An oddball item here, maybe more interesting to musicians than others. Or maybe not! Your call.

Of course, that might vary from performance to performance. This is one of the places I understand very well from a composer’s point of view. It’s where musical notation becomes a kind of poetry. You have something in mind, something not quite describable, something that lies beyond what notation can directly indicate. So you find a way of writing that suggests what you want — or, anyway, suggests it to you. What the people playing your music make of it is of course another question. Your poetic notation might not be clear to them at all.

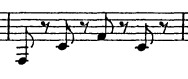

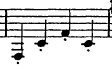

I think that’s the case here. A staccato dot, of course, tells us that a note should be shortened. But by how much? That’s an impressionistic thing, guided by knowledge of a composer’s style, and by pure feel. And normally it’s easy to handle that. But when you have two kinds of short notes in quick succession — eighth notes, whose length is precisely defined, and staccato quarters, whose length is a subjective thing — what do you do?

I’d love to be enlightened. Mahler’s throwing a curveball here.

Many thanks to the IMSLP – Petrucci Music Library, an invaluable (beyond invaluable) library of online, downloadable scores and parts. Took me just seconds to download the bassoon part in the symphony, and then take screenshots of the measures I wanted to quote. Petrucci’s scope is just about unbelievable. Any musician who wants access to classical scores needs to know this site!

I believe the notes ought to be approximately the same length; the difference would be in their evenness. The staccato quarter notes are hit hard, with a quick fade, while the eighth notes are played evenly, with no fade, but with a break between them. This has also to do with reverberation, a different matter for different types of instruments (I’m a flute player myself, and of course the strings will have a completely separate set of issues): the staccato notes should be allowed to reverberate, while the eighth notes should be followed by some attempt to stop the sound during the rests. Removing the fingers from all the keys will sometimes help, by dispersing the air. Yes, there is considerable difficulty doing this in such a quick passage, but our orchestras are filled with virtuosos these days (I say this with true admiration, not as sarcasm).

To get this, think like a composer. If you want particular sounds, stops, echoes, and so on, the notation is what you have to explain it to the players. Of course, I could be wrong, but that’s what makes sense to me.