Last Friday, the Brooklyn Museum opened John Singer Sargent Watercolors – a landmark show, really, because it brings together a groups watercolors acquired by the Brooklyn Museum in 1909 and by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1912 for the first time. These early twentieth century watercolors together show how innovative Sargent was in this medium, which the museums assert was heretofore considered “tangential†to Sargent’s oeuvre and reputation — but shouldn’t be.

Last Friday, the Brooklyn Museum opened John Singer Sargent Watercolors – a landmark show, really, because it brings together a groups watercolors acquired by the Brooklyn Museum in 1909 and by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1912 for the first time. These early twentieth century watercolors together show how innovative Sargent was in this medium, which the museums assert was heretofore considered “tangential†to Sargent’s oeuvre and reputation — but shouldn’t be.

But last week, while at the Metropolitan Museum* to see Photography and the American Civil War (which, btw, is fascinating and fabulous), I ran into H. Barbara Weinberg, the American art curator there, who told me how those well-publicized purchases — by rival museums — led indirectly to the Met’s purchase of — Madame X. And some watercolors, too, of course.

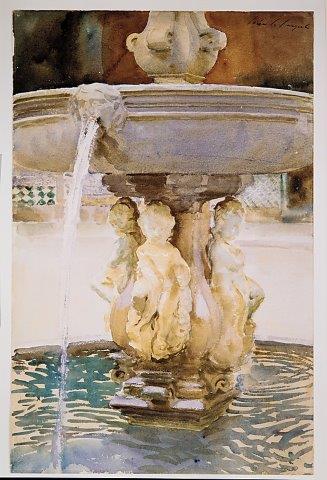

Here’s the tale: The Met, anxious to get its own cache of Sargent’s watercolors, approached Sargent in December, 1912, “with a plea for eight or ten watercolors,â€Â Weinberg wrote in the Spring 2000 Bulletin of the Met. Then “…He entered into an artful negotiation with the Metropolitan,†promising to sell one watercolor and to reserve “the best†of those he would do in the next year for the museum. The Met did agree to buy one, Spanish Fountain (at left), in January, 1913, but “Sargent’s ambivalence about the sheets that he had on hand and, later, his worries about transatlantic shipping during World War I, delayed the sale,†Weinberg wrote.

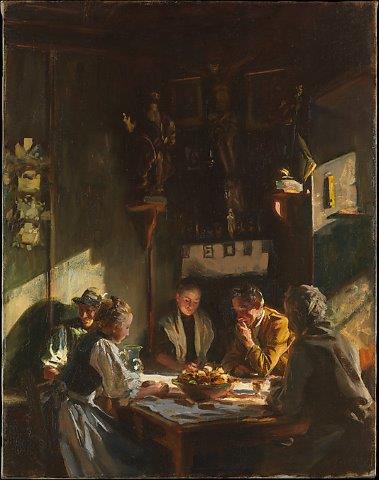

Two years later, Sargent picks up the ball again, and writes to the Met saying he was still trying to pick the best, and offering to include “the best oil picture I did in the Tyrol last year†for an additional sum. He enclosed a picture of Tyrolese Interior (at right) as museum-worthy, and sent it and 10 watercolors to the Met in December, 1915 — a year after these contacts began.

At the end of that month, the Met’s secretary, Henry W. Kent, wrote to Sargent with thanks. This time, it took Sargent less than two weeks to respond — with the proposal that the Met buy Madame X. In January, 1916, he wrote that the picture was on view at the San Francisco Exhibition and that “now that it is in America I rather feel inclined to let it stay there if a Museum should want it. I suppose it is the best thing that I have done. I would let the Metropolitan have it for £1,000.â€

At the end of that month, the Met’s secretary, Henry W. Kent, wrote to Sargent with thanks. This time, it took Sargent less than two weeks to respond — with the proposal that the Met buy Madame X. In January, 1916, he wrote that the picture was on view at the San Francisco Exhibition and that “now that it is in America I rather feel inclined to let it stay there if a Museum should want it. I suppose it is the best thing that I have done. I would let the Metropolitan have it for £1,000.â€

That sum, Weinberg said, was the equivalent of $4,762 at the time — about $100,000 in today’s dollars.

Kent wanted the painting — he’d been trying to buy it from Sargent for years. This time, he got it.

Why did Sargent have a change of heart? Virginie Gautreau had died in 1915 — remember that the painting had scandalized the public when it was first shown — but even so Sargent did not want her name to be attached to the painting. That’s why, when it was intalled at the Met for the first time in May, 1916, it was called Madame X.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the Met

*I consult to a Foundation that supports the Met