In today’s Wall Street Journal I review the off-Broadway premiere of Kenneth Lonergan’s Medieval Play and a San Diego-area revival, North Coast Rep’s double bill of Harold Pinter’s The Lover and The Dumb Waiter. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Kenneth Lonergan is a master of subtle, intimate theatrical naturalism who decisively established himself in “This Is Our Youth,” “You Can Count on Me” and “The Starry Messenger” as one of America’s foremost playwrights and screenwriters. But he is also, lest we forget, a co-author of the screenplay for “Analyze This,” and his broadly comic side comes to the fore in “Medieval Play,” a mile-wide farce about the Great Schism of 1378 which has about as much in common with “The Starry Messenger” as “Airplane!” has with “The Seventh Seal.” “Medieval Play” is billed as “a new and meandering comedy with no contemporary parallels worth noting.” I suspect that this blurb was penned by Mr. Lonergan himself, because it nicely conveys the feel of “Medieval Play,” which is by turns silly and sophomoric, surprisingly smart, very funny and–sure enough–meandering.

If you aren’t familiar with the Great Schism, it’s enough to say that the Roman Catholic Church had two popes between 1378 and 1417, one based in Italy and the other in France, and that the rival claimants to the papal throne, not to mention their respective supporters, didn’t get along even slightly. Enter Sir Ralph (Josh Hamilton) and Sir Alfred (Tate Donovan), a pair of moronic knights who stumble into the middle of this messy conflict and, inspired by Catherine of Siena (Heather Burns), forswear raping and pillaging oand endeavor with limited success to hew to the path of righteousness.

If you aren’t familiar with the Great Schism, it’s enough to say that the Roman Catholic Church had two popes between 1378 and 1417, one based in Italy and the other in France, and that the rival claimants to the papal throne, not to mention their respective supporters, didn’t get along even slightly. Enter Sir Ralph (Josh Hamilton) and Sir Alfred (Tate Donovan), a pair of moronic knights who stumble into the middle of this messy conflict and, inspired by Catherine of Siena (Heather Burns), forswear raping and pillaging oand endeavor with limited success to hew to the path of righteousness.

Mr. Lonergan has turned this conflict into a one-joke play, the joke being that all of the characters in “Medieval Play” speak not in the language of Europe circa 1378 but of America circa 2012….

The problem is that in addition to writing the script, he’s also staged it. It’s not that he isn’t a good director, but anyone else would have ordered him to cut at least a half hour, if not more, out of “Medieval Play.” Instead we get a one-joke show that runs for 155 minutes. If, like me, you have a furtive fondness for brainy juvenile humor, you’ll enjoy yourself anyway, but the fact remains that “Medieval Play” is far too long for its own good….

The enigmatic plays of Harold Pinter are still a hard sell at most regional theaters, so I thought it would be interesting to see how they went over when mounted by a San Diego-area company headquartered in a shopping center. Judging by the unselfconsciously enthusiastic response of the crowd that turned out for the opening night of North Coast Repertory Theatre’s double bill of “The Lover” and “The Dumb Waiter,” it appears that Mr. Pinter has a big future in the suburbs….

David Ellenstein, the company’s artistic director, has put together a dynamite cast led by Elaine Rivkin, a Chicago-based actor who is icebox-cool in “The Lover” as a dissatisfied housewife who dallies each afternoon with…but I mustn’t give it away. Mr. Ellenstein’s cracker-crisp staging points up the laughter in both plays without stinting on their underlying menace…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

The set change for North Coast Rep’s double bill of The Lover and The Dumb Waiter, accompanied by Schumann’s A Minor Piano Concerto:

Archives for 2012

TT: The seductive lure of abstraction

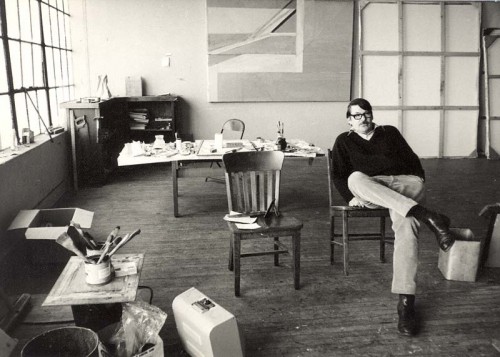

My recent visit to the Orange County Museum of Art’s Richard Diebenkorn retrospective has yielded up a “Sightings” column for today’s Wall Street Journal. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

One of the most satisfying museum retrospectives ever devoted to an American artist is now traveling from coast to coast. “Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Series,” which closed at California’s Orange County Museum of Art two weeks ago and will reopen on June 30 at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., consists of 75-odd abstract paintings and works on paper made by Diebenkorn between 1967 and 1987, the years when he worked out of a studio in the Ocean Park neighborhood of Santa Monica….

