In last week’s post I wrote about a lecture by Polly Carl on the first half of Elaine Scarry’s monograph on beauty, which focuses on the relationship between beauty and truth. This week’s post takes as a starting point Polly’s lecture on the second half of Scarry’s book, which focuses on the relationship between beauty and justice. From there, it explores the importance of beauty in a democratic society.

In last week’s post I wrote about a lecture by Polly Carl on the first half of Elaine Scarry’s monograph on beauty, which focuses on the relationship between beauty and truth. This week’s post takes as a starting point Polly’s lecture on the second half of Scarry’s book, which focuses on the relationship between beauty and justice. From there, it explores the importance of beauty in a democratic society.

How beauty presses us toward justice

Polly began her lecture by explaining that there are two enduring criticisms of beauty that Scarry seeks to counter.

(1)  The first criticism is that beauty distracts us from social wrongs. Scarry counters with the argument that seeing something beautiful wakes us up and inspires us to turn our attention to others. She writes (on p. 81) of Plato’s notion that we move from “eros,†in which we are seized by the beauty of one person, to “caritas,†in which our care is extended to all people.

(2)  The second criticism of beauty is that the viewer’s gaze is destructive to the object or person. Scarry counters this idea with the argument that when we pay attention to another being, both viewer and object come alive. She writes (on p. 90), Beauty is, then, a compact, or contract between the beautiful being (a person or thing) and the perceiver. As the beautiful being confers on the perceiver the gift of life, so the perceiver confers on the beautiful being the gift of life. [1]

Scarry also finds that these two enduring criticisms of beauty are fundamentally contradictory. The first assumes that if our ‘gaze’ could just be shifted away from beauty toward some neglected object our attention would bring the wronged object remedy; the second assumes that sustained attention can never be beneficial and always brings suffering to the object.

Scarry addresses these two criticisms as the first step in her thesis that:

… beauty, far from contributing to social injustice in either of the two ways it stands accused, or even remaining neutral to injustice as an innocent bystander, actually assists us in the work of addressing injustice …

Below is a video of a lecture in which Scarry outines the key arguments about beauty and social justice from her book. My points below are drawn from this videotaped lecture.

Scarry prefaces her talk by noting that beauty and justice share the same synonym—fairness—and that, etymologically, the word that best describes the opposite of both beauty and justice is injury. Scarry then outlines three sites in which beauty presses us toward justice.

I. Beauty in the object itself.

The attributes of the beautiful object have parallel attributes in justice. For example, the symmetry in a flower, or a poem, or Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, models the concept of justice, which is defined by John Rawls as “a symmetry of everyone’s relations to each other.â€

II. The immediate response to beauty in the viewer.

In The Sovereignty of Good Iris Murdoch’s asks, “How can we make ourselves better?†She answers: In a secular age, beauty is the “most obvious thing in our surroundings†to help us “move in the direction of unselfishness, objectivity, and realism.â€[2] Murdoch observes that when a beautiful object hooks our attention it draws us out of our normal state of selfish absorption and shifts our attention to the world around us. She calls this process unselfing.Â

Scarry’s term for this unselfing is opiated adjacency, by which she means that beauty reveals to us that we are not the center of the universe, but that the experience of ‘sitting on the sidelines’ is pleasurable. Scarry argues that while many things can bring us pleasure and many things can knock us into the margins, beauty may be the only thing that does both. When we are transfixed by the beautiful object, it inspires in us a desire to locate truth (discussed in last week’s post) and advance justice.

III. In the aftermath, when beauty gives rise to the act of creation.

This is the idea of replication or unceasing begetting (also discussed in  last week’s post). When we see beauty we are drawn to create more beauty: We write a poem, take a photograph, compose a song, bake a cake, plant a garden, draft a legal treatise, share a beautiful object with another. This unceasing begetting inevitably leads to the distribution of more beauty in the world.

The importance of beauty in a democratic society

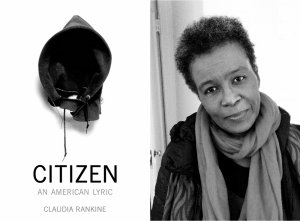

A couple of weeks after Polly’s lecture I asked the students to read the first 55 pages (sections I-III) of Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric. My aim was to explore the importance of beauty (in particlar, art and artists) in a democratic society. As President John F. Kennedy spoke in a 1963 speech honoring the life of poet Robert Frost:

If sometimes our great artists have been the most critical of our society, it is because their sensitivity and their concern for justice, which must motivate any true artist, makes him aware that our Nation falls short of its highest potential. I see little of more importance to the future of our country and our civilization than full recognition of the place of the artist. … Artists are not engineers of the soul. It may be different elsewhere. But democratic society–in it, the highest duty of the writer, the composer, the artist is to remain true to himself and to let the chips fall where they may. In serving his vision of the truth, the artist best serves his nation.

