Seeing Things: January 2008 Archives

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on January 24, 2008.

Frances Chiaverini and Matthew Branham perform in "Connoisseurs of Chaos" on Jan 21, 2008. Photographer: Julieta Cervantes/Joyce Theatre via Bloomberg News

Jan. 24 (Bloomberg) -- In the hourlong ``Connoisseurs of Chaos,'' the final installment of choreographer Karole Armitage's ``Dream Trilogy,'' six figures twist and angle the postures of classical ballet into a with-it postmodern language.

Set to Morton Feldman's spare ``Patterns in a Chromatic Field,'' the piece offers six characters in search of an auteur. Onstage at Manhattan's Joyce Theater, they are phenomenal bodies that move deftly but lack theatrical personas and the implied emotions, situations or narrative that a top-notch dance maker -- even the most abstractly oriented -- might provide.

For the most part, these dancers operate as a sextet or in pairs. They perform several extended duets, but never with the same partners. Occasionally a trio or quartet serves as witness or perhaps even sympathizer. The consolation, if indeed it is that, is extended toward a figure abandoned after one of the long duets. You might, in a desperate effort to remain awake and attentive, read this as wisps of tenderness stamped out by a pervading hostility between the sexes.

The piece superficially displays a preoccupation with George Balanchine's ``Agon'' and ``Episodes,'' even to the belted leotards Peter Speliopoulos has given the dancers. Yet it lacks the very basic qualities, beginning with incisive structure, that distinguish those works of genius. Armitage, both onstage and off, maintains the attitude that she's doing something new. I suspect she thinks she's going beyond Balanchine.

Forbidding Trees

David Salle, a longtime Armitage contributor and intimate, provides a black-and-white film projection on the backdrop throughout the middle of the piece that gives the dance what little context it possesses. In one lovely passage, the camera gazes through a window at a snow-strewn stand of forbidding black-branched trees. Eerily, on the indoor side of the framed glass, translucent curtains are blown by a breeze that has no logical wind behind it.

Slowly, the camera zeros in on the scene, which then suddenly dissolves into a violent vortex. That trick is trite, but at one point the camera loses the window frame and curtain (elements connoting theater) and just shows the desolate frosty landscape. Armitage has her dancers lie down before it in near- darkness as if it were the landscape of their inner being.

The Feldman score, played live by Felix Fan (cello) and Andrew Russo (piano) was compelling, but it isn't helpful as dance music and Armitage isn't notably musical.

At the Joyce Theater, 175 Eighth Ave. at 19th Street, through Jan. 27. Information: +1-212-242-0800; http://www.joyce.org.

Bigonzetti's `Oltremare'

The Italian choreographer Mauro Bigonzetti, whose ``Oltremare'' (Beyond the Sea) had its world premiere last night, seems to be an affable artist, willing to try anything once. This is the third work Bigonzetti, who heads Aterballetto, based in Reggio Emilia, has made under commission for the New York City Ballet.

The first, the antic ``Vespro'' (2002), was memorable mainly for having the usually inexpressive Benjamin Millepied cavorting atop a grand piano. ``In Vento'' (2006) was graver, with darkly lush inventions for its small ensemble and an incomprehensible relationship among its principals.

``Oltremare'' depicts a small crowd of working-class people, about to abandon the Old World for the New. To a spare, folk- tinged score by Bruno Moretti, the choreographer's frequent collaborator, they mime grief and apprehension, along with the steadfast determination such a displacement requires. Still, the emotions come across as cliches, and the yesteryear look of the dancers' costumes is absurdly at odds with their acrobatic dancing.

The cast did its best -- Maria Kowroski and Georgina Pazcoguin were particularly effective -- but classical dancers are the wrong breed for the subject and Bigonzetti is the wrong choreographer. Spend a day at the heart-wrenching Ellis Island Immigration Museum and you will know why.

The New York City Ballet is at the New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, through Feb. 24. Information: +1-212-721-6500 or http://www.nycballet.com.

© 2008 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on January 15, 2008.

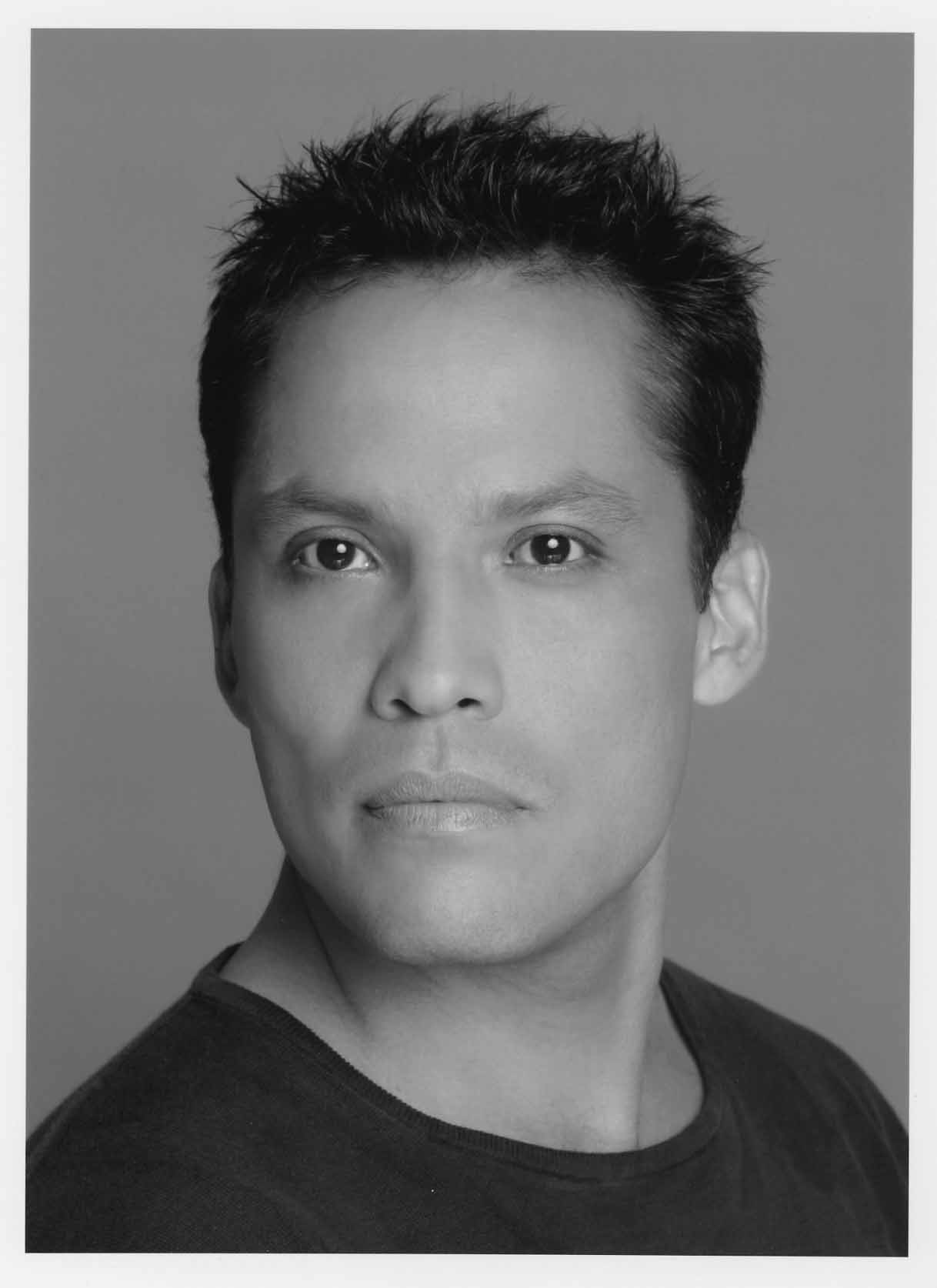

Cedar Lake dancers Acacia Schachte, Oscar Ramos, back, and Jon Bond perform on Dec. 21, 2007. Photographer: Paul B. Goode/GRW Advertising via Bloomberg News

Jan. 15 (Bloomberg) -- Four men and five women are dressed unisex-style, eyes heavily outlined in black, all in stiff, strapless, brief-skirted dresses decorated to suggest spring burgeoning. They shudder, run rampant, scuttle about as if sensing what's coming -- sex, presumably -- and finding it menacing.

``People in Trouble'' could serve as an umbrella title for Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet's show. (The New York City-based company is performing at its own theater in West Chelsea through Jan. 19.) Yet these nine figures who populate the program's most striking piece, ``Rite,'' are pre-human and their initial impact isn't sustained past the mid-point of the work.

Though the score, the four-hand piano version of Stravinsky's ``Sacre du Printemps,'' calls for a Chosen One, a sacrificial maiden, Belgian choreographer Stijn Celis's dance inexplicably finishes tamely, with the woman who began it isolated, unpartnered, a wallflower at the prom.

Canadian Crystal Pite contributed a quieter, more sensitive work, ``Ten Duets on a Theme of Rescue.'' Cleverly, it couples five dancers in shifting situations that range from hostile attraction to pitiful dependence. It's a thin piece that needs expanding and beefing up, but its subtle yet easily decipherable emotion is welcome.

`Symptoms of Development'

Jacopo Godani's ``Symptoms of Development'' is one of those dances so popular today it might have been mass-produced. The Italian choreographer's movement looks fueled by unremitting rage; the pointed one-liners about the evolution of human biology, consciousness and the like are pretentious. The dancers seem to inhabit a glamorous hell, where writhing and whiplash motion is the order of the day and the relief, or at least contrast, of serenity is nonexistent.

While Cedar Lake's ballets aren't memorable, the dancers are terrific: strong, swift and uncannily flexible. I especially admired Ebony Williams, stunning in looks and motion; Acacia Schacte, the queen of fluidity; and Nickemil Concepcion, built like an oak tree yet a vessel of interior drama.

This is not the first dance troupe to owe its existence to a rich woman's fancy. Rebekah Harkness, founder of the Harkness Ballet (1964-74), got there first, with her killer combination of lavishness and vanity. But the largesse of Wal-Mart heiress Nancy Walton Laurie is unique in America today, where most dancers still live hand to mouth. Her Cedar Lake offers its performers salaries they can live on -- with all kinds of benefits ranging from health insurance to studios and a theater to dance in.

Rocky Beginning

Founded five years ago, it had a rocky beginning with many complaints about petty disciplinary actions (like fines for lateness), which seem to have been resolved under the current artistic director Benoit-Swan Pouffer. Running the company like a corporation, a style that makes artistic types uneasy, is an idea that still prevails.

The greatest problem, however, remains the repertory. The company has intended from the first to exist, rootless, on the choreographic cutting edge, but it has yet to commission or acquire an edgy ballet that convinces the audience it has seen the future and approved of it. Cedar Lake's only real hit to date has been the retrospective ``Decadance,'' by Ohad Naharin, artistic director of the Batsheva Dance Company, based in the choreographer's native Israel.

Comprising excerpts drawn from over two decades of Naharin's work, ``Decadance'' was given a one-night-only reprise in Cedar Lake's current run. It, too, contains much frenetic action, but the theatrically astute Naharin offsets the turbulence with passages of calm, mystery and absurd humor. The overall effect is robust and life-affirming, as if the choreographer finds the human animal weird but worth his enduring interest and empathy.

At 547 W. 26th St., between 10th and 11th avenues, through Jan. 19. Information: +1-212-868-4444; http://www.cedarlakedance.com.

© 2008 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

It happened in Copenhagen. Hans Christian Andersen tells us that magic and imagination flourish on Danish soil, and the tourism industry builds on that proposal at every turn. My own frequent visits to Wonderful Copenhagen and its environs--for work and play--make me suspect there's some truth in the idea.

One Friday, many summers ago, the Danish friend with whom I was staying told me about an upcoming weekend fair of vintage items (one of my fatal passions) and offered to drive me out there--god knows where, to hell and gone--in her zippy little white car. We took off the next morning, early, for the opening, so as not to miss a single treasure. Of course it was raining. It seems as if it's always raining in Denmark, or has just rained, or is threatening to do so, or is expressing its melancholy indecision with a fine drizzle.

The fair was a pretty high-end deal, being annual and indoors. Typically, it featured articles for the home: china, silver, glass, mid-century modern furniture--for all of which Denmark is justly celebrated. Historically, however, dress has not been the culture's forte. Until recent decades, dowdiness and dull convention were the norm, considered a virtue perhaps. Yet here it was, hanging high from the top of a door, askew on a wire hanger, the dress that made my heart leap up with Wordsworthian delight, the dress that seemed created for me though it was surely a product of the Thirties, the dress that ignited my usually feeble streak of greed so that all I could think was Mine! Mine! Mine!

It was made of heavy black crepe with a dull finish. The top, including the long sleeves, was encrusted with jet beading and scrolling embroidery boldly laid out in an elaborate design that conjured up leaf and blossom without portraying either literally. The proportions of this magnificent bodice suggested that the garment was intended for a mature lady in possession of a large mono-bosom. I am more delicately endowed. I imagined the original owner of the dress looking like my grandmother in full regalia: majestic and bulletproof.

The skirt was appropriately more reticent, but not without its own subtle dignity. A wide panel of pleats hung front and center. From the waist to the bottom of the pelvis, the pleats were sewn down; below, they flared free. The hemline, grown uneven with time, reached to what I guessed would be midway between the calf and ankle worn by a woman of average height.

Running down the back of the dress, as I was to discover, were twenty-six small buttons and complementary loops, all covered in the fabric of which the dress was made. This was what I've learned to call a "husband dress"--"Hon, would you do me up down the back?" Even if you're very flexible, and I am, once the dress is on, you can only make the top half dozen and bottom half dozen closures, leaving a goodly number of your vertebrae naked to the gaze of society. Husbands and other sorts of housemates not always being around when you need them, I once, en route to one of those affairs requiring "festive dress," had to ask a cab driver to do the job. But I'm getting ahead of my story, revealing that the dress became mine. Eventually. Let's rewind.

Through the half open door from which the dress hung, I could see a tiny disheveled room occupied by a group of mostly unshaven guys of assorted ages in rumpled, none-too-clean work clothes. They were obviously taking a break over coffee, cigarettes, and shots of whatever relieves the pain of getting up at dawn to ferry wares to such a fair's site.

A far more chic woman of a certain age, the epitome of Danish bourgeois style, emerged from a nearby booth offering mostly old porcelain and linens. Gently, she made it clear that she was the proprietress of the dress. "May I try it on?" I ventured. The look on her face suggested that no one had made such an outlandish request before. But she recovered her aplomb, along with the familiar Danish good manners, then scanned the scene and asked, "But where?"

I had shed my physical modesty years before, through quick changes in the wings of the Henry Street Playhouse, where we teenaged dance students performed. There I'd learned that the human body essentially comes in two types with typical variations on the theme, and that once you've viewed several of each genre, you've seen all there is to see.

The seller took alarm at my why-not-right-here? wave of the arm at the public space in which we stood and immediately shooed the men out of the coffee room, put me, the dress, and my friend inside, and firmly shut the door.

I shed my ramshackle flea-marketing outfit and tried the dress on. It was, of course, far too big for me, but it hung just right from the shoulders, and it felt as glorious as it looked. My friend and I emerged from our makeshift dressing room, sought out a full-length mirror (a grand-scale antique, also for sale, at a neighboring booth). Thus provided with a reflection, I turned swiftly and erratically from side to side to catch a glimpse of myself, as if caught unawares, in this foreign costume. Still I couldn't say yes (or, for that matter, no). I adored the dress, but somehow the idea of buying it and actually wearing it seemed to be too much. As they say nowadays, I just couldn't commit.

I managed to say a regretful, rather shame-faced no to the seller, who had the grace to remain expressionless. I apologized to my friend, who only shrugged, used to--indeed, indulgent toward--what she clearly thought of as my peculiar ways. We made a desultory tour of the balance of the market and headed home.

In the dead of night, I lay in bed, obsessing about the dress. It was not merely wonderful for its own physical self. It also harbored an uncanny evocative power. It made me think of Virginia Woolf. I was fully aware, from studying pictures of Woolf (I am a recovering fan of her work), that the dress was not really like her wardrobe at all. I simply knew that I would feel like Virginia Woolf when I wore it. God knows why. I have a man's dressing gown (sumptuous maroon figured silk, floor-length on me) that makes me feel like Balzac. And I loathe Balzac's novels. I just like the idea of him, writing away, at the epic Comédie humaine, to be sure, but, better yet, composing dozens of letters every day as well, longhand of course, fueled by the contents of his constantly refilled porcelain coffee pot, the creditors at the door.

Desire won out. I got up, walked down the hall, and knocked cautiously on my friend's bedroom door. "Ja, hvad er det nu?" (Yes, what is it now?) replied a very sleepy voice. "I can't get that dress out of my mind," I began, standing hesitantly in the doorway. My friend sighed, as if she had known how it would be all along. Summoning up my courage, I went on, "Would you consider--I know it's asking too much, but . . ."

So back we went the next morning, my patient, generous friend and I, in her gleaming white buggy. The excursion was again conducted in the perennial light rain that does wonders for the skin and, coupled with the all too few hours of daylight in the Scandinavian winter, plays havoc with the psyche, making depression many natives' default mode. En route, the rain began to come down hard, indeed emphatically. Accompanying it, came my heart-hammering, belly-gnawing fear that the dress had been snapped up after I had abandoned it the day before. Which, I thought bleakly, would only have served me right. I deserved to be the victim of sartorial retribution.

The dress was still there, thank goodness. Can you believe I insisted on repeating the trying-on ritual, including shooing the men out of the coffee room? (This time 'round they seemed to have accepted the disruption as part of their generally unhappy fate or the very nature of life. The Danes are philosophical folk.) Can you believe I still took a long time to consider if the dress wasn't too strange a costume for me, one of those mad errors that slips further and further toward the darkest recesses of one's closet until an adolescent grandchild commandeers it for Hallowe'en. Then I began to wonder if I could really afford it, not merely as a statement of personal style but in terms of budget. I was a paradigm of indecision. Finally my friend, who may indulge fantasy life--she is, after all, a ballerina--unleashed her practical side and came to my rescue. "Buy the dress," she said firmly, "and let's go and have lunch."

Once having made the decision, we did a little ritual bargaining about the price. (In Italy, I'm told, if you fail to haggle in such circumstances, the seller is disappointed.) I applied my limited Danish to the task, my friend chiming in, charming in her native tongue. The proprietress remained firm, however, and by now I'd realized that if I left a second time without possessing this garment, I'd have been criminally negligent--towards my desires and towards the magnificence of the dress.

I have since worn it for two decades on what I think of as Occasions of Elegance. It cost $60.

© 2008 Tobi Tobias

On Water Flowing Together, Gwendolen Cates's film biography of Jock Soto: "There's an honesty about it that is both innocent and powerful. Like Dan Geller and Dana Goldfine's 2005 Ballet Russes, this film is fueled by simple truths about what it is to be human."

On Soto's partnering class at the School of American Ballet: "Without words, he hoists one of the girls--a bantam-weight, granted--to his shoulder, where she sits, elegantly poised in the air while he walks forward, as if on a stroll in the park. Then he lowers her slowly, seemingly handling a fragile, otherworldly creature, until her feet touch the earth. Continuing, still in silence, he demonstrates a brief, beautiful phrase with her, then summons the rest of the students to take it up, traveling down the diagonal two by two. Every girl becomes a princess in her own imaginary kingdom, thanks to her trusty, Soto-bred cavalier."

The full article appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on January 2, 2008. To read it, click here.

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary