Artopia: February 2008 Archives

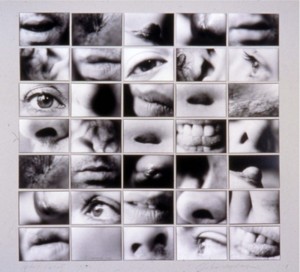

Carolee Schneemann: Portrait Partials

What Feminism Was

"WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution" is a chance to take a look at the pioneering days of feminism in art, from 1965 to 1980. This huge survey originated at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art and is now at P.S. 1 - MoMA, Long Island City, to May 12. Capturing the raucous, contentious, feminist diversity, Connie Butler (who in '05 moved from MOCA to MoMA, where she is now curator of drawings) demonstrates that much of the art by women in this ancient period was superior to dead-end formalist painting and many of the largely male prerogatives of the time.

Without an equal place for women artists, we cut ourselves off from the talents and perceptions of more than half the world. Art, as far as I can tell, is not gender-specific. Hence the effort to rediscover forgotten women artists and the self-consciously feminist art that began in the mid-'60s.

Feminist art, however, cannot be seen as another art-market niche. It may have been an art movement, but it is clearly not a style. Although there were attempts to position feminism as anchored either to centered imagery or, oddly enough, the thoroughly decentered grid, neither trope stuck. Proponents seemed not to notice that both formats had already been readily used by male artists. Certainly some of Georgia O'Keeffe's flowers can be seen as vaginal, but so are Kenneth Noland's targets, right? And I never quite understood why grids were particularly womanly. For every association with weaving -- which is sometimes a male pursuit too -- there's an association with graph paper and chessboards. I suppose it must have been shocking for certain male artists to find out they were unintentionally making "feminine" artworks.

Martha Rosler: Nature Girls (Jumping Janes)

And Then What Happened?

If the truth be known, feminism in art, as in life, was political, and this is probably why it was suppressed in the '80s and '90s. That S-word might seem excessive, but I can think of no other term. It may have outwardly been a benign suppression, frosted over with exhibitions for a few good-girl or bad-girl artists, but look in the galleries now. After so many successful feminist actions by feminist pioneers, the slippage has been appalling. Art history may be cruel, but commerce-driven art is merciless.

We do indeed now have the Elizabeth A. Sachler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, at the center of which is the permanent display of Judy Chicago's breakthrough Dinner Party -- still controversial, still moving. But in spite of the opening exhibition last year -- "Global Feminisms," curated by Linda Nochlin and Maura Reilly -- that attempted to survey feminist art since 1990 -- we still need WACK! to gather up the feminist pioneers.

Now more than ever we need their inspiration. Discrimination continues. Here is an appalling example: The inaugural exhibition of LACMA's Broad Center of Contemporary Art sports only four women artists out of 29. You can blame that on the collecting habits of Eli Broad -- currently our favorite whipping boy, since he apparently reneged on his implied intention to give his collection to LACMA -- or you can blame whomever approved the less than broad Broad show.

What "WACK!" Lacks

First of all, I would like to point out there is a difference between feminist art and art by just any woman. The uninformed indeed might walk away from "WACK!" thinking that all art by women is feminist.

Perhaps because it is difficult for women to make art?

Doubtful, since half or more of all art students are women, most of whom graduate, which means quite a few people have agreed that they are able to make art of some sort or another -- even their male art teachers.

Because it is difficult for women artists to achieve art visibility?

This was certainly the case before the '70s, and despite that window of opportunity -- here honored -- we still face that general situation. It is perhaps a tiny bit easier for women artists now, but not much.

And why is this so? Why do male artists dominate the marketplace and its servants, the art media?

I do not blame the critics, who haven't had much of a say in anything for years. I do not blame the curators; they usually follow the galleries. I do not blame the galleries; the economics of their situation makes it imperative for them to follow the collectors, their customers. These, more than ever, claim power and can threaten to buy directly out of studios at discount prices and even from classrooms. As investors, they go by what they know. No art by a woman has ever gained the astronomical resale value of the art created by males. And yet we know, don't we, that artmaking is not gender-specific.

The apolitical and anti-activist provisos might apply to male artists too: why aren't the politically informed works of Hans Haacke or the devastating, accusatory paintings of the late Leon Golub even within monetary spitting distance of any of the current auction superstars? At least, as male art, their work gets shown. Golub, as demonstrated currently at LACMA, was collected even by Mr. Broad.

