Artopia: March 2005 Archives

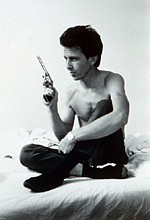

Larry Clark, "Untitled" (from Teenage Lust). Courtesy Luring Augustine Gallery.

What Photography Was

The battle for photography is pretty much over. If you can sell it as art, it's art. Of course, bigger is better because bigger has got to be more expensive. On the upside categories are unstable -- which infuriates the insecure. And since categories rule, who or what will be in charge when they are unreliable, vague or simply nonexistent?

We can, however, still squeeze a few puzzles out of photography in the form of questions never really answered (or questions answered with all the wrong responses). Walter Benjamin's age of mechanical reproduction is over, and we are already in the age of digital production. But, whether painted, captured by light triggering chemical reactions or on/off codes, an image is an image, right? Yes and no. We still can't escape the vehicle of presentation or the method of inscription. But those are for connoisseurs. It's the image that gets in the way of the materiality. Paradoxically, it's the image that's the issue or, rather, how we interpret that image. Poetry has snuck in through the peephole.

Two current exhibitions allow me to get closer to what I mean: "Diane Arbus: Revelations," at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fifth Ave. and 82nd St., to May 30) and "Larry Clark" at the International Center for Photograph (1122 Sixth Ave. at 43rd St., to May 5).

Diane Arbus: Young Man in Curlers at Home on West 20th Street, 1966.

The Arbus Argus

Freaks was a thing I photographed a lot. It was one of the first things I photographed and it had a terrific kind of excitement for me. I just used to adore them. I still do adore some of them. I don't quite mean they're my best friends but they made me feel a mixture of shame and awe. There's a quality of legend about freaks. Like a person in a fairy tale who stops you and demands that you answer a riddle. Most people go through life dreading they'll have a traumatic experience. Freaks were born with their trauma. They've already passed their test in life. They're aristocrats.- Diane Arbus.

We can find all sorts of precedents for Arbus' adventures in the abject. These, contrary to some superficial and dismissive readings of her images, do not include surrealism. Her bleak views of sideshow, sidewalk and backyard "freaks" do not contest reality; they expose it. Her friend, sculptor Nancy Grossman (quoted in Patricia Bosworth's Arbus biography), indicates that Arbus was interested in "how a photograph can capture the soul of a person, which is why photography is so sinister and mysterious." Souls? Arbus's subjects are symbols. But symbols of what?

Symbols are not signs; they are polyvalent. Ungainly nudists, forlorn triplets, her "others" are us, are her. They are as real as Walker Evans' Great Depression farmers. In other words, they are selected, posed, framed: caught. They are only as "real" as our response. Evans was hired to communicate poverty but, most agree, ended up communicating a kind of fake nobility. Arbus was not exactly sure what she wanted to communicate, but uncovered it as she went along: survival, danger, empathy, detachment.

The Arbus images are not as painful as they once seemed. We are used to transvestites and ugly couples in suburbia; we are accustomed to living rooms in Levittown and the Disneyland castle and to nearly empty movie theaters. Since her photos are all black-and-white and therefore in the past tense, we might easily see them in the light of when they were made. Would they have appeared in Vogue or Life Magazine? No way.

The only thing shocking about "Revelations" is when you see a photograph of someone you know. I did. It was of poet Gerard Malanga. So here's the problem does the context make him a freak too? What if the dominatrix in another picture had been of my Aunt Alice who unknown to me had had a secret career?

Larry Clark, "Billy Mann, 1968." From Tulsa.

A Needle in Your Eye

It was just kind of part of the scene because it was like organic and totally natural, and I wasn't thinking about doing anything with the photographs or showing them or doing a book or anything, it just wasn't in the consciousness until later. Then it became - well, I have all this stuff, it's like visual anthropology, you know, it should all be put together - Larry Clark ( from an interview in Pataphysics Magazine)

I am not sure it is fair to say that Larry Clark is a direct descendent of Arbus, but it will do for a start. His work too is shockingly subjective at first look. The images are apparently still raw enough that the N.Y. Times covered the exhibition in the Metro Section, not the Arts and Leisure Section, offering a reporter's piece about how the ICP was keeping a low profile in regard to the show and purposefully avoided government funding. The Metro Section does not go out in the national edition; just in case you didn't know, the Times sells more copies to non-New Yorkers than to those of us who brave the poverty, drama and glamour of the Big Apple. Why this type of coverage, and not a review or feature? There's a photo in the exhibition of a naked kid with a hard-on, aiming a gun at a bound girl. Also, in the images from Clark's career-making, self-published book Tulsa (1971), there's lots of shots of people shooting up speed.

