a heart of mush (Julie Martell) who longs to land a nice guy but keeps hooking frogs instead. Mr. Panych and Parker Esse, the choreographer, have shrewdly opted to ignore the familiar precedent of Bob Fosse, the director-choreographer of the original 1966 production, and stage “Sweet Charity” without a hint of his corrosive cynicism or hyper-sexualized dance moves. This puts a sweet spin on the proceedings, and Ms. Martell, who was so touching as a too-nice-for-her-own-good girl in the Shaw’s 2012 revival of Terence Rattigan’s “French Without Tears,” plays the same card here to equally engaging effect….