And, really, everywhere, doesn’t he?

American art historians sometimes self-divide into those who think that Winslow Homer was the greatest American artist of the 19th century and those who think Thomas Eakins was. I have always come down on the Homer side. So it was a real pleasure for me to travel to the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute a few weeks ago to see its summer exhibition, Winslow Homer: Making Art, Making History.

American art historians sometimes self-divide into those who think that Winslow Homer was the greatest American artist of the 19th century and those who think Thomas Eakins was. I have always come down on the Homer side. So it was a real pleasure for me to travel to the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute a few weeks ago to see its summer exhibition, Winslow Homer: Making Art, Making History.

Sterling Clark also came down on the Homer side. He called Homer one of the greatest artists of the 19th century — “with no qualifying “American” in that accolade,” as I write in my review, published in tomorrow’s Wall Street Journal. It’s headlined, Winslow Homer at the Clark Art Institute: The Makings of A Master. He bought more than 200 works by Homer — many were etchings, of course — and owned more works by Homer than any other artist. After his death, the Clark added more.

And, I believe, it has its eye on even more. Making Art, Making History is not a theme show; it’s an exhibition of the Clark’s collection. But the Clark has borrowed four watercolors and one painting from an unnamed private New York collector to fill in some gaps. And don’t they look great with all these others? Ah, the tried-and-true way to woo a donation!

I wish the Clark luck on that.

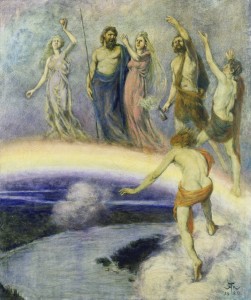

Here I’ve posted Homer’s marvelous West Point, Prout’s Neck — a painting critics panned when it was first shown – but if you like you can see his famous Undertow at that WSJ link. and four additional works — two paintings, two etchings — on my website.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the Clark