Lynn Hershman: The Roberta Breitmore Series. Photo courtesy Lynn Hershman Leeson.

Why You May Be Confused

It may be clever; it may be subversive; on the other hand, it may be totally fallacious. But curator Butler has a thesis.

Provoked by the dizzying diversity of more than a hundred artworks, the confused viewer might want to take a look at the catalogue, since no wall text clearly explains the incongruent display. Yes, Feminist Art is not a style, but it was -- or is? -- an art movement.

Butler writes:

Many of the artists in "WACK!" do not necessarily identify themselves or their work as feminist .... It is my contention that -- whether unintentionally or lacking the language or cultural context to support a feminist idiom -- the artists in this exhibition contributed to the movement and development of feminism in art, if only by reinforcing two central tenets: the personal is political, and all representation is political.

To her credit and armed with some serious catalogue essays, Butler is trying to reexamine feminism in art beyond the well-worn doctrines. Nevertheless, the more one delves into the art selections themselves, the stranger it all gets, so let me offer some clarity.

I do not buy the idea that all women artists, even given the difficulties of achieving both critical and market recognition, are feminists by default. Nor do I think women artists who have profited careerwise by feminist actions qualify as feminist, either. But, to give "WACK!" a positive spin, let us say that the show is about the influence of feminism or which particular art efforts may have fed feminism, rather than about what I or anyone else deem to be the feminism that's politically correct.

One way to read "WACK!" is to go through the exhibition and try to determine what kind of feminist, if one at all, each artist is:

Feminist by virtue of both content and activism.

Feminist by virtue of activism.

Feminist by virtue of content.

Feminist by virtue of feminist support.

Feminist by virtue of being a woman artist.

Audrey Flack: Marilyn

Feminists By Virtue of Both Content and Activism

At the top of my list has to be artwork made by a feminist that embodies feminist principles or subject matter. Examples: Judy Chicago's Dinner Party in Brooklyn and much of the work preceding it; both the early geometric work by Miriam Schapiro at P.S.1 and her later "femmage" (not included). Certainly the performances, photo-pieces and sculpture of Ana Mendieta.

The realist painter Sylvia Sleigh was very active in the women's art gallery A.I.R. and other feminist causes. Her painting of the members of that fabled gallery certainly counts as feminist, as do her male nudes that turn the tables on the male gaze.

The still underappreciated Lynn Hershman is here represented by her brilliant "Roberta Breitmore Series," consisting of documentation of how she fully constructed and assumed another identity. Is this about the fact that women must go to great length to construct their personae, even to assume (metaphorically here) a false identity? I call this the Vertigo Effect -- after Kim Novak's masquerade in that Hitchcock masterpiece.

Now more than ever (with a simultaneous array of her photo-collages at the New Museum) it's clear that Martha Rosler is an artist to be reckoned with -- ghastly news images invade consumer-perfect living rooms and kitchens. Outside that picture window or even inside the perfect suburban home is the end of the world.

Nancy Spero is also finally getting her due -- in "WACK!," at the New Museum inaugural show, and in MoMA's current new-acquisitions survey. Never before have words, images, and politics been so movingly combined.

Joyce Kozloff? She is certainly also a feminist activist. Her work is a riff on Islamic patterning, which as far as I know was itself a male pursuit. On the other hand, patterning insofar as it is associated in our climes with the "merely decorative" has traditionally been considered women's work. Kozloff's work, at its best, is therefore quite sophisticated and destabilizing.

And I should also single out for special mention Audrey Flack's still glorious and still oddly disturbing photo-realist Marilyn.

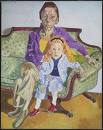

Alice Neel: Linda Nochlin and Daisy

Feminists by Default?

Skipping to the bottom of my list, two possible examples of feminists by default are Louise Bourgeois and Magdalena Abakanowicz. Bourgeois's bad Surrealism will always remain a mystery to me. Her work unfortunately suggests what some sexist Surrealists thought: a woman's proper role was as muse, not artist, because women don't really have a subconscious. Abakanowicz, on the other hand, is extremely talented. But isn't she a fiber artist and therefore a craft artist? No matter to me; in Artopia we have abolished such sexist and class-based discriminations.

The problem with both artists is that they went out of their way to assert they were not feminists. I guess a woman's word does not count. Or perhaps they have changed their minds?