Since teenage boy-flesh abounds in the photographs, is the fear of this art really a kind of homophobia? Looking at nakedness or evidence of arousal in public can be a problem. And although the artist is apparently not gay in the usual sense, his essay on Times Square boy hustlers (like his skateboarder pictures, like almost everything he has done) is heavy with male nostalgia, thinly disguised by social-issue, teen-problem concern.

In the so-called library rooms of the Arbus show you can read reproductions of pages from her notebooks, but not, as I recall, the last entry before her suicide, which according to Bosworth was simply: "The last supper." In the 1972 Aperture/MoMA Arbus monograph, you can assay her more structured stabs at explanation, such as: "I never have taken a picture I've intended. They're always better or worse."

In the Clark show, the artist's musings, including lists of drugs he has taken, are integral to the art. Like Weegee in his captions, Clark is a writer. There are, it's true, free-association texts, but what could be a better haiku than this for a print of "Billy Mann, 1968" (from Tulsa): "death is more perfect than life. dead 1970." Or the caption for images of a police informer being beaten: "every time I see you punk you're gonna get the same." Photography in books or in regulation-sized prints is closer to drawing and writing than it is to painting. The camera is a pen.

Like Arbus, Clark tells stories. Arbus crypto-narratives are single-image condensations of time. If she had lived, would she have tried her hand at movies? What kind of fables would they have been? Giants and transvestites? Nudists and wigs?

Rather than showing us iconic, stand-alone images, Clark presents image sequences. That he has become a filmmaker is an instructive natural development. Kids, 1995 (about Washington Square skateboarders and AIDS) and Bully, 1971 (based on a news story of youngsters who banded together to kill an enemy) are brilliant, upsetting films. In both, his camera eye lingers over teen flesh and teen drugs, but as in the photographs (I want to call them stills), these subjects are the bait. Before you know it you are asking yourself, why am I interested in this stuff? I don't have teenage children, thank God. I don't have a thing for boys, and any drugs I may have used in the deep, dark past had names and nicknames now unknown.

I personally find myself as fascinated by Clark's work as I once was with Arbus'. Could I, an art critic, also suffer, as both photographers do, from scopophilia? Here I am using Freud's definition: love of looking. Voyeurism is not a synonym, but a subset involving sexual gratification. The subject of voyeurism must not know, or at least must appear not to know, he or she is being watched. But most of the subjects of the photographs of Arbus and Clark know they are being looked at through the camera and will probably be looked at later by other people when the prints are exposed. To pose is to compose. Exhibitionism is the unacknowledged co-author of image culture.

Photography Is Not Reality

The mistake many make is to confuse photo images with reality. They are representations. They are constructed narratives; they are fictions. We, artists and viewers, if it is our bent, find the things that stand for or communicate what we want to express or, let's face it, what our unconscious may need to tell us or others.

Personally I am extremely reluctant to photograph people, even people I know. But if I were telling a story through images I wouldn't hesitate one minute to use friends or strangers as models. Is it so hard to believe that Arbus's so-called freaks or Clark's speed-freak teenagers are actors, or found images that stand-in for the photographer? Or that these freaks and speed-freaks are the subjects of voyeuristic fictions that allow unimpeded scopophilia? It is ultimately not what you are looking at that is important, but the looking itself.

Prague in the Fog

The Prague Balance Sheet

Travel is one of those mysteries I will never understand. Certain cities you know you will like ahead of time (Reykjavik, Rio); some will take you by surprise (Stockholm). Others, like Prague, are cities you know you should like but...

- The Czech language is made up entirely of consonants, yet is enough like the Polish of my grandmother to give me a craving for stuffed cabbage and a yearning for those light, feathery, Warsaw dumplings she made, my mother made, and I can make.