In her beautiful book-length poem, interspersed with images, Claudia Rankine raises our consciousness of everyday acts of racism. Two of the sections the students read are, essentially, a record of injurious remarks that Rankine has taken in and a recounting of the anger that has built up over time in response to these humiliations. She gives testimony to these everday shocks to the system as in a diary or logbook: one per page, page upon page.  Here are two pages:

Page 12

Because of your elite status from a year’s worth of travel, you have already settled into your window seat on United Airlines, when a girl and her mother arrive at your row. The girl, looking over at you, tells her mother, these are our seats, but this is not what I expected. The mother’s response is barely audible—I see, she says. I’ll sit in the middle.

Page 43

When a woman you work with calls you by the name of another woman you work with, it is too much of a cliché not to laugh out loud with the friend beside you who says, oh no she didn’t. Still, in the end, who cares? She had a fifty-fifty chance of getting it right.

Yes, and in your mail the apology note appears referring to “our mistake.†Apparently your own invisibility is the real problem causing her confusion. This is how the apparatus she propels you into begins to multiply its meaning.

What did you say?

In addition to exploring the meaning and impact of particular passages, I prompted discussion among the students with a number of questions:

- What is Rankine’s goal with this work?

- Does it turn you off or draw you in? Why?

- Do you recognize this everyday racism she’s talking about?

- How does reading this poem make you feel?

- Have you witnessed or experienced or participated in these types of injuries?

- Where else and how else do we dehumanize people?

- Have you ever felt injured in this way?

Dehumanization explored on a visit to the Chazen Museum of Art

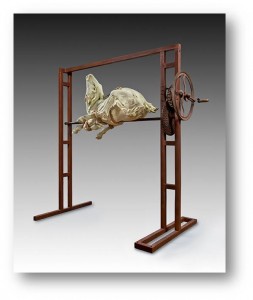

The day we discussed Rankine we also spent an hour at Chazen Museum of Art viewing four artworks, selected by the docents. Two were the sculptures Humiliation by Design by Beth Cavener Stichter and Black Jack, by Inigo Manglano-Ovalle.

With the docents, we observed the threatening angle and missile-like tip of Black Jack, as well as the work’s cold, dark, impenetrable surface. We interpreted it to be about asserting power over another. It brought to mind notions of war games and star wars. We also noted that the large globes of the jack reflect back to the viewer a distorted self image. In contrast, Cavener’s goat (evidently based on someone she knows, as many of her works are) embodies the state of being systematically disgraced, shamed, tortured, or disempowered by another. We were at first repelled by and then drawn into this sculpture. The students were invited to spend more time with the work they found most interesting. A majority decided to revisit the goat sculpture.

After the Chazen visit, sculptor Paul Sacaridiz (who is currently chair of the Art Department at UW-Madison) talked about his work and process (more on that in another post); however, he also took a few moments at the top of his talk to speak to the importance of beauty (and, in particular, artists and art) in a democratic society. He commented to the students, “As graduates of a university, you have an obligation to look at the world critically and to question things. […] Art is a way of understanding the world; and there is no better way of comprehending things that are ambiguous or contradictory or complex than by going to see art. […] If you spend time with art you begin to develop this understanding.”

Portfolio Assignment:Â Injury Documented

While the students’ portfolios are intended primarily as catalogues of their experiences of the beautiful, in week 8 I gave them the exercise: Creatively document a way in which you see people being dehumanized in your world (small world or big world). Many documented ways in which the homeless, the physically different, those with mental illness, the LGBT community, and ethnic minorities are routinely dehumanized. A few also captured the everyday harms we inflict upon each other in our day-to-day social interactions on social media and in person. A good example of the latter is this poem by student, Michelle Croak. I end this post by sharing it with you.

It is saying “Hello!†on the street

and a negative thing behind closed doors.

It is asking your roommate how their day was

and checking your email while they answer.

It is telling someone you are SO sorry

and feeling nothing but regret for saying the “S word.â€

What is it?It is telling someone “We should catch up!â€

without following up.

It is saying “I love youâ€

without action to back it up.

It is offering to cover someone’s portion of the check

without bringing out your credit card.

What is it?It is unconditional love

but including all the conditions.

It is being Facebook Official

but refusing to hold hands around others.

It is saying everyone is equal

but not including everyone.

What is it?What is it?

Dishonest. Insincere. Artificial. Untruthful. Disingenuous.

Dehumanizing.

Do we need a single word, a single phrase for all of these actions?

Do you see yourself in them? Do you see others?

Have you witnessed them and said nothing?

Then the next time I ask you, “What is it?â€

You only need one word to answer.

Me.

***

[1] While not referenced by Scarry, for more on this notion I recommend the recent New York Times article, Being There: Heidegger and Why Our Presence Matters. Hat tip to my friend, Greg Conniff, for drawing this article to my attention.

[2]Â Murdoch, I. (1991). The sovereignty of good. London: Routledge. As cited in Winston 2006, p. 285.