It’s widely recognized now that there’s no one art world, no one art market — and that perhaps is what underpins a couple of recent developments.

We’ll start with the news early this month that the Museum of Wisconsin Art in West Bend, WI., — which has existed for some 20 years — has a new building that will raise it profile and provide more space for showing art by residents of the state. Art writer Mary Louise Schumacher wrote about it in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel:

We’ll start with the news early this month that the Museum of Wisconsin Art in West Bend, WI., — which has existed for some 20 years — has a new building that will raise it profile and provide more space for showing art by residents of the state. Art writer Mary Louise Schumacher wrote about it in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel:

One of the goals of the museum’s new director and CEO, Laurie Winters, is to reconsider how to think about the art of the state and the role that a museum can play. With no major contemporary art institution in the region, save the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, she’s interested in finding ways to cultivate connections with contemporary artists, among other things, and has created an advisory board of working artists, curators and critics.

The JS has a wonderful slide show at the link above, which includes the photo I’ve copied here of Graeme Reid, director of exhibitions, amid an installation by Michael Meilahn.

Today, an article caught my eye about the groundbreaking for a museum in Daytona Beach, FL., that “will house the world’s most extensive collection of Florida art.” A couple named Cici and Hyatt Brown have donated the art they’ve amassed — some 2,600 works — over the years. It’s not contemporary, apparently: The local paper, The Ledger, says the earliest work dates to 1839 — a painting of the gates of St. Augustine, Fl. The Browns gave $13 million for the design and construction of the museum and have just said they will give $2 million to kick off an $8 million endowment campaign. Read more details here.

No. 3 on this list of unrelated developments is a blog post in Houston (ArtAttack on the Houston Press site) proposing that the city needs more museums, including one it would call the The Museum of Texas Art:

You would think we’ve got art covered what with the MFAH’s ever growing campus, Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Pearl Fincher Art Museum and the rest, not to mention the hundreds of galleries in the area, but on any given day, you’d be hard-pressed to find an exhibit that included anything that could be called Texas art.

We don’t mean just works by Texas artists or works created here in Texas. It takes a little bit more than that to qualify a painting or sculpture as Texas art. It takes an only-in-Texas vision and direct connection to other local painters and sculptors who either influenced or were influenced by the artist. The Texas Art Museum would have a collection of works by artists such as unique Lone Star state talents as Emma Richardson Cherry, considered one of the most forward thinking artists of her time.

Finally, the other day I received an email from the Cincinnati Art Museum noting that its Cincinnati Wing is about to celebrate its 10th anniversary. The museum says it was “one of the first art museums in the nation to dedicate permanent gallery space to a community’s art history.” It adds:

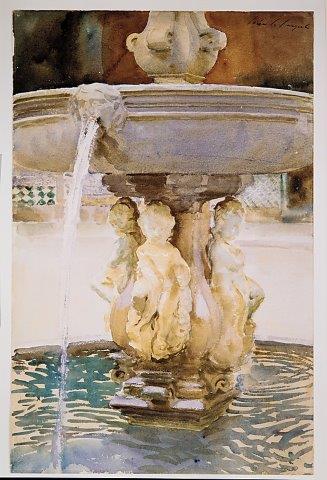

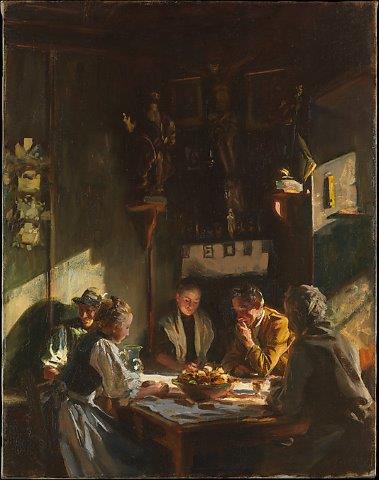

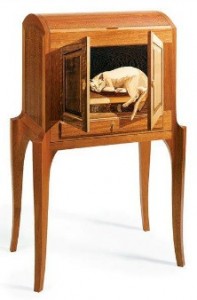

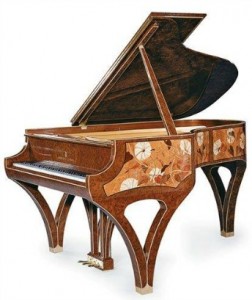

The 18,000 square feet of gallery space showcases more than 400 objects that represent art made by Cincinnati or Cincinnati trained artists, art depicting Cincinnati or Cincinnatians, or art commissioned for Cincinnati, including many works by American masters. The artists in the Cincinnati Wing include Frank Duveneck, a painter of international reputation; Hiram Powers, one of the nation’s finest sculptors; John H. Twachtman and Edward Potthast, regarded as two of the finest American Impressionists; Lilly Martin Spencer, the most celebrated female painter of her time; and decorative arts from the internationally renowned Rookwood Pottery.

I couldn’t find a link to the release online, sorry to say.

So there you have it — I align with the Houston blogger, Olivia Flores Alvarez, on this issue. Showing reginally made art is another way museums can differentiate themselves.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the Journal SentinelÂ