- After trying several beer-hall meals (we wanted real food, not fake Italian), Czech cooking seems to be based on delicious gravies sustained by the world's worst dumplings. Regulation beer-hall dumplings are hockey puck-size, Wonder Bread sponges. This bread dumpling, constructed of gluey boiled dough, sticks to the roof of your mouth forever. No amount of Pilsner will get it off. Perhaps the idea is that once in place, the permanent bread dumpling allows you to absorb flour-thickened and smoky-ham flavored pork, beef, or boar juice without the addition of superfluous carbs.

- Beer is the tap-water of Prague. In a beer hall that has been in operation since the 16th century, we saw one client down 10 steins of Pilsner as an aperitif. The entrée was a double order of sauerkraut and dumplings and...more beer. On his two trips to the gents', he did not once stagger. I think the dumplings were ballast.

- Because of theatrical lighting and poet and past president Václav Havel adding a "changing of the guards" ritual, the famous Prague Castle is now a blow-up of the Disneyland castle. At night, the empty, sloping alleyways reminded us more of stray scenes from the movie version of Mission Impossible than the Kafka or Meyrink atmosphere we expected. Where is Tom Cruise? No self-respecting Golem would find much lurking-space here.

- Aside from a sidewalk mosaic advertising a restaurant called the Ur Golema and Golem key-chains, Golem pop-up books and Golem drain-cleaners, I never saw the Golem.

The Other Side of My Tourist Balance Sheet

- The period Cubist railing in the stairwell of the Cubist Museum that now occupies The Black Madonna Department Store. The much praised building is only a mildly Cubist façade. Decorative facets alone do not a Cubist building make. Nevertheless, the Cubist Museum collection is worthy of note: it features Czech Cubism (1910-1919). Yes, there was such a thing. While New York was still not even struggling with Gothic skyscrapers, Prague was going wildly Cubist. Pave Jana's 1912 Cubist chair? Great. Stage-set designs and drawings of proposed buildings? Great. Paintings? Well-worth further investigation, because of the Czech addition of allegorical content and the idea that you grasp the essence of motion then freeze it in time. Czech Cubism is really Czech Futurism.

- Also a fine survey of the work of Cubist Vlastislav Hofman at the fully restored art nouveau Municipal House. Elsewhere bought a remake of his iconic Cubist ashtray, which according to the artist himself (as quoted in the printed insert) is "...a paring down and reduction of matter to unleash its essential internal forced making it possible to capture in abstract form its natural momentum." However, as some have already pointed out, Cubist furniture and so forth is clunky and generally had to have hollow tips to prevent it from being too heavy. Chairs with sharp edges, looking as if they are about to tip over; desks with dangerous drawers. But it can't be denied that these Czechs were the first and probably only ones to apply real Cubism -- as opposed to what later came to be called Art Deco -- to architecture and the decorative arts.

- The three-headlight 1947 Tetra automobile in the Museum of Industry.

- Lunch at the elegant Flambé Café. Aroma, aroma.

- A wonderful, ultramodernist Adolph Loos house in some ritzy neighborhood, passing it by on our way to a Korean restaurant.

- The wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling ceramic tiles of the Hotel Imperial Cafe, which redeems this museum of bad food. A giant compote of inedible day-old donuts is available for purchase to throw at people in your party or at other customers. The donuts, included with coffee, are, in fact, born inedible. I am not making the donut fight up. Our artist friend was actually splattered by donut jelly during one of these donut brawls.

- Virtually no cars downtown, so there are no parking lots taking up precious tourist sites. The trams and the subway are cheap and perfect. If a tram does not keep to schedule, it's the driver who gets fined.

- Except for high-end restaurants, food is half the price of New York. Supermarket prices are also half. Too bad Czech incomes are less thanhalf.

- Czech-language production of Mozart's Magic Flute, with English and German supertitles, in the perfect 1783 Estates TheaterwhereDon Giovanni debuted in 1787. "Praguers understand me," said Mozart. If you've seen Milos Forman's misinformed Amadeus, you'll recognize this neoclassical gem.

- My peak experience was not the Old Jewish Cemetery and Rabbi Loew's tombstone, although I too placed a pebble there. No, the cemetery merely reminded me of all the Jews who once lived in the Josef quarter -- in 1708, they were one quarter the population of Prague; before World War II, one fifth. Now there are, according to one guidebook, only 1,500 left. Rabbi Loew is the famous 15th century kabbalist (true) and creator of the Golem (legendary). In the nearby New-Old Synagogue (built in 950!) you can see the chair he sat in. That chair is where he is, not the tombstone, which he never touched and probably has been moved more than a few times, given the twelve-layer density of dead bodies in the cemetery.