One of the most satisfying museum retrospectives ever devoted to an American artist is now traveling from coast to coast. “Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Series,” which closed at California’s Orange County Museum of Art two weeks ago and will reopen on June 30 at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., consists of 75-odd abstract paintings and works on paper made by Diebenkorn between 1967 and 1987, the years when he worked out of a studio in the Ocean Park neighborhood of Santa Monica….

Part of what makes the Ocean Park series so fascinating is that Diebenkorn, who died in 1993, waged a lifelong “battle” with abstraction. He started out as a gifted abstract-expressionist painter. In 1955 he suddenly embraced representation, turning out dozens of figurative paintings that translate the language of Matisse into a wholly personal, semi-abstract style. Then, in the Ocean Park series, he made a decisive return to abstraction, in the process creating the most original works of his career.

To chart Diebenkorn’s stylistic development is to be reminded of the near-overwhelming power of the idea of abstraction in the 20th century. It was even felt by artists who, like Pierre Bonnard and Fairfield Porter, never produced an abstract painting in their lives, but were nonetheless influenced by the way in which practitioners of abstraction created what Diebenkorn called “invented landscapes,” non-objective images that evoked the world of tangible reality while steering clear of literal representation.

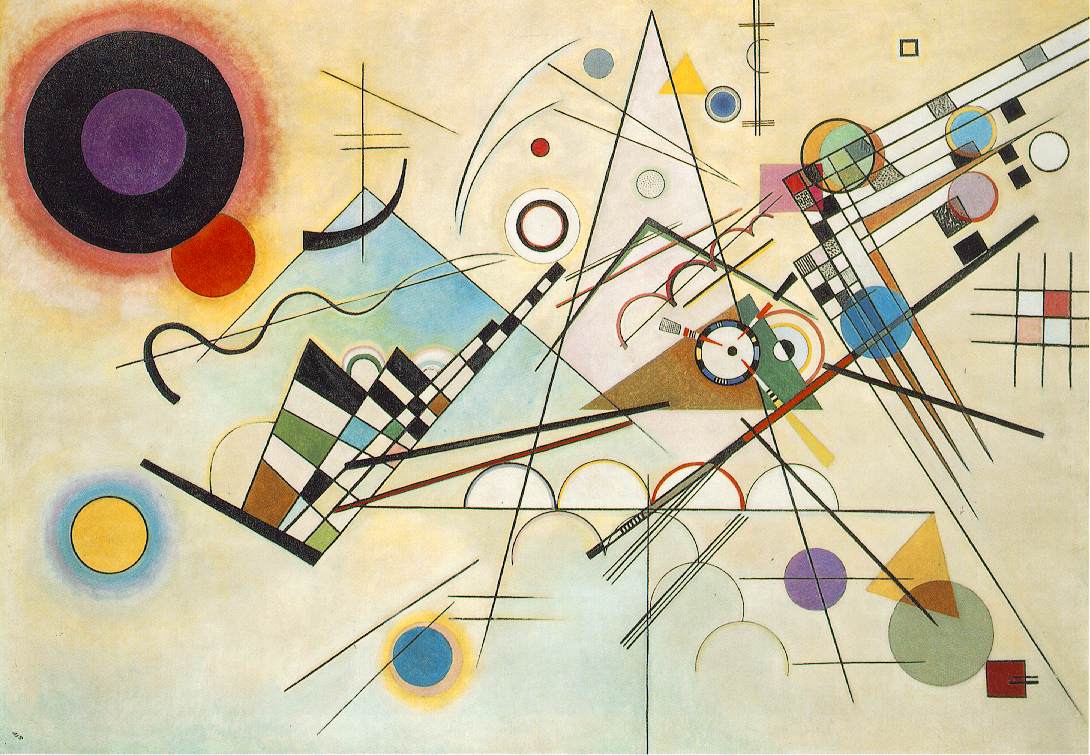

The idea of abstraction is so central to the history of modern art that it left its mark on the work of non-visual artists as well. George Balanchine, for example, is best remembered for the many “plotless” ballets that he made to the music of Igor Stravinsky. The Russian-born choreographer never used the word “abstract” to describe them. “Dancer is not a color,” he said. “Dancer is a person.” But to look at a dance like “Stravinsky Violin Concerto,” in which still-recognizable human relationships are stripped of all literal meaning, is to suspect that Balanchine saw in his youth at least some of the innovative canvases in which Vasily Kandinsky, his fellow countryman, dispensed with the pictorial restrictions of figurative art to become the first abstract painter….

The idea of abstraction is so central to the history of modern art that it left its mark on the work of non-visual artists as well. George Balanchine, for example, is best remembered for the many “plotless” ballets that he made to the music of Igor Stravinsky. The Russian-born choreographer never used the word “abstract” to describe them. “Dancer is not a color,” he said. “Dancer is a person.” But to look at a dance like “Stravinsky Violin Concerto,” in which still-recognizable human relationships are stripped of all literal meaning, is to suspect that Balanchine saw in his youth at least some of the innovative canvases in which Vasily Kandinsky, his fellow countryman, dispensed with the pictorial restrictions of figurative art to become the first abstract painter….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

