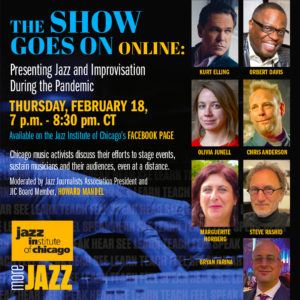

Chicago presenters of jazz and new music, and journalists from Madrid to the Bay Area, vocalist Kurt Elling, trumpeter Orbert Davis and pianist Lafayette Gilchrist discussed how they’ve transcended coronavirus-restrictions on live performances with innovative methods to sustain their communities of musicians and listeners, as well as their own enterprises were in two Zoom panels […]

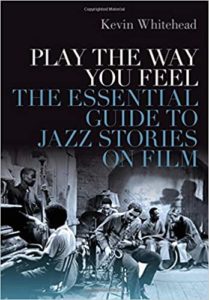

Love movies, jazz, and thinking about them? A treat

Movies, jazz and reading remain my favorite solitary diversions, and Fresh Air critic Kevin Whitehead enables immersion in all three with Play The Way You Feel: The Essential Guide to Jazz Stories on Film, his entertaining, provocative, deeply informed look at some 120 flicks and a handful of tv shows relating tales that mirror or […]

Four months of jazz adaptation, resilience, response to epidemic

In early March – only four months ago – I flew between two of the largest U.S. airports, O’Hare and JFK, to visit New York City. I stayed in an East Village apt. with my daughter and a nephew crashing on her couch. We ate barbecue at a well-attended Jazz Standard performance by drummer Dafnis […]

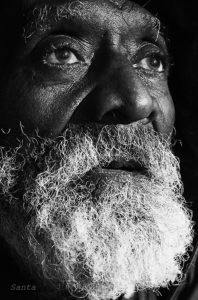

Revered jazz elders, deceased: portraits by Sánta István Csaba

As a generation of jazz elders leaves our world — some hastened by the pandemic — their faces as photographed by Sánta István Csaba become even more luminous, haunting, iconic. Originally from Transylvania and currently living in Turin, the northern Italian area with heaviest covid-19 infections, Sánta reports that he is healthy, employed at the […]

Future Jazz past: Hal Willner, circa 1992

The death of funny, smart, idiosyncratic, unique music producer Hal Willner at age 64 saddens me. We were East Village neighbors in the go-go ’90s, flush with ideas to try in the future. Here’s my entry about him from Future Jazz (Oxford U Press, 1999). CONCEPT PRODUCER AS VISIONARY “My projects happen mostly by accident,” […]

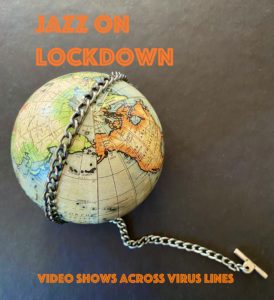

Jazz vs. lockdown: Blogs w/ vid clips defy virus muting musicians

Jazz doesn’t want to stay home and chill — so members of the Jazz Journalists Association launched on Monday, 3/15/2020, JazzOnLockdown: Hear It Here, a series of curated v-logs featuring performance videos of musicians whose gigs have been postponed or cancelled due to coronavirus concerns. The initial JOL post, by Madrid blogger Mirian Arbalejo (of […]

Mardi Gras’ lewd Krewe, Marc Pokempner’s photos

Satirical, scatalogical New Orleans parade floats by Krewe du Vieux Carré, via photojournalist Marc PoKempner

Chicago Jazz fest images, echoes

The 41st annual Chicago Jazz Festival has come and gone, as I reported for DownBeat.com in quick turnaround. I stand by my lead that the music was epic — cf. Marc PoKempner‘s beautiful image of the Art Ensemble of Chicago at Pritzker Pavillion, facing east towards Mecca just before their African percussion-driven orchestral set. And […]

Transcending Toxic Times with street poetry & music

My DownBeat article about Transcending Toxic Times, the compulsively listenable, critically political album by the Last Poets produced by electric bassist/composer Jamaaladeen Tacuma, includes a lot of quotes from my interviews with him and poet Abiudon Oyewale. I reproduced some of the searing imagery/lyrics on the recording, and provided background on how these men have […]

Dr. John, Back in the Day and Blindfolded

Dr. John the Night Tripper — Mac Rebbanack, New Orleans’ musical fabulist, dead June 6 at age 77 — dazzled me at one of the first rock shows I recall attending, at Chicago’s Aragon Ballroom circa 1969. I was then enthralled by Gris-gris, his murky, obscure and carnivalesque debut album, having never heard anything like […]

Black Chicago music fest producers: The costs of “free”

Chicago offers, surprisingly enough, many opportunities to catch exciting, accomplished and emerging music across genres, with oodles of concerts free of charge, meaning they have to funded by others than attendees. Our extraordinary summer events season launched last weekend with the city-sponsored, all-free 34th Annual Chicago Gospel Festival in Millennium Park and I’m psyched for […]

Digging Our Roots videos, speakers inspire engagement

Musicians and journos with insights into historic hits can offer curious audiences low-cost interactive experiences that bond most everybody present, like any successful performance.

Guitarist Kenny Burrell shouldn’t be in trouble. But he is.

Guitarist Kenny Burrell — since the 1950s a prominent, popular and influential jazz innovator, recording ace, bandleader and esteemed educator (prof and director of Jazz Studies at UCLA) — at age 87 is suffering grievous financial calamity due to health care costs and multiple frauds. His plight is candidly detailed by his wife Katherine at […]