Several hours ago now, Donald J. Trump was elected the forty-fifth President of the United States. I haven’t slept in 36 hours. As the results of the election became clear, more than a few theater friends on my Facebook feed began to post the words: “The Great Work Beginsâ€â€”a reference to a phrase in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America and Angels in America, Part Two: Perestroika. Fueled by confusion and concern, and with a desire to spur myself and others to both reflection and action, I offer this post (a combination of new thoughts and those I’ve generated elsewhere over the past two years). I hope I can enjoin others to engage in a practical and hopeful conversation about where we go from here and the perhaps “painful progress†that we in the arts need to make.[1]

By the way, I am honored and delighted to announce that I recently began a 15-month fellowship as a (mostly virtual) Arts Blogger/Writer in Residence at the Thomas S. Kenan Institute at North Carolina School of the Arts. In the coming months you may see some of my Jumper posts syndicated on the Kenan website and vice versa.

At 10:58 pm Eastern—before the game-ending number of electoral votes had been reached and while Hillary Clinton still had at least a few pathways to 270—columnist Paul Krugman posted:

We still don’t know who will win the electoral college, although as I write this it looks—incredibly, horribly—as if the odds now favor Donald J. Trump. What we do know is that people like me, like most readers of the New York Times, truly didn’t understand the country we live in.

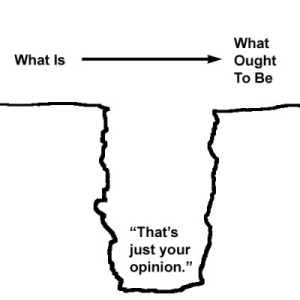

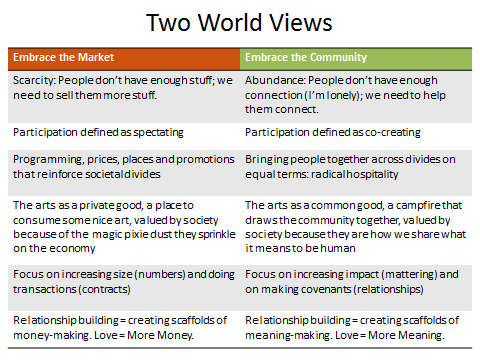

From where I stand, those working in nonprofit professional cultural organizations across the US—we in the so-called Creative Class—are, without a doubt, among those who did not understand our country, its culture, or its values. If we are shocked and outraged by the election results this only seems to prove the point. And this lack of understanding is disappointing given that art can be—arguably, should be—the way we share with one another what it means to be human (a powerful and democratizing notion I first encountered in Bill Sharpe’s wonderful monograph, Economies of Life: Patterns of Health and Wealth).

Looking at the programming on our stages it seems that many of us have existed inside a bubble, utterly out of touch with the Trump-supporting working poor in America, among many others.

How did this happen?

Virginia Woolf writes in her book, Three Guineas:

If people are highly successful in their professions they lose their senses. Sight goes. They have no time to look at pictures. Sound goes. They have no time to listen to music. Speech goes. They have no time for conversation. They lose their sense of proportion—the relations between one thing and another. Humanity goes.

This statement is hauntingly resonant when I think about the arts and culture sector in the US. The price of success has been the loss of our humanity as organizations. We appear to have lost our senses.

I came to this realization in June 2014 at a residential training with the organization Common Cause, which seeks to encourage NGOs and others working in the social sectors to join up to advance a set of common values in society—values like A World of Beauty, Social Justice, Equality, A Sense of Belonging, Broadmindedness, A Meaningful Life.[2] At the first gathering, when we went around a circle and talked about why we had chosen to come on the training, I said something to this effect:

I’m here because I don’t know if I can continue to work on behalf of the arts if the arts are only interested in advancing themselves.

I’m here because I’m worried about things like growing income inequality and suspect that growing income inequality may actually benefit the arts. And what are we going to do about that? I’m here because I’m worried about cultural divides and that the arts perpetuate them more than they help to bridge them.

I believe the arts could be a force for good, but I believe we will need to change as leaders, and as organizations, in relationship to our communities, for them to be so.

I was despairing about my life working in the arts when I spoke these words and I felt that same despair this morning in the aftermath of the election. But it is incumbent upon us to move on from sorrow as there is important work to be done. Earlier this year, New York Times columnist David Brooks argued in this article that there are forces coursing through all modern societies that, while liberating for the individual, are challenging to social cohesion—meaning the willingness of members of a society to cooperate with each other in order to survive and prosper together.

Friends, this is our crisis today. And we need to wake up to it.

Do we really want to be #strongertogether? If so, who better than the arts to help repair the divides in our country? Who better than we to contribute to the fostering of social cohesion? And do we understand that, without this, many other aspects of society—including the economy—will continue to break down?

So how do we begin again?

Honestly, it feels impossible at the moment. Nonetheless, I’d like to suggest that we might start by borrowing a page out of the play book of a colleague in the UK, Andrew McIntyre. For the past few years Andrew has been leading workshops in which he guides arts organizations to write manifestos. He justifies this work saying:

If you just want to organize the world a little more efficiently, you’ll get away with just a business plan. But if you want to change the world, leave your artistic mark, make a cultural impact or have ever used the word transform, then nothing short of a manifesto will do. Manifestos are open letters of intent that are fundamental and defining. They terminate the past and create a vision of new worlds. They demand attention, inspire and galvanize communities around us and knowingly antagonize others. They provoke action.

As citizens of a country that feels dangerously unstable, incoherent, unmoored, precarious, and divided, I suggest we begin by tearing up the generally lifeless and useless corporate mission statements that currently guide many of our organizations. In their place let us compose manifestos grounded in the reality of the present moment. Here are some questions to get you started:

What are you laboring for that transcends your organization and position within it—what values, goals, or progress in the world? Indeed, what are we laboring for collectively? Do we have a common cause?

It’s a small way to begin.

In his 2014 keynote address for a reunion of Asian American alumni at Yale, Vijay Ayer remarked:

Now that I am hanging my hat each week at that other centuries-old corporation of higher learning, just up the road in Cambridge, I am more and more mindful of what the British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare has called complicity with excess.

And as we continue to consider, construct and develop our trajectories as Americans, I am also constantly mindful of what it means to be complicit with a system like this country, with all of its structural inequalities, its patterns of domination, and its ghastly histories of slavery and violence.

Many of us are here because we’ve become successful in that very context. … Whether you attribute it to some mysterious triple package or to your own Horatio Alger story, to succeed in America is, somehow, to be complicit with the idea of America—which means that at some level you’ve made peace with its rather ugly past.

As we write our manifestos, let us do so cognizant of the possibility that the success of our institutions may be related to decades of “complicity with excess†and let us also temper any tendencies toward self-righteousness, bearing in mind the words of American feminist, author, speaker, and social and political activist, Courtney Martin.[3] Perhaps, she says,

…our charge is not to save the world after all, it is to live in it, flawed and fierce, loving and humble.

If we are to fulfill our highest purposes as communal organizations—places where art can provide a way for people to share with one another what it means to be human—then it seems that we arts workers will need to let go of the notion upon which many nonprofit professional cultural organizations were founded: that we exist, essentially, to save the world with art (and, quite often, with Western European Bourgeois Art, specifically). Instead, it seems that our first charge is to live fully in our tragically divided country and participate fully in our tragically broken democracy. Fleeing physically, mentally, emotionally, or spiritually is to deny both our culpability and power to make a difference. (And, yes, in case you are wondering, I’m planning to move back to the US when I finish my dissertation.)

It’s time to walk out into our communities, with our senses wide open, and absorb “the relations between one thing and another.â€

It’s time to find our humanity and help others to find theirs.

***

[1] “The World only spins forward. We will be citizens. […] More Life. The Great Work Begins.” “Painful progress†is also from Kushner’s Angels in America, Part Two: Peristroika: “In this world, there is a kind of painful progress. Longing for what we’ve left behind, and dreaming ahead.â€

[2] These values are taken from the research of Shalom Schwartz. You can read more about this at http://valuesandframes.org/handbook/

[3] From her book, Do It Anyway, as cited by Krista Tippet in the session: Parker Palmer and Courtney Martin – The Inner Life of Rebellion. http://www.onbeing.org/program/parker-palmer-and-courtney-martin-the-inner-life-of-rebellion/7122

[contextly_auto_sidebar]

![By Pink Sherbet Photography from USA [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Common](http://www.artsjournal.com/jumper/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Free_coiled_tape_measure_healthy_living_stock_photo_Creative_Commons_3209939998-200x300.jpg)