Furthermore, the really wacky and to me always interesting Lee Lozano is also included, and there it is, plain as day, in one of her notebook pages on display: "Do not answer any of Lucy Lippard's phone calls." During the '70s, of course, Lippard was a highly visible feminist critic and well within Lozano's circle of friends. Lozano may have had other reasons for avoiding Lippard, yet she resisted the siren call. No sisterhood for her.

Expressionist portraitist Alice Neel certainly had feminist content when she painted pregnant women, and she gladly accepted the help of feminist artists who successfully petitioned for her first retrospective at the Whitney. But as a Communist (since the '20s), she could not declare herself a feminist since feminism was deemed a distraction from the struggle of the workers.

And our beloved Hannah Wilke is here too. We appreciate her snapped-together latex wall-pieces in the exhibition, but she's also represented by her unfortunate 1977 poster: Marxism and Art/Beware of Fascist Feminism. This reminded me of how anti-feminist, anti-sisterhood Wilke actually was. Her personal issue and only issue was that she felt her one-time artist paramour, who had become incredibly famous, had ripped her off artwise. She would not understand that perhaps he got away with it (if her claim were true) because he was a male artist. It was not that the political was personal or vice versa -- the mantras of olden days -- but that for Wilke the personal, alas, remained personal.

Lygia Clark: Structuring the Self, 1976-81

Is Feminism International?

"WACK!" attempts to be international, like "Global Feminism." Yet outside the Anglo-American and Northern European worlds, feminism is, as far as I can see, not a major practice. Racism and economic issues of various sorts remain more important. Or none of the above.

Lygia Clark from Brazil? Marta Minujin from Argentina? I admire both, but by no stretch of the imagination can they be considered feminists. Neither, to my knowledge, has directly addressed women's issues in their art or been an activist in feminist groups.

Nevertheless, please watch the Clark film in the little room devoted to some reconstructions of her astounding work.

Minujin's mattress hut on the second floor was the site of one of her performances on opening day. Clad in a white jumpsuit, wearing dark, dark sunglasses and using a bullhorn she demanded that those entering the mattress house had to know her name. Well, at least her first name. And as they were let in, they had to shout "art, art, art." Then the ice cello was delivered, and Minujin proceeded to "play" it, using a saw and a hammer, until it was destroyed. Was the cello a woman's body? Why was a gentleman inside the mattress house wrapping himself with blue tape like a mummy? I loved it. It was my kind of zany, but I leave it to you, dear reader, to figure out the feminist symbolism -- if there is any. In the meantime, I think the doctrinaire Surrealists were dead wrong. Women do have a subconscious, even Minujin.

What Can Be Done?

Feminism in its heyday involved collective action. Why has that been pushed to the background? Because collective action threatens the status quo? Women just might get the idea that the feminist effort needs to be rekindled. The Guerrilla Girls have never given up, but nowadays it looks like everyone else has.

Or was it just exhaustion? There are only so many meetings you can go to. No, I think what happened is that the commercial art world triumphed. Most collectors are conservatives. They have the money. Where did they get it? Therefore, there can be no political aesthetic. Male artists who express a political or dissident bent may be suppressed too, since the art market reasserts ego, profit, product. And the buck goes on.

FOR AN ARTOPIA ALERT FOR EACH NEW ENTRY

SEND YOUR REQUEST TO: perreault@aol.com

Other Worlds

The art world can too easily be seen as monolithic. What is bought and sold as art and makes a profit is the definition of art. Until quite recently, linear, evolutionary lineups were routinely used in exhibition catalogs and critical writings to provide a cursory justification of assumed historical outcomes. This reverse engineering was applied not only to formalist abstraction -- where the ploy was coined -- but could be jiggered for other styles, even the Dada/Surrealist one: Duchamp leads to Johns, Johns leads to....

But in Artopia, if asked to picture art history, we see a braid of many strands instead of any particular line concocted to verify sales or taste or objectify power. Furthermore, we see the reality of art as existing outside of objects. This rarification may be attained through objects, but this is not necessarily the case.

It may seem that the Art World Proper -- as opposed to the Art World Improper, which is synonymous with Artopia -- has become supremely product- and profit-centered, but we have hope. Slowly but surely we see the kinds of art once off the map or simply inadequately charted reappear. In truth, the Art World Proper is insatiable. Not only do curators constantly need new fodder to secure their reputations, graduate students have to come up with new subjects for their dissertations. Even art history can be ironic.