An excerpt from Balanchine, a 1984 PBS documentary narrated by Frank Langella, in which George Balanchine and Igor Stravinsky are seen in conversation. The clip includes excerpts from three Balanchine-Stravinsky ballets, Agon, Balustrade, and Stravinsky Violin Concerto:

TT: Almanac

“It is after creation, in the elation of success, or the gloom of failure, that love becomes essential.”

Cyril Connolly, Enemies of Promise

TT: Four aces

Gordon Edelstein, the director of Satchmo at the Waldorf, has now nailed down the four key members of the show’s design team. It is, if I do say so myself, a pretty damned impressive lineup:

• Lee Savage, the set designer, is a founding member of Wingspace Theatrical Design. He’s designed shows for Asolo Rep, the Old Globe, the Roundabout Theatre Company, Washington’s Shakespeare Theatre Company, Two River Theater Company, Westport Country Playhouse, Wilma Theater, and the Yale Repertory Theater. His arrestingly stark set for the Berkshire Theatre Festival’s revival of Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts (pictured above) caught my eye when I reviewed that production for The Wall Street Journal in 2009.

• Lee Savage, the set designer, is a founding member of Wingspace Theatrical Design. He’s designed shows for Asolo Rep, the Old Globe, the Roundabout Theatre Company, Washington’s Shakespeare Theatre Company, Two River Theater Company, Westport Country Playhouse, Wilma Theater, and the Yale Repertory Theater. His arrestingly stark set for the Berkshire Theatre Festival’s revival of Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts (pictured above) caught my eye when I reviewed that production for The Wall Street Journal in 2009.

• Ilona Somogyi, the costume designer, is currently represented on Broadway by Clybourne Park. A lecturer in design at the Yale School of Drama, she designed the costumes for Hartford Stage’s productions of The Crucible and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, both of which I reviewed enthusiastically in the Journal.

• Stephen Strawbridge, the resident lighting designer of the Yale Repertory Theatre and co-chair of the Yale School of Drama’s design department, has worked on more noteworthy shows than I can list, including Signature Theatre Company’s recent revival of Athol Fugard’s Blood Knot and the off-Broadway premieres of Bernarda Alba, Black Tie, The Glorious Ones, and A Perfect Ganesh. He has also designed nineteen works for Pilobolus Dance Theatre.

• John Gromada, the all-important sound designer and composer of incidental music for Satchmo at the Waldorf, did the honors for six shows that opened on Broadway this past season: The Best Man, Clybourne Park, The Columnist, Man and Boy, The Road to Mecca, and Seminar. He also scored Michael Wilson’s landmark production of Horton Foote’s Orphans’ Home Cycle, which opened at Hartford Stage, then transferred to New York’s Signature Theatre Company.