The Appliances of Prague

I was in Prague not as a tourist -- although I am a tourist everywhere, even in New York -- but on assignment. I was there to write a piece for American Craft magazine about Karen LaMonte, an American living in Prague. Her exhibition of cast-glass clothing was at the Czech Museum of Fine Arts, in the cavelike cellar of a Romanesque building. The Czech Museum of Fine Arts is the Czech Smithsonian and stages art exhibitions in various historic buildings.

It was LaMonte and her partner, Steve Polaner (also American), who brought us to two Czech art openings. The first was at Futura, the P.S. 1 of Prague that opened in 2003 in Smichov just 10 minutes from the city center. It's in an old factory building with a warren of rooms and catacomb cellar spaces. Fortunately for me, "Insiders: The Unobtrusive Generation of the Late 1990s" (to August 5) surveyed your basic Prague postminimalism as exemplified by 11 artists. I did like the pencil wall-pieces by Jan Nálevka. Otherwise, Krištofa Kintera was the standout with his strange sex-toy "appliances" he had placed in various shop windows (1997-1998).

Except for the preponderance of unshaved male jaws (a Prague fad?), you could have squinted and thought you were at an opening in Williamsburg. My friends looked through the mob for Kintera, whom I wanted to meet, but came back to report that he was stressed out by some problem with his one-man show opening downtown the next night.

"We'll take you to a few openings," said our American friends, when we first arrived. No problem.

The opening downtown turned out to be of new work by Kintera in the very classy Galerie Jiri Svestka. The reason for Kintera's stress was immediately apparent: two of his mechanical pieces had for some unknown reason stopped operating. Judging by his look and his chain-smoking outside the gallery entrance, he was still pretty stressed, but the show was a success. I recognized a number of faces from the Futura opening the night before. Here, as in the museums there, were jolly retirement-age guards.

All of Kintera's newly minted sculptures, one to a room, involved sounds and movements, save I Can't Sleep (basically a wig in a sleeping bag from which creepy smoke emerged). All other works, like his early "Appliances," were sexually suggestive. The elegant and slightly threatening Something Electric was a wire plugged into a socket with the business end creating a repeatedly zapping electric arc. Children beware! It's Beginning was an electrified coconut knocking the floor. Unhappy Coincidence was a union of a computer mouse and a ski pole. There was also an electric bread knife with shoes humping a watermelon.

As an outsider trying to understand Kintera the Prague insider, I wondered if the great Czech animator/movie director Jan Svankmajer had been of any influence. Svankmajer's Otesanek (2000) is about a childless couple who adopt a curiously childlike and eventually voracious tree stump. His claymations and his stop-motion animations are classics. The one-minute Meat Love has been summarized as "Two piece of meat are cut, fall in love, have tricky meat sex and then are cooked up for our consumption." Like Czech Cubism, Czech Surrealism has yet to be fully explored.

Kristofa Kintera, I Can't Sleep, 2004

And the Results Are...

Would I visit again? Yes, but in warmer months, exclusive of what is now a tourist-invested summer. I would certainly go there for any kind of art project that came up. The Euro has not yet taken over, so it's cheap enough, and in spite of what I've written, it is charming enough. If you had to choose among Chicago, Toronto, Melbourne or Prague, which would it be? I'd choose Prague.

Nevertheless, on some deep somatic level I seem to have a problem with landlocked countries. The Czech Republic, if you take away Moravia, is what was once called Bohemia. We know from Shakespeare, who was being sarcastic when referring to a seacoast of Bohemia, that there is no seacoast. The U.N. lists 30 landlocked countries. But for some reason they leave out the Czech Republic, Tibet and Austria. I guess rivers count as seacoasts. But not in my book.

In case you were thinking of moving to Uzbekistan or Liechtenstein, please be informed that they are double-landlocked, i.e., entirely surrounded by other landlocked countries. Nowadays, one is always looking for options, but being doubly landlocked sounds too claustrophobic. I even have trouble with landlocked states like North and South Dakota. The unstated plus, of course, is that if you are landlocked, at least you can't be invaded by way of the sea.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog