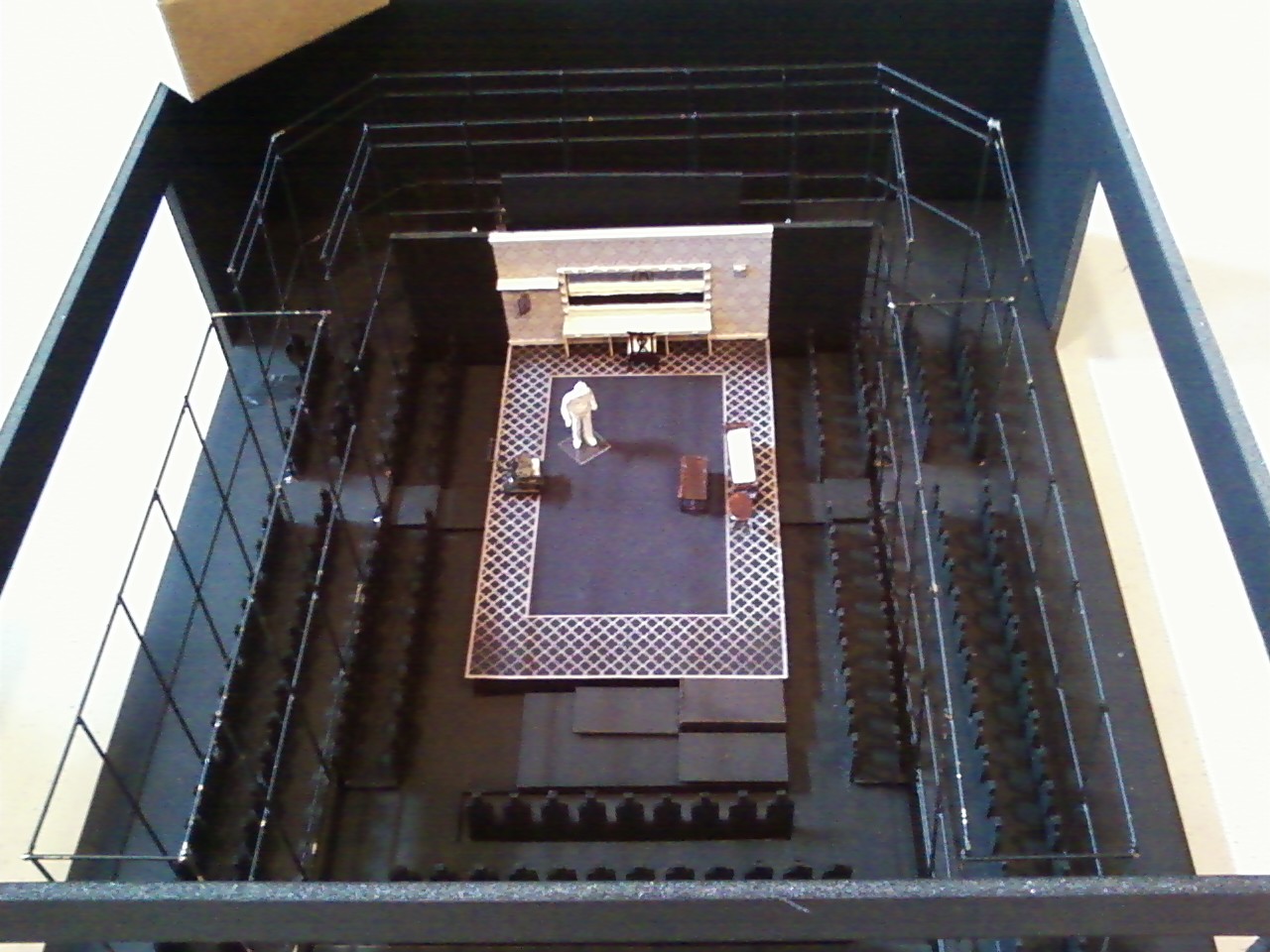

John Douglas Thompson, Gordon Edelstein, and I have a week’s worth of rehearsals for Satchmo at the Waldorf under our belts. We’re very pleased with our progress to date. Not only is most of the script now staged, but Lee Savage’s set (the model for which is pictured above) and Ilona Somogyi’s costumes are under construction at Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, and I’ve written three new speeches since we went to work on Tuesday.

John Douglas Thompson, Gordon Edelstein, and I have a week’s worth of rehearsals for Satchmo at the Waldorf under our belts. We’re very pleased with our progress to date. Not only is most of the script now staged, but Lee Savage’s set (the model for which is pictured above) and Ilona Somogyi’s costumes are under construction at Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, and I’ve written three new speeches since we went to work on Tuesday.

Mrs. T and I celebrated last night by watching Mike Leigh’s Topsy-Turvy, the greatest backstage movie ever made. Now that I’ve collaborated on two operas and a play, I understand better than ever before exactly how good it is. As I wrote in a 2011 “Sightings” column about Gilbert and Sullivan, Topsy-Turvy is

a deeply knowing fictional study of how a theatrical production takes shape….We visit the office of Richard D’Oyly Carte and notice with surprise that he has a phone on his desk; we dine in Victorian restaurants, sit in Victorian parlors, go backstage at the Savoy Theatre and watch a prop man shake a piece of sheet metal to simulate the sound of thunder. Detail is piled on imaginatively re-created detail, and by film’s end you feel as though you’ve taken a stroll through a vanished world.

Whenever I watch Topsy-Turvy, I’m reminded of how much I love being immersed in the endlessly complex process of rehearsing a show. You feel as though you’ve slipped through a hidden door and vanished into a secret world, a parallel universe populated by variously eccentric geniuses who are totally devoted to lifting your script off the page and bringing it to life. I treasure every minute I spend in their company, and I learn a hundred priceless things each time we assemble in the rehearsal room.

Whenever I watch Topsy-Turvy, I’m reminded of how much I love being immersed in the endlessly complex process of rehearsing a show. You feel as though you’ve slipped through a hidden door and vanished into a secret world, a parallel universe populated by variously eccentric geniuses who are totally devoted to lifting your script off the page and bringing it to life. I treasure every minute I spend in their company, and I learn a hundred priceless things each time we assemble in the rehearsal room.

Tonight I’ll be watching a preview of Into the Woods in Central Park, but I plan to drive back to Massachusetts as soon as it’s over. I’ve got an eleven o’clock call in Lenox tomorrow morning, and I can’t wait to rejoin my new friends and resume the ecstatically hard work of putting Satchmo at the Waldorf on stage.

When the spotlight goes out on theatrical fame, it leaves behind impenetrable darkness. A century ago J.M. Barrie was as well known as George Bernard Shaw or Henrik Ibsen. Today “Peter Pan” is the only one of his many plays that continues to be performed in this country, and most Americans think that Jerome Robbins wrote it. Were it not for Mr. Robbins’ much-loved musical-comedy version of the 1904 stage fantasy about a plucky boy who refused to grow up, Barrie would be nothing more than a footnote to the history of Vicwardian theater. Might he be due for a second look? Gus Kaikkonen, the artistic director of the Peterborough Players, thinks so, for his company is currently performing “The Admirable Crichton,” a once-famous Barrie comedy that disappeared from the American stage decades ago–and judging by Mr. Kaikkonen’s brilliantly effective production, it’s a not-so-minor masterpiece…

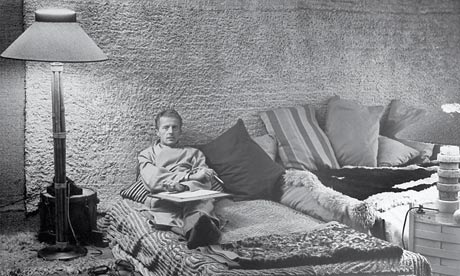

When the spotlight goes out on theatrical fame, it leaves behind impenetrable darkness. A century ago J.M. Barrie was as well known as George Bernard Shaw or Henrik Ibsen. Today “Peter Pan” is the only one of his many plays that continues to be performed in this country, and most Americans think that Jerome Robbins wrote it. Were it not for Mr. Robbins’ much-loved musical-comedy version of the 1904 stage fantasy about a plucky boy who refused to grow up, Barrie would be nothing more than a footnote to the history of Vicwardian theater. Might he be due for a second look? Gus Kaikkonen, the artistic director of the Peterborough Players, thinks so, for his company is currently performing “The Admirable Crichton,” a once-famous Barrie comedy that disappeared from the American stage decades ago–and judging by Mr. Kaikkonen’s brilliantly effective production, it’s a not-so-minor masterpiece… Music is even more central to “The Glass Menagerie,” Tennessee Williams’ first stage success, which was scored by Paul Bowles in three days for a flat fee of $50. I doubt that so small a sum has ever been spent to better effect by a producer. A minute after the curtain goes up, Tom Wingfield, the narrator, speaks these words: “The play is memory. Being a memory play, it is dimly lighted, it is sentimental, it is not realistic. In memory everything seems to happen to music.” Underneath his speech you hear a distant, delicate musical phrase that sounds as fragile as spun sugar. Variations on this phrase are heard at key moments throughout the play, usually in connection with the collection of glass animals owned by Laura, Tom’s shy sister, who fears life and lives in a world of dreams….

Music is even more central to “The Glass Menagerie,” Tennessee Williams’ first stage success, which was scored by Paul Bowles in three days for a flat fee of $50. I doubt that so small a sum has ever been spent to better effect by a producer. A minute after the curtain goes up, Tom Wingfield, the narrator, speaks these words: “The play is memory. Being a memory play, it is dimly lighted, it is sentimental, it is not realistic. In memory everything seems to happen to music.” Underneath his speech you hear a distant, delicate musical phrase that sounds as fragile as spun sugar. Variations on this phrase are heard at key moments throughout the play, usually in connection with the collection of glass animals owned by Laura, Tom’s shy sister, who fears life and lives in a world of dreams….