Having written about the exhibition of John Singer Sargent’s watercolors at the Brooklyn Museum before it opened, I was curious to see it in the flesh. I went over the weekend, and am happy to say that it lives up to expectations. One surprise — the color of the walls behind the artworks, which was melon, verging on orange. But not the neon orange the Brooklyn Museum has used in its American art galleries. Rather, it’s a soft orange that you might find in a posh apartment on Park Ave. You can get a sense of it in my picture, at left.

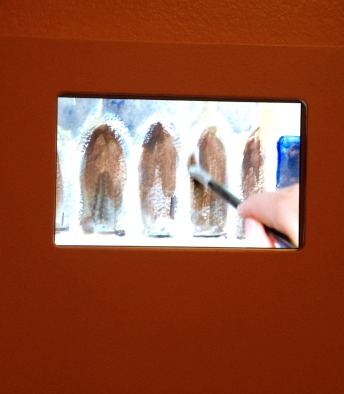

Having written about the exhibition of John Singer Sargent’s watercolors at the Brooklyn Museum before it opened, I was curious to see it in the flesh. I went over the weekend, and am happy to say that it lives up to expectations. One surprise — the color of the walls behind the artworks, which was melon, verging on orange. But not the neon orange the Brooklyn Museum has used in its American art galleries. Rather, it’s a soft orange that you might find in a posh apartment on Park Ave. You can get a sense of it in my picture, at left.

You can also see that the exhibition was quite crowded, which I was also pleased to see. Interestingly, it was more crowded than the El Anatsui exhibition, which also got rave reviews, including one from me on this blog. I was surprised, but the only conclusion I can draw is that Sargent has bigger name recognition. (In case you missed the news last week, the Brooklyn has acquired Black Block — which I show on the link above along with Red Block, which is owned by Eli Broad).

You can also see that the exhibition was quite crowded, which I was also pleased to see. Interestingly, it was more crowded than the El Anatsui exhibition, which also got rave reviews, including one from me on this blog. I was surprised, but the only conclusion I can draw is that Sargent has bigger name recognition. (In case you missed the news last week, the Brooklyn has acquired Black Block — which I show on the link above along with Red Block, which is owned by Eli Broad).

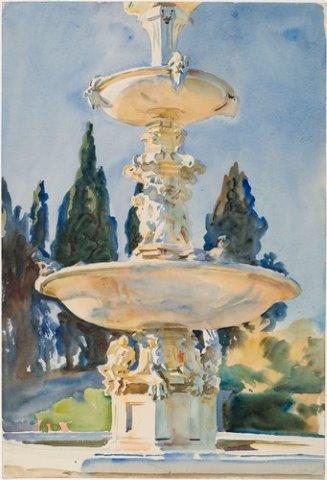

In my March piece on Sargent, I wrote:

In Brooklyn, the museum engaged a watercolorist to demonstrate six of Sargent’s watercolor techniques, including wax resist and scraping, in videos that will be shown on small monitors in the galleries.

Those videos were another item on my list of things to check in on. Were they obtrusive? Were people watching?

The answer to the first question is no, definitely not. The videos are quite small — maybe 6 by 4 inches, but I didn’t measure –and they are embedded in the wall, next to the painting they are illuminating. The mounting stand out from the wall by just an inch or so. They are also interesting, though they do take a little patience — the artist paints in real time, without being speeded up in post-production. I think they work.

I’ve posted a couple of examples here — the first, at top right, is drybrush painting. I did not see the wax-resist video, but one was out-of-order while I was there. Or maybe I just missed it. Those below show how the videos look in the galleries.

Photo Credits:  © Judith H. Dobrzynski