In spite of their anti-object, ephemeral profile, performative art forms such as Events, Actions, Street Works, and Performances are beginning to make the grade. No longer are museums so beholden to objects that nothing but stretched canvas and chunks of matter will suffice -- leaving craft as the embodiment of materiality, but letting it sneak into the panoply through deceptive labeling. George Ohr pots are in MoMA's Design collection. A Ronnie Horn thick rectangle of red glass is in Painting and Sculpture. Across the street, the Museum of the Arts and Design, formerly the American Craft Museum, now seems ashamed of the word craft.

And then there's Latin American art.

Does the Latin American Art World, like the craft world, overlap the Art World Proper, forming a parallel universe of discourse? Doesn't it also deserve to be another strand in the Big Braid?

Like U.S. and Canadian art, Latin American modernism was inspired by European developments. But aside from the important Mexican mural movement, not much of it represents a shift from the Euro-Modern.

More important, as the international (i.e., Euro-American) styles kept twisting and turning, from Pop to Minimalism and onward, it was difficult to really nationalize the changes of fashion.

By the early '60s, artists and their art traveled everywhere. Outside the Europe/Americas axis, other art stories and timelines fluoresced. For instance, are we sure what the new art of the last century looked like throughout Asia? But that's another story, as is rampant globalism -- how globalism differs from common internationalism.

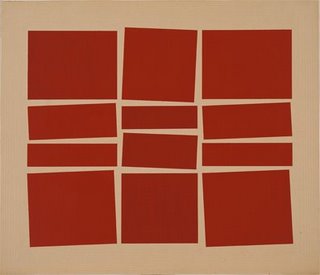

Hélio Oiticica, Metaesquema II,1958

Geo-Latino

The modest MoMA sampling of Latin American art -- "New Perspectives in Latin American Art, 1930-2006: Selections From a Decade of Acquisitions" (through February 25) -- favors abstract art, the best examples of which are the Neo-Concretism of the Brazilians Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark. And as the title might suggest to those attuned to such fine points, this cool exhibition does not include much art by Spanish-speaking artists north of the equator.

Most of the art displayed are works on paper, complemented by a few sculptures, of which Oiticica's Box Boilde 12, 1964-65, and two "variables" by Clark are outstanding. Viewers were originally urged to reach inside and experience the sand and cloth. Here the elegant presentations screams "Don't touch!" In fact, I had the feeling the nearby guard would arrest me if I tried.

Shown in the third-floor section of the exhibition, Clark's 1960 hinged Sundial, displayed in a vitrine, is also presented with no indication that it is a variable and can be changed at will. Only when we come upon her Poetic Shelter on the second floor are we informed that her Bichos (Critters) -- of which this piece is one of many -- are interactive.

We are not offered examples of the later, more important works of either artist: Oiticica's "Parangoles" (Capes) or Clark's over-the-top healing ceremonies. I searched for them on MoMA's website -- which, granted, gives you access to only 7,895 of 150,000 artworks-- but no "Parangoles" or healing works were in sight. I am not sure at this point if this is because examples were accessed prior to 1998 or there are real gaps in the collection.

(MoMA's "online collection" is free to all and is a great resource. Most entries include images. Teachers, you can assign curatorial exercises to your minions: For next week, select 30 images of artworks from the MoMA collection, according to your own scheme or theme.)

Are the late works of Oiticica and Clark so difficult to acquire? Or is it that Oiticica commits the sin of tropicalism. Tropicalia, sometimes called Tropicalismo, was a late-'60s, short-lived Brazilian art movement named after an Oiticica art work. Along with Oiticica, Clark and other artists, poets and musicians such as Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil joined the "cultural cannibalism" espoused. Central to the cause was the sly embrace and transcendence of Carmen Miranda-ism, enabling Rio's carioca revenge on Europe and North America -- before the group was shut down by the military government. The great Brazilian music stars Veloso and Gil went into exile.

Is it that late Clark is based on Brazilian shamanism, her rituals reportedly effective treatments for schizophrenia, and that she abandoned art to work with the mentally ill? A friend who experienced one of her rituals -- in which he was wrapped in cloth and pebbles placed on his eyelids -- told me he immediately began to hallucinate.

Although "New Perspectives" is a conservative survey of Latin American art, some concept-oriented works are included, for instance Brazilian Cildo Meireles' rubber-stamped cruzeiros from the '60s, but such works are rare. One hopes that the MoMA Latin American collection or future selections will open up a bit to go beyond what looks good to what is innovative and perhaps even a bit troublesome. It seems to be happening in other departments. Just take a look at curator Deborah Wye's current painting and sculpture collection selection called "Multiplex." David Hammons' hairy Rock Head! Jackie Windsor's Burnt Piece! Nancy Spero! Lynda Benglis!

In the meantime, to counteract the we-hope-unintended MoMA message that Latin American artists have uniformly sidestepped the political or the experimental, one must visit "Arte ≠ Vida: Actions by Artists of the Americas 1960-2000" at El Museo del Barrio, Fifth Avenue at 104th Street, to May 18.

On the Other Hand...

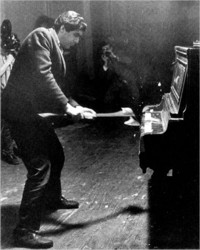

Rafael Ortiz, Destruction Ritual, 1967

Just as Alexandra Munroe's book Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky filled in the Japanese performative-art gap, "Arte ≠ Vida" will do the same for Latin American art. The catalog is supposed to be ready in May, and I advise you to order it now.

The panoply of excess charted by "Arte ≠ Vida" is the real deal. Through the lens of performative art forms we get a sense of the breadth and depth (and continued relevance) of the Latin avant-garde, from Argentina all the way north to Cuba and Puerto Rico and even Nueva York. Cuba-born Ana Mendieta is included, but is not in the MoMA show (although they have a great piece in their collection). Destruction artist Rafael Ortiz, the founder of El Museo, is shown in full force, destroying pianos -- there are even some piano guts on display. And the Brazilian Tunga is here too, represented by his photo of young twins joined by their long braids. This is an Artopia icon! And Marta Minujin's Parthenon of banned books. Other Artopia favorites represented: Rafael Ferrer from his performance/anti-form days, Alfredo Jaar, and Mexico's Francis Alÿs.

Full disclosure requires that I point out that although not Latino, I am represented in the El Museo exhibition. I gave El Museo a Xerox of the Street Works flyer I designed in 1969. The curator was interested in works by the Argentine Eduardo Costa -- coauthor of the famous Buenos Aires "Happening That Did Not Happen" hoax piece -- but who also spent many years in New York. In 1969, along with myself, Costa was one of the five organizers of the four New York Street Works actions that brought artists, poets, and even art critics out on the streets to perform artworks of their own devising. I am also represented in the exhibition by Tape Poems of that year, co-edited with Costa. You can therefore hear sound works by Vito Acconci, Hannah Weiner, Costa, myself, and others.

But how far do we want full disclosure to go? Do you need to know that Ana Mendieta was my graduate student in Iowa City? Do you need to know that I shook hands with Lygia Clark in New York in 1967, when the French critic Pierre Restany brought her around to meet people during the course her hand-shake piece? And that over the years I have routinely shared air-kisses with Marta Minujin?

In any case, curator Deborah Cullen's gigantic El Museo exhibition -- a true blockbuster -- sets the groundwork for a better picture of Latino art than MoMA's Good Neighbor template. First, "Latino" is a more generous, more adventurous and I think more accurate term for the New World Spanish/Portuguese-speaking world of art discourse. There are Latinos in the Caribbean. There are Latinos in our midst, in case you haven't noticed. This does not mean there are no differences, for example, between Mexican and Brazilian art. But we can worry about that later.

In Artopia, we have it both ways. It is not a question of either an all-embracing transnational art history or a series of particularized national histories. We deserve both, and more. The braid model does not preclude thematic internationalism; in fact, it requires it. A survey of world-wide performative art may now be possible, but this does not nix enriched, time-pegged surveys of all art forms in their raucous simultaneity and their interactive braidedness.

And, oh, by the way, a little bit of criticism. I think the title of the El Museo survey, although paradoxical and provocative, is misleading. Art Does Not Equal Life? In Artopia, at least, art does indeed equal life.

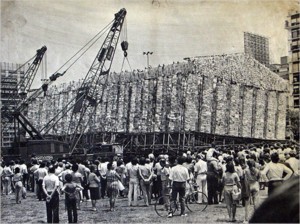

Marta Minujin, Parthenon, 1983, banned books wrapped in plastic

For an Automatic Artopia Alert to new postings contact: perreault@aol.com

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog