Douglas McLennan: June 2009 Archives

"I don't think we are in a recession, I think we have reset," he said. "A recession implies recovery [to pre-recession levels] and for planning purposes I don't think we will. We have reset and won't rebound and re-grow."So how will we get our news?

"All content consumed will be digital, we can [only] debate if that may be in one, two, five or 10 years," added Ballmer.

"There won't be [only traditional] newspapers, magazines and TV programmes. There won't be [only] personal, social communications offline and separate. In 10 years it will all be online. Static content won't cut it in the future," he added.

What was the difference? The new ticket services not only had seating charts and more information about performances, you could see the prices of every seat, and when you clicked on a seat, you could see the view of the stage from that seat. Customers loved it. Not only did online ticket sales take off, the average ticket sale went up 14 percent. Turns out when you put more control of the experience in the hands of the customer, they use it. And they choose to treat themselves better.

Nike has learned a similar lesson. The company's Nike+ pairs running shoes with monitors that measure a runner's workout.

Nike has learned a similar lesson. The company's Nike+ pairs running shoes with monitors that measure a runner's workout.Few things illustrate the power and promise of Living by Numbers quite as clearly as the Nike+ system. By combining a dead-simple way to amass data with tools to use and share it, Nike has attracted the largest community of runners ever assembled--more than 1.2 million runners who have collectively tracked more than 130 million miles and burned more than 13 billion calories.

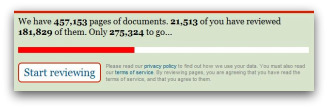

The Guardian newspaper found itself at a distinct disadvantage recently when the government dumped half a million million documents detailing expense claims submitted by members of parliament. Sorting through the documents would take reporters a year. So the Guardian decided to enlist readers. Editors put the pages online and asked readers to look at them and report back what they found.

The Guardian newspaper found itself at a distinct disadvantage recently when the government dumped half a million million documents detailing expense claims submitted by members of parliament. Sorting through the documents would take reporters a year. So the Guardian decided to enlist readers. Editors put the pages online and asked readers to look at them and report back what they found.Within a few days more than 20,000 readers had reviewed 181,829 pages and the newspaper began reporting on what they had found. Editors had mobilized their community to help produce the product, and readers were enthusiastic about it.By making it feel like a game. The Guardian's four-panel interface -- "interesting," "not interesting," "interesting but known," and "investigate this!" made categorization easy. And the progress bar on the project's front page, immediately giving the community a goal to share.

"Any time that you're trying to get people to give you stuff, to do stuff for you, the most important thing is that people know that what they're doing is having an effect. It's kind of a fundamental tenet of social software. ... If you're not giving people the 'I rock' vibe, you're not getting people to stick around."

This is the kind of thinking behind the Indianapolis Museum of Art's

This is the kind of thinking behind the Indianapolis Museum of Art's Are most people interested in this level of detail? No. Is it a bit scary to have your endowment figures up for everyone to see in this financial market? Absolutely. But if people take more ownership of a community when they have more information, and if they feel encouraged to participate in that community because they can see how it works from the inside, then this is a smart strategy for growth.

Bill Ivey was chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts during the Clinton administration. More recently he has been director of the Curb Center at Vanderbilt University, and, after last year's presidential election, ran the Obama administration's transition team for culture. So what place will the arts have in the new administration? Ivey says the jury's still out.

As for another big issue that surfaced during the transition - should America have an Arts Czar, a Secretary of Culture? - Ivey has some surprisingly strong feelings about it. Here's part of my interview with him last week in Seattle:

Ivey is also the author of Arts, Inc., which argues that "the expanding footprint of copyright, an unconstrained arts industry marketplace, and a government unwilling to engage culture as a serious arena for public policy have come together to undermine art, artistry, and cultural heritage--the expressive life of America."

Every business model relying on intellectual property law (patent and copyright) is heading for massive deflation in our lifetimes. We've seen it with the music industry and newspapers already. The software industry is starting to feel it with the maturity of open source software, and the migration of applications to the cloud. Television, movies, and books are next. I've come to question the ability of copyright and patent law to foster innovation, but leaving that aside, the willingness of people to collaborate and share, and the tools provided for it on the internet, may render these laws obsolete.

And that means:

Journalists, auto workers, record industry players, retail sales clerks, and marketing staff are forced to go looking for work in shrinking markets. These businesses are either suffering from old business models based on increasingly artificial scarcity (newspapers, music, marketing, software development), or are able to do more work with the fewer resources due to the newly created efficiency (retailers). In short, businesses relying on artificial scarcity created by intellectual property law, are businesses most susceptible to deflation.

In the TV Age the tube has dominated breaking news. Watching crucial moments of a big dramatic story on TV can be compelling, and the TV news audience has dwarfed newspaper readership. It is accepted wisdom that TV owns the dramatic breaking story; newspapers bat cleanup.

In the TV Age the tube has dominated breaking news. Watching crucial moments of a big dramatic story on TV can be compelling, and the TV news audience has dwarfed newspaper readership. It is accepted wisdom that TV owns the dramatic breaking story; newspapers bat cleanup.But maybe not. Watch a big story on cable news and you're in for acres of boring vamping and conjecture wrapped around the couple of minutes here and there that you really do want to see. And those dramatic couple of minutes are endlessly repeated until you're tired of seeing them. Fact is, video is a linear medium that sometimes isn't very efficient at advancing coverage of a story.

On the other hand, text - lowly text - may turn out to be more efficient. Text isn't real-time. Its order can be rearranged on the fly by the reader. It can point to other things - video, photos, charts, diagrams, reference information. More important, it can be skimmed to quickly find only the pieces you're looking for. With mobile devices, text can be transmitted by anyone, quickly and easily.

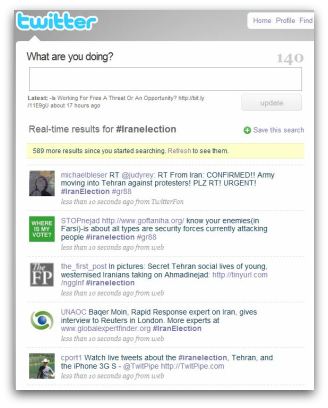

In the past week, the most compelling coverage of the protests in Iran hasn't been on television, it's been on the internet via Twitter. Thousands of people have been tweeting, reporting what they have seen and pointing readers to photos and video clips posted on YouTube.

Why more compelling? First, it has democratized the reporting, giving access to thousands of eye-witness reports from all over the country, rather than the accounts of a few correspondents who may not have the breadth of access that the thousands of volunteer eye-witnesses do. Perhaps just as important, the short texts are skimmable, and a number of websites have endeavored to collect and sort through the raw reports. Twitter and YouTube have made coverage that is customizeable by readers. No more Wolf Blitzer endlessly filling time while awaiting new developments.

A funny thing has happened on the way to the YouTube revolution: video everywhere has elevated the role of text. People want to watch video, but on their own terms and not in a linear stream decided by someone else. The easiest way to sort information isn't by video, it's by text. Why do people text one another rather than dial their phones and talk? Texts, in an odd way, seem easier.

In the next week or so, Google will release its Google Voice service, which will take your voice mails and convert them to text transcriptions which can be emailed to you. Why? Because voicemail can be clumsy; text takes the interaction online, where it can be controlled by the recipient. It might be easier to record a voice message, but reading that message is more efficient than dialing in to listen to a recording.

That is not to say that listening to someone's voice - the tone, the inflection, the nuance - doesn't provide more information than text. And text doesn't convey the visual experience of video. But in the future, video and audio might be considered the drill-down rather than the headline, a curious flip of the media world we have recently known where TV has offered the raw immediacy and newspapers weigh in later to add the depth.

Google has asked prominent illustrators if they'd like to create new skins for the company's Chrome browser. Here's the catch: Google isn't offering any money for the designs. Google expects artists to contribute for free. Understandably, many illustrators and artists are protesting; a rich company like Google can afford to pay, and asking people to work for free devalues the work.

Stan Schroeder at Mashable picks up the case:

There's a reason, however, why they aren't offering monetary compensation for skinning Chrome. Google didn't set the price for such work at (nearly) zero; the community did... even professional illustrators and designers should understand that they don't get paid for these types of projects because Google is cheap, but because there's a huge community of artists who have been doing it for free for years.

There's always been a tension over the tangible and intangible value of work and compensation. If I come to work for you and you pay me a decent salary and I become a star, I'm likely to think my employer got a hell of a bargain and should pay me more because of my stardom. My bosses take the position that they made me a star by giving me the opportunity, training, resources and platform to become one and I owe them. Who's right?

There's always been a tension over the tangible and intangible value of work and compensation. If I come to work for you and you pay me a decent salary and I become a star, I'm likely to think my employer got a hell of a bargain and should pay me more because of my stardom. My bosses take the position that they made me a star by giving me the opportunity, training, resources and platform to become one and I owe them. Who's right?In the old model, we've upped the demand for my services and I get to ask for more compensation from my employer or I can go elsewhere. But now that the internet has made production and distribution platforms cheap and accessible by anyone, many more people have the opportunity to go out and become stars at whatever they do.It also means competition increases, and things that many can do drop in value.

Why would skilled workers work for free? To develop their skills, to show what they can do to others, to improve something that matters to them, to contribute to a community that matters to them, for social status. There are lots of reasons. The point is: if people are willing to do something without being paid money, others won't pay money for it. Just as important to remember, though: people wouldn't work for no money if they weren't getting something else out of it, whether it's status, personal promotion or just satisfaction for doing it.

I'm not arguing that people shouldn't be paid money for their work, but the fact that many are not only willing but happy do so, is a reality anyone in the new economy has to deal with. The choice for anyone running a business is one of opportunity cost or advantage. Giving away something for free gets a bigger audience; charging for something means a smaller audience. If your business model is built on needing a larger audience, then

there's pressure to lower the cost. If, on the other hand, your

business model is built on the kind of audience you have, then size of your audience probably doesn't matter so much..

Washington Post executive editor Marcus Brauchly succinctly defined the problem in a reader chat this morning:

We fund our news operations from revenues generated largely by advertising. Online advertisers pay for an audience--the larger, the better. If we put up a wall that readers would have to pay to cross, and then readers didn't cross it, our advertising revenues would probably suffer.

Probably for sure. Newspapers have a problem of scale and a business model based on large scale audience. For individual workers, the kind of audience you need (ie: your employer) has always been more important. But that now is changing too. Last word to Schroeder:

There's no reason for pro artists, designers and illustrators to fear. Some aspects of their work - those that can be crowdsourced or those that aren't hard to do (perhaps with the help of technology) - will lose in value. But there will always be a market for professionals, because most of what they're doing cannot be done by just anyone. It's important, however, that professionals in any trade learn, understand and ultimately adapt to the fact that social media and new tools that the Internet has provided us with are changing the landscape of their profession.

Is this true? I'm not sure. Where's the market for professional critics and reporters and editors right now?

Richard Cahan had an idea. If theatres were worried about programming risky work because audiences might not shell out money to see it, and audiences were balking when it came to taking a chance on something new, why not just eliminate the risk?

Richard Cahan had an idea. If theatres were worried about programming risky work because audiences might not shell out money to see it, and audiences were balking when it came to taking a chance on something new, why not just eliminate the risk?Cahan's a part-time program officer with the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation in Chicago, so he came up with a plan: the foundation would back a money-back guarantee for some plays and take the risk of new work out of the ticket-buying equation. He went to the theatre community with the plan:

Cahan was surprised to find that "some people thought it was a bad idea. They were worried about the commodification of theater," thought there was already enough tension there, and didn't want to emphasize it.I love the phrase "commodification of theatre". Theatre as product. Which, of course, it is if you're paying money to see it. There is, of course, another transaction going on - the payment of one's time and attention, which is often undervalued. So what basis would you use for asking for your money back? For me it would be indifference. Too many things I see are performed without passion. A faulty premise not well tested during rehearsal, a performer going through the motions, a dumb idea nobody challenged...Cahan had stumbled into quasi-taboo territory. Most media coverage of theater is written as if the author were blissfully ignorant of the fact that normal people have to fork over hard-earned cash to be in the audience. Critics, who usually get the best seats in the house without having to pay for them, aren't compelled to think about what it means to pony up for a ticket and then have to peer between heads from a seat under the balcony at a show that might turn out to have been overrated.

When critic Kelly Kleiman brought the cost-value equation into a blog discussion on the WBEZ Web site a couple months ago, she reaped abuse from numerous commentators, including some of her peers in the critical ranks. But Kleiman, who wrote that her reviews are intended to provide her "listeners--people who might or might not spend $45 a ticket to see this production--with an answer to the question of whether they'll get their money's worth," had her finger on the real world's pulse: if you're selling tickets, you're dealing in a commodity, and if you're buying them, price and value count.

How do good ideas take hold? It's not enough to talk about them; the context in which you talk about them has to be right. How do producers pitch ideas for movies? They relate them to other movies that have already been successful. So Terminator meets Cheaper by the Dozen gets you to Kindergarten Cop (don't ask).

Bilbao Guggenheim gets you to a whole new generation of museum buildings as art. American Idol gets you to the idea that audiences ought to participate in a more active way in what they see or hear. Ideas need the context of other ideas to get traction; without the context, the next ideas don't have a chance to take hold.

The problem then, isn't so much having good ideas, it's making sure people are ready to hear your good ideas. Successful entrepreneurs spend lots of time thinking about how to do this.

I'm at the League of American Orchestras conference this week to talk about social media and the arts, and I'm hearing lots of great ideas.

So how do good ideas get currency in classical music? Say I'm a composer and I've written a symphony. I convince a conductor to take a look at it. Then get it on a program and performed. Suppose, despite the odds, I do, and the audience loves it. Suppose even, that the orchestra is a good orchestra and the conductor has a great reputation and we can even make a recording of it. And that recording is pretty good and it wins an award and it's a big award. Suppose all that.

Where does it get me? Will other orchestras be clamoring to perform my symphony? Will other conductors be clamoring to get a crack at my next piece? Will I take my place alongside other composers as our work and ideas are debated? Will our music be the new context for the next composers coming along?

I don't think so.

Or suppose I'm a conductor and I go to the right schools and against the odds I get the right assistant jobs and some experience, and I have great ideas and the critics (back when there were still critics) give me good reviews. I'm looking for a job. But every music director job at even small and medium-size orchestras, according to Henry Fogel, gets 100-150 applicants. These are lottery numbers, but still, I beat the odds and get the job.

But say I get the job and my orchestra in my small town is good and I build it into a blazing success. What then? Are other orchestras clamoring for my attention? Do I get invitations to lead other orchestras?

Unlikely.

Why? A couple of years ago, in a debate with a group of about a dozen prominent music critics about where music was headed, I was struck by how the conversation kept breaking down whenever anyone tried to talk about specific music.

The problem wasn't that there wasn't good music to talk about; it was that there was no context by which to measure success.Without it, there's almost no way to build consensus. Without consensus, ideas, even great ideas, tend to float aimlessly.

In theatre, if a play has a regional success, or sells tickets on Broadway or wins a Pulitzer, there's a bidding war the next season to see who gets the rights to perform it locally. If a book gets good reviews, gets a mention on NPR and wins a prize, it hits the bestseller charts and builds demand for the next book. In visual art, an influential collector or dealer getting behind an artist's work virtually guarantees a market for it.

But classical music success seems largely immune to great reviews, big prizes and enthusiastic audiences. There is great music. There are excellent orchestras. What there isn't is a functioning system for identifying and promoting the best work and people to build consensus. Is it possible that orchestras have spent so much time worrying about how to survive that they have neglected to define the terms for success (and, importantly, for failure)? Or is it that we're just in a period of transition, and, at least for now, consensus just isn't possible, even for a great idea?

Craigslist stole in and took the classified ad business away from newspapers while they weren't looking. The same thing seems to be happening to A&E reviews and listings with Yelp. Newspapers have been doing a worse and worse job of reviewing local performances. And most newspaper listings are not very good.

Craigslist stole in and took the classified ad business away from newspapers while they weren't looking. The same thing seems to be happening to A&E reviews and listings with Yelp. Newspapers have been doing a worse and worse job of reviewing local performances. And most newspaper listings are not very good.Yelp is a community built around reviews. Yelp users review everything, and as its user base has grown it has become more and more useful as a way to sort out what you're looking for. I use it to find restaurants when I'm traveling.

Increasingly, Yelpers are using the site to review performances. Newspapers, rather than step up their game, seem to be conceding this segment of their audience.

Mark Potts:

What's happening is that Yelp now has enough crowdsourced participants and reviews of enough businesses in enough markets to be a truly useful tool in trying to decide what to do for entertainment (and more). Combined with search and geo-location (Yelp's iPhone app is indispensable), Yelp is becoming a very powerful tool.That's a big deal for newspapers, which long have touted their allegedly encyclopedic knowledge of the local scene, as well as their restaurant and entertainment reviewers. But why grapple with clumsy newspaper entertainment-guide and calendar interfaces, and take the word of a single, over-stretched reviewer, when you can quickly see what the crowd is saying on Yelp about the place you want to go? And as Yelp expands its reach beyond restaurants and entertainment locations into other local businesses, it's becoming even more valuable. Advertisers will be sure to follow.

A week ago New York Magazine art critic Jerry Saltz launched a bomb on his Facebook page:

"The Museum of Modern Art practices a form of gender-based apartheid. Of the 383 works currently installed on the 4th and 5th floors of the permanent collection, only 19 are by women; that's 4%. There are 135 different artists installed on these floors; only nine of them are women; that's 6%. MoMA is telling a story of modernism that only it believes. MoMA has declared itself a hostile witness. Why? What can be done?"

After hundreds of comments from his Facebook Friends, he re-posted the original entry three more times to make it easier for readers to follow the discussion. Three or four additional follow-up posts on the topic brought in hundreds more comments and Saltz told his community that:

In the next month I plan to write a cover letter and amass all of your FB comments in regards to the paltry percent of women artists on the 4th & 5th floors of the permanent collection and send the package to the following MoMA officials...

Before he had the chance,the museum responded, sending a note to Saltz to post on his page:

"Hi all, I am (Kim Mitchell) Chief Communications Officer here at MoMA. We have been following your lively discussion with great interest, as this has also been a topic of ongoing dialogue at MoMA. We welcome the participation and ideas of others in this important conversation. And yes, as Jerry knows, we do consider all the departmental galleries to represent the collection. When those spaces are factored in, there are more than 250 works by female artists on view now. Some new initiatives already under way will delve into this topic next year with the Modern Women's Project, which will involve installations in all the collection galleries, a major publication, and a number of public programs. MoMA has a great willingness to think deeply about these issues and address them over time and to the extent that we can through our collection and the curatorial process. We hope you'll follow these events as they develop and keep the conversation going."

This in turn let loose a whole new flood of comments, many criticizing the idea of a "Modern Women's Project." And the debate rages on as Saltz explained that now that the group has MoMA's attention, it should press the museum to rectify an injustice. Saltz has nearly 5,000 Facebook friends, and he's built his community by positioning himself as much as a discussion leader as a traditional critic.

There was a time when arts organizations (following good corporate example) stayed aloof from criticism, preferring not to respond publicly when criticized unless forced. Many's the time that the subjects of negative arts stories we have posted on ArtsJournal have contacted me to try to correct the record as they saw it. In each case (maybe 20 over the years), I offered a chance for the institution to write a rebuttal to the story and said I'd post it on AJ. How many do you think took me up on the offer? Three.

Most figured that even though the story was wrong, it would blow over more quickly if it was ignored. But in the digital age these stories stay out there forever, and besides, I'd argue, responding is an opportunity to engage.

And so it is. And so MoMA engaged with Saltz's group, and good for them. Except.

One of the great things about social media is that it encourages personal interaction. One of the challenges for institutions is to not sound so institutional. In MoMA's official response, the unnamed "we" have been "following your lively discussion" with "great interest" could hardly be more institutional. Then there's "this has been a topic of ongoing dialogue at MoMA" and the even more co-opting "we welcome the participation and ideas of others in this important conversation." And finally: "We hope you'll follow these events as they develop and keep the conversation going."

Could it be any more condescending?: "We noticed you're having this lovely little discussion over here at the kids' table... pat, pat, pat... How charming of you..." If someone spoke to you like this in real life you'd roll your eyes and walk away. Moreover, the response doesn't address the issue with either a direct acknowledgment of it (you're right, only four percent of the artists represented on those floors are women) or that there really is a real disparity of gender. Instead, it's an attempt to deflect the criticism by appealing to a broader context and sidestepping the issue as it was raised.

How could the museum think that anyone would be placated by such a statement? Indeed, I think it made things worse because the museum looks intellectually dishonest in front of a core audience that really cares.

My purpose here isn't to debate the gender issue, but to point out that traditional PR notices are not only ineffective in this new era of many-to-many communication, but can make things worse. And what might have been a real opportunity to meaningfully engage this community has been lost. Just because this conversation didn't bubble out in public earlier doesn't mean that people haven't been having it privately for years. To not confront it honestly and openly now that it has gone public this way does real harm to MoMA.

Not surprisingly, the debate roars on on Saltz's page, and he's even created a new group on Facebook Jerry Saltz; Seeing Out Loud to continue to press the issue. A day or so after it was created, it already has 587 members.

The way for newspapers to charge for content is not rocket science. They must create new types of high-value, probably niche, content, communities, and/or services that are unique enough that people will be willing to pay for them. That's tricky when your newspaper has laid off a big chunk of its editorial staff. But if it's shedded stuff that others do better on the web -- no more local movie critic, TV editor, books editor, etc. -- then perhaps there can be room to rethink what a "newspaper" is about and start creating new content and services that break out of the newspaper box.

Newspapers have already lost many of the things they used to do to national web players that do a better job and can serve local audiences. The discussion now should be on what new things a newsroom full of journalists can do that are outside what we've known and valuable enough to get people to pull out their credit cards.

Last week executives from major newspaper chains met secretly (yeah, right) in Chicago to discuss putting their content behind pay walls, taking care of course to not collude on price fixing (of course). So apparently by the end of the year several chains will ask us to pay to read their product. There have been many critiques of this idea (Scott Rosenberg has a great roundup here). Outing also makes a great observation about the faultiness of the conceptual thinking behind pay-per-view:

In an era when people expect news to reach them in many ways, in many formats, and on many devices, it's anachronistic to return to publishing news on one medium primarily and handicapping distribution on digital media forms, like the web, where different rules apply.

So journalism has to change. Everyone gets that. But most new models I see are really traditional journalism gussied up in new tools. Or, they reinvent in such a way that throws away some traditional journalistic values.

So journalism has to change. Everyone gets that. But most new models I see are really traditional journalism gussied up in new tools. Or, they reinvent in such a way that throws away some traditional journalistic values. Most conceptual re-imagining of journalism is still tied to the events-of-the-hour sort. What happened today. Traditional journalism has been good at this kind of reporting, not just because it was a useful service, but because it was possible. This is a mass media model - content that can be somewhat targeted and personally delivered but not personally customized to any great degree.

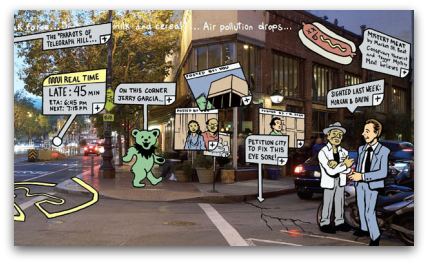

Getting more personalized information is both easier and more difficult. Want to know the value of the house down the street or the crime statistics on your block? There's the library (the easy part) and now the web. But if you want to know where your specific bus is and when it will arrive, that was more difficult. The most important news while you're waiting for the bus is probably when it's going to get to you. But ten minutes from now, while you're on that bus, the most important news might be the traffic. And after that, the latest people are saying about that new restaurant you were planning to go to for lunch.

Reporting on larger events of the day is still important. But this individual news, accessible exactly when and how you need it is likely more personally compelling. Most news organizations don't think of this stuff as journalism. But why not? Are comics journalism? The crossword puzzle? There are lots of things journalism hasn't been, for one reason or another, and now could be. Here's one scenario imagined at Fast Company:

Peer into the future and imagine the landscape of information that could be available to you. When connected to high-speed, wireless Internet, two people looking at the same street could access completely different information. One might call up postings for nearby school events, while the other might opt to see news about a campaign to fix local sidewalks following the last earthquake. Users could add to this cloud of news right from where they stood, or from anywhere else with network coverage. This customized mix of news feeds could include the local, international, social, personal--or just plain weird.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog

Recent Comments