• John Gromada, the all-important sound designer and composer of incidental music for Satchmo at the Waldorf, did the honors for six shows that opened on Broadway this past season: The Best Man, Clybourne Park, The Columnist, Man and Boy, The Road to Mecca, and Seminar. He also scored Michael Wilson’s landmark production of Horton Foote’s Orphans’ Home Cycle, which opened at Hartford Stage, then transferred to New York’s Signature Theatre Company.

I am immensely proud to be working with them all.

* * *

Ilona Somogyi talks about her costumes for Hartford Stage’s 2008 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream:

Part of a recording session for John Gromada’s Orphans’ Home Cycle score:

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• Anything Goes (musical, G/PG-13, mildly adult subject matter that will be unintelligible to children, closes Sept. 9, reviewed here)

• The Best Man (drama, PG-13, closes Sept. 9, most performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Evita (musical, PG-13, all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Godspell (musical, G, suitable for children, reviewed here)

• Once (musical, G/PG-13, all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

• 4000 Miles (drama, PG-13, closes July 1, reviewed here)

• Tribes (drama, PG-13, closes Sept. 2, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON ON BROADWAY:

• The Columnist (drama, PG-13/R, closes July 1, most performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON OFF BROADWAY:

• Man and Superman (serious comedy, G, far too long and complex for children of any age, closes July 1, reviewed here)

• Million Dollar Quartet (jukebox musical, G, off-Broadway remounting of Broadway production, closes June 24, original run reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK ON BROADWAY:

• Other Desert Cities (drama, PG-13, adult subject matter, closes June 17, reviewed here)

• Venus in Fur (serious comedy, R, adult subject matter, closes June 17, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK IN CHICAGO:

• The Iceman Cometh (drama, PG-13, closes June 17, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK IN LA JOLLA:

• Hands on a Hardbody (musical, PG-13, closes June 17, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK IN SAN DIEGO:

• Nobody Loves You (musical, PG-13, closes June 17, reviewed here)

CLOSING SATURDAY IN LOS ANGELES:

• Follies (musical, PG-13, adult subject matter, transfer of Kennedy Center/Broadway revival, original run reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY IN CHICAGO:

• Timon of Athens (Shakespeare, PG-13, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY IN COSTA MESA, CALIF.:

• Jitney (drama, PG-13, reviewed here)

TT: The long goodbye (complete)

For those who asked, you can now read all three parts of “The Long Goodbye” in a single file by clicking on the link.

[Read more…]

TT: Almanac

“Where would be the merit if heroes were never afraid?”

Alphonse Daudet, Tartarin de Tarascon

TT: The long goodbye (III)

The next three days were hectic, but also familiar. My brother and I had buried my father, so we knew the routine. We went to the funeral home first thing in the morning to pick out a casket. My sister-in-law went through my mother’s closet and found the clothes in which she would be buried. I drove to the cemetery to arrange for her grave to be dug, got my hair cut and bought a new shirt and tie, then went back to the house to choose three songs to be played at the funeral on Wednesday.

My brother had already decided on the scripture that the minister would read, the Twenty-Third Psalm and the first eight verses of the third chapter of the Book of Ecclesiastes, the passage that begins To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven. They were my mother’s favorites–she had marked them in her well-thumbed Bible–and none of us doubted that he had chosen wisely and well. The songs, somewhat to my surprise, were just as easy to choose. It took no more than a few minutes for me to settle on Aaron Copland’s sweetly austere version of At the River, the Monroe Brothers’ What Would You Give in Exchange for Your Soul, and a recording of Skylark by my old friend Nancy LaMott, at whose deathbed I had also been present sixteen years earlier. I liked the idea of hearing Nancy’s voice at my mother’s funeral, and even though “Skylark” is a love song, not a hymn, Johnny Mercer’s tender lyric seemed to me appropriate to the occasion: “In your lonely flight/Haven’t you heard the music of the night?”

Listening to the songs on my laptop, I began at last to sob uncontrollably. The sound of music had unlocked my heart. My wife put her arms around me. “I think maybe you’d better listen to those records a couple more times if you want to get through the funeral in one piece,” she said.

“I think you’re right,” I replied.

The list of necessary errands kept growing longer–it always does–but everything got done. Come Tuesday night we went back to the funeral home an hour before visitation was to begin. We had decided on Sunday that the casket would be closed to all but the immediate family. Even in the nursing home, my mother had always been meticulous about her appearance, and we knew that she wouldn’t have wanted any of her friends to see her looking the way she did in the last weeks of her life.

The list of necessary errands kept growing longer–it always does–but everything got done. Come Tuesday night we went back to the funeral home an hour before visitation was to begin. We had decided on Sunday that the casket would be closed to all but the immediate family. Even in the nursing home, my mother had always been meticulous about her appearance, and we knew that she wouldn’t have wanted any of her friends to see her looking the way she did in the last weeks of her life.

My own convictions on the matter were long settled. After reading The Loved One and The American Way of Death in high school, I’d decided that the “viewing” of a rouged corpse was a barbarous ritual, a belief hardened in adulthood by the way in which my father’s body was rendered unsightly beyond the possibility of repair by the rare skin cancer that killed him. Thus it astonished me when I entered the chapel, walked straight to the still-open casket, and saw that the undertaker, a kindly and unselfconsciously genial man who took his work with the utmost seriousness, had somehow contrived to erase all the brutal marks of suffering from my mother’s calm, ungarish face.

Everyone fell silent. “I think it would be all right to leave it open,” said Albert, my mother’s older brother. I heard an approving murmur from the rest of the family. Once more my brother and I looked at one another and saw that we were in unspoken agreement. “I think so, too,” I said, and again he nodded. It was the last thing I had ever expected to say, but I was taken aback by the rush of comfort that I felt at the sight of the familiar face that had been so carefully and sensitively restored, and I thought it right for others to feel it as well.

I touched her hand, then leaned over to kiss her forehead one last time. On Sunday it had been warm, but now it felt like a slab of marble. How could anyone who looked so alive be so chilly and still?

Soon the chapel was full. I knew that my mother had been greatly loved, but it still surprised me that so many mourners turned out that evening, and I spent the next few hours hugging people whom I hadn’t seen for years. Many of them came back the following afternoon for the funeral ceremony, and most of the ones who did accompanied us to the cemetery, where my mother’s minister, who had already spoken movingly of her goodness, said a few more words over her flower-covered casket. Then the family drove to the church, where a potluck supper awaited us.

It was the first time I’d eaten such a meal since the night that I dined on baked ham and hashbrown casserole in the fellowship hall of the small-town church where a young friend of mine had just gotten married. I thought of what I’d written about her wedding the next day:

I sat down again to watch my beloved friend embark on her new life. She looked flushed and radiant and determined, and I, perhaps not surprisingly, found myself tugged between hope for her future and curiosity about my own. The time between Thanksgiving and Christmas is uncomfortable for me at best, and I’d been at loose emotional ends for the past couple of weeks….Now I was sitting in a place redolent of my long-ago youth, at once utterly alien and utterly familiar, feeling not unlike the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier, who wandered through her palace at midnight, stopping all the clocks, trying to turn her back on time.

Like time itself, all things must pass, and just as my friend’s marriage came apart a few years later, so had my mother’s long, mostly happy life reached its sad and painful end. Yet here we all were, joking and laughing and eating hashbrown casserole in the fellowship hall of yet another small-town church. The clocks had started again.

* * *

Two days later my wife and I were back in New York, and two days after that we flew to California to spend a couple of weeks seeing shows. I wondered how long it would be before I set foot in Smalltown again, and how much time would go by before my mother’s death felt fully real to me.

The following week we drove down Highway 1 from Santa Barbara to Los Angeles, passing by a seemingly endless string of strip malls. I’ve never seen a place as rootless as this, I thought.

The following week we drove down Highway 1 from Santa Barbara to Los Angeles, passing by a seemingly endless string of strip malls. I’ve never seen a place as rootless as this, I thought.

“You know how I feel today?” I asked my wife. “Empty. Absolutely empty. Like my taproot had been torn out of the ground.”

“I think I know what you mean,” she said, reaching out to squeeze my arm.

(Last of three parts)