Author (#9)October 2003 Archives

First Sight: The Performance

An extraordinary dancer doesn't need to be discovered. He's apparent. I had my first, startling, sight of Danny Tidwell last spring in one of the Guggenheim Museum’s show-and-tell Works & Process programs. The subject of the evening was ballet competitions. American Ballet Theatre, which harbors many a medalist, sent a bunch of them out to perform their winning numbers and then, without pause for breath, to chat about the competition phenomenon with John Meehan. Meehan heads the ABT Studio Company—a dozen hand-picked young hopefuls serving a critical apprenticeship. Tidwell, one of these aspirants, opened the show in the Corsaire pas de deux, offering a thrilling glimpse of nascent stardom.

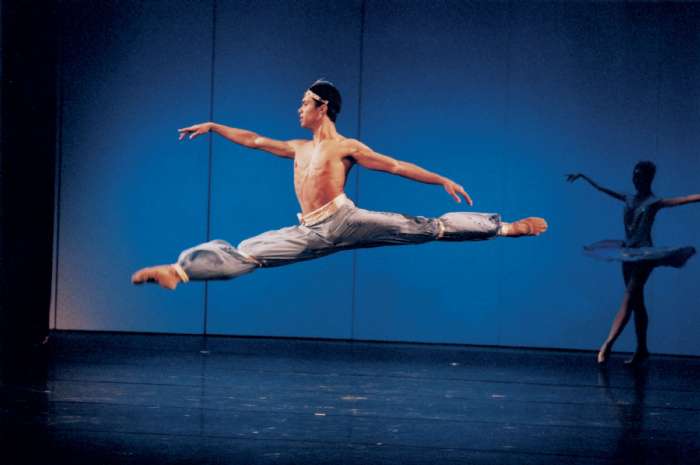

His performance was ardent. Passion for the sheer physical experience of the bravura choreography was fused with a vivid—indeed, blazing—idea of character and situation. It was evident immediately that this guy is a creature of the stage. His energy is extravagant. His technical ability in the big moves—-the huge, powerful leaps, the multiple turns coupling speed with control—is formidable. He grabs space the way a street gang carves out its territory, but he's never strained or sloppy about it. Launched into the air, his body remains perfectly composed, as if suspended in time as well as place, creating an indelible image. He retains the rawness and wildness of a kid left to grow up on his own. This is balanced, somewhat eerily, with mature self-possession and authority. You look at him and think: This is why I watch dancing. This is the real thing.

His performance was ardent. Passion for the sheer physical experience of the bravura choreography was fused with a vivid—indeed, blazing—idea of character and situation. It was evident immediately that this guy is a creature of the stage. His energy is extravagant. His technical ability in the big moves—-the huge, powerful leaps, the multiple turns coupling speed with control—is formidable. He grabs space the way a street gang carves out its territory, but he's never strained or sloppy about it. Launched into the air, his body remains perfectly composed, as if suspended in time as well as place, creating an indelible image. He retains the rawness and wildness of a kid left to grow up on his own. This is balanced, somewhat eerily, with mature self-possession and authority. You look at him and think: This is why I watch dancing. This is the real thing.

Second Sight: In Class

Intrigued, I ask to see him in class. Here's what I notice, besides what I'd already noticed:

He's got a lush plié, which gives him his extraordinary ballon. Not even the Danes in their heyday could produce a pas de chat as springy on ascent, as cushioned on its fall.

Turning: It's not the number of pirouettes from fourth position (six, actually) that's so remarkable. Everybody's on ball bearings these days. It's the ease with which he spools them out. It's the illusion of the body's rising vertically as it spins. It's the controlled finish, which is velvety—and confident to the point of appearing almost casual.

Self-possession: He has beautiful line, along with an ability to hold extended positions while exuding calm mastery. He has none of the late-adolescent gawkiness and uncertainty that cling to most of the other young men in the class. While the other fellows are still moving in awkwardly joined pieces, he uses his body harmoniously. He seems more grown-up, more self-contained, more whole than his peers—utterly at ease in his own skin.

Anatomy: Dancing can't help being about bodies, though the flaws legendary dancers have "overcome" are edifying legends in themselves. This dancer's feet are somewhat stiff, which is worrisome; he's unlikely to shine in petit allegro. His thighs are bulky—worrisome, perhaps, in one still so young, but remediable. He's not tall enough to partner the new breed of Amazon-scaled ballerinas; still, he's two inches taller than Baryshnikov and the more diminutive ballerina hasn't gone out of style. As for those muscular thighs, they simply weren't noticeable in performance. (It's imperative to remember when scrutinizing dancers in class that, in the end, performance is the only thing that counts.) He has a beautifully shaped head poised on a long, strong neck, and his hands are infallibly elegant. (Always notice a dancer's hands; they're as much a key to character as the face.) He's got a killer smile, which he bestows only, it seems, on people and occasions that have earned it.

Personality: There's something of the sulky antihero about him. At the barre, he doesn't exert himself unduly. You wouldn't single him out from his peers on the evidence of these bread-and-butter exercises—except, perhaps, for his instinctive musical phrasing of them. Later, when the instructor sets a traveling combination so thorny he apologizes for it in advance, Tidwell adds a gratuitous spate of pirouettes and a leg-switching split jeté—with a slightly disengaged-from-it-all air. What's this about? Boredom? Veiled defiance? His attitude is just the opposite in performance, where he's all eagerness. Apart from the intermittent displays of disaffection, his manner has an old-fashioned grace. A stage persona is already emerging: macho and at the same time very tender. In this he might be a cousin of ABT's Jose Manuel Carreño. Above all, he's noble. A danseur noble in the making.

Insight: The Interview Here's where you find out, perhaps, more than you want to know, more than you should know. Usually the best thing about an artist is his art. Yet we can't help being curious. Shortly after the Guggenheim sighting, I get to see Danny Tidwell close to, ask some generic questions, get some surprising answers.

Here's where you find out, perhaps, more than you want to know, more than you should know. Usually the best thing about an artist is his art. Yet we can't help being curious. Shortly after the Guggenheim sighting, I get to see Danny Tidwell close to, ask some generic questions, get some surprising answers.

He is eighteen years old. He grew up in a Virginia beach town. "I lived with my original family, my mom and two sisters, until I was about ten. My home life was not, let's say, an ideal situation." I'm as reluctant to ask for details about his precarious childhood as he is to offer them. "My dance teacher let me move in with her. I was always at her studio anyway, taking classes: jazz, tap, ballet. Denise Wall's Dance Energy. I call her my mom."

Competition and competitions were the spur. "I got outside my own little town and saw so many other kids from all over who were so good—a hundred times better than me—and so excited about what they were doing. That's where I saw what was happening and what was possible." He noticed that several of the most adept kids were pupils of the Kirov Academy in Washington, D.C. He decided that's where he needed to be. Doors open to evident talent; the Kirov Academy gave him a scholarship.

What brought about his conversion from jazz to ballet? "Jazz is raw, edgy, and real. It's a release. And when you get onstage and the audience receives what you're doing, it's so fantastic. Ballet is the opposite; everything you do is about rules. It's harder to get this dance form across to an audience, and there's always something you could do so much better. Those challenges keep me interested. Ballet is very idealized and very glamorous to me. You get onstage and you can just stand and move your arms and everyone knows how you want to be. I love the music. I love the movements. I love doing tricks. I love partnering with a girl—the feeling that you're together with another human being. I love connecting with the audience. I love it all, every part of it."

"I was at the Kirov Academy for two years. It was the best and the worst experience of my whole life." The unremitting rigor of the Russian training system, as he describes it, makes the place sound like a cross between boot camp and a monastery. The social isolation only intensified the pressure. The academy is a boarding school for an international crop of gifted students who have nothing in common but dancing and, it would seem, no space in which to do anything else. "I was totally shocked and totally stressed out. It worked for me, developing me as a dancer, but I saw it not working for others." After a summer of intensive preparation for the Shanghai International Ballet Competition, where he took the silver medal (no gold was awarded), he quit the Kirov program. "I couldn't live without my freedom."

"I went home, took a year off and did a lot of finding myself, went to New York and did jobs here and there—you know, Debbie Allen's shows, stuff like that. Then I got a scholarship to SAB [the School of American Ballet], which I hated even worse than I hated the Kirov Academy, the kids were so unaccepting, the teachers so unmovtivating. I needed to be pushed, I needed to know that ballet was more than just taking class, I needed for someone to care about me. I lasted there about two months."

The lure of competing saved a career that might have been over before it had even began. Tidwell decided to whip himself into shape "for Jackson" [the USA International Ballet Competition in Jackson, Mississippi—these things have fancy names] and copped the silver. Kevin McKenzie, ABT’s artistic director, saw a video of his prize-winning performance and suggested to John Meehan that he offer Tidwell a place in the Studio Company. No audition was required.

Now, toward the end of a year with this springboard group, Tidwell is sure he has found his place. His immediate goal is a slot in the parent company, though he still keeps up his jazz and acting lessons "so that Broadway will be an option if ballet doesn't pan out." Joining the ABT corps, it turns out, is only the first in a series of escalating aims. Call them dreams, if you prefer, but, while Tidwell’s manner is disarmingly modest in talking about them, his focus is precise. When it comes to roles, he hankers after the hero parts, which obviously means attaining high rank on the roster. "I want to do my Swan Lake, my Giselle, my Don Q, my Bayadère. I want to conquer those roles. I'd also like to do Romeo and Juliet. Of course I'd like to learn how to dance Balanchine the right way, but my training has been for those 'big' parts. I also love contemporary stuff. I feel sometimes that I'm better at it than I am at ballet," he adds wistfully.

Stalwartly, he continues, as if, once having confessed to ambition, he can reveal the full extent of his hopes. "I want to choreograph, too. I've made some dances already. Naturally I want to be a principal dancer. Then, when I'm finished dancing"—deep breath before he dares to bring it out—"I'd like to be the artistic director of ABT." He has the grace to pause after this, note my astonished silence, and add, "Well, if not here, then maybe somewhere else."

Meanwhile, he's still young enough in his career to be looking for role models. His choices, keen-eyed and intuitive, suit the kind of dancer he promises to become. "First, Jose Manuel Carreño. He's beautiful. It's the way his muscles work and the way he makes everything look effortless. His dancing is so clean and clear, and yet it's not finished, ever. When he's offstage, you want him to come back, because you don't want him to finish. And he never does; he never stops. When he performs, he's not showing off his talent; no, it's a conversation with the audience. He seems to be saying, 'I'm dancing for you.' This is so comforting and inspiring.

"Then Carlos Acosta. He's a freak of nature. He's so tall and his movement is so huge. He's such a story. When he runs—well, he's just this big, massive man just running and turning and jumping. He defies gravity and he turns more than you'd ever think possible—and he still holds his fifth position perfect. Amazing.

"And Desmond Richardson, especially in his contemporary dancing, which is absolutely brilliant. You should see him in hip-hop class—moving and isolating and just living."

"But the one is Jose Manuel."

Fast Forward

Shortly after our interview last spring, Tidwell’s career took off. The Studio Company toured to Belfast and London, where, according to eyewitness reports and newspaper reviews, the young dancer was a sensation. Back in New York, following performances at the Kaye Playhouse, he was summoned by the parent company to join its ranks, without having to do the customary apprentice stint. Like every newcomer, he learned a slew of corps de ballet roles and, with just a single rehearsal, carried out a soloist assignment—the bravura Neapolitan Dance in Kevin McKenzie's Swan Lake. "He did tremendously well," John Meehan reports, adding dryly, "He has not gone unnoticed by the powers that be." At the same time, Meehan counsels patience. "In a large classical ballet company, you have to learn to wait." And Tidwell himself has grown more temperate—cautious, perhaps—in expressing his hopes for the future. He's still going for the gold but reports, "This is my year for observing." Meanwhile, New York balletomanes will be observing him, in the course of ABT’s upcoming engagement at the City Center, October 22-November 9, which will feature two of his role models, Acosta and Carreño. Every move these heroes make will serve the young dancer as a lesson.

Coda

Will Danny Tidwell be “the one” of his generation? There’s no telling, really. To become and remain a memorable dancer takes staying power, the kind of talent that continues to expand as it rises to ever-increasing challenge, an imagination that refuses to be extinguished by the relentless pressure of the banal—and lavish good luck. Whoever the great ones in the rising generation turn out to be, though, right now they probably look a lot like Danny Tidwell.

Photo credits:

1. Rosalie O'Connor: Danny Tidwell in Le Corsaire

2. Marty Sohl: Portrait of Danny Tidwell

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

Merce Cunningham Dance Company / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, New York City / October 14-18, 2003

Dancing usually hangs out with music—and with good reason. Think rhythmic, structural, and atmospheric support. Think Tchaikovsky-Petipa; think Stravinsky-Balanchine. Merce Cunningham, celebrating the 50th anniversary of his company at BAM this week, was a pioneer in disconnecting the two arts, inviting them to exist in the same place and time yet avoid co-dependency.

With avant-garde practitioners like John Cage, Cunningham evolved the policy of commissioning composers to provide a score of a specific duration (giving them no other parameters or clues to his own intentions), while he created choreography of the same length. Music and dance met only on opening night of the production. So it was not entirely astonishing to learn that a pair of forward-leaning rock bands, Radiohead and the Icelandic Sigur Rós, would provide the sound for Cunningham’s newest work, Split Sides, the ostensible climax of an event-filled anniversary year, though the choreographer usually goes for more highbrow types. But rock commands an audience and BAM, like any other producing organization, needs to sell tickets.

It should be mentioned here that the use, in productions featuring contemporary choreography, of musical and visual artists who will attract their own crowd to the performance is nothing new at BAM. Indeed, this shrewd blend of avant-garde elements, historically related to holes in the wall, with astonish-me spectacle has been a regular practice of the house’s Next Wave series since its inception in 1983. Some of the combinations have been truly organic, the happiest, perhaps, being the teaming of Philip Glass, Robert Wilson, and Lucinda Childs for Einstein on the Beach. Others have been contrivances with an opportunistic air. Fortunately, in Cunningham’s case, given the persistent integrity of his work and his personal dignity (a mix of modesty, piercing intelligence, and wit), nothing the man is involved in looks cheap or merely canny.

Nevertheless, in addition to the musical choice made regarding Split Sides, other aspects of the dance’s construction turned venerable Cunningham practices into publicity stunts. Most important was the roll of the dice, an I Ching practice that allows chance, through its random effect, to enlarge one’s sphere of action beyond the narrow, prejudicial dictates of personal choice. For the 40-minute Split Sides, Cunningham created a pair of 20-minute dances and ordered up two backdrops, one each from Robert Heishman and Catherine Yass, and two sets of costumes and lighting plots, from company regulars James Hall and James F. Ingalls, respectively. A roll of the dice before each performance would dictate the order in which the elements were used in the two-part piece. If all the journalism this adventure generated could be turned into a $100 grant per word, Cunningham might never have to go begging again.

For the opening night gala, attended by a packed house of the rich, the famous, and the curious, augmented by squads of rock music fans and their Cunningham-reverent equivalent, as well as an extra component of security folks, the dice rolling was done onstage, in the presence of the musicians who would later be hidden in the pit and a few dancers picturesquely warming up. It featured New York’s Mayor Bloomberg at his most aggressively exuberant (to compensate for Cunningham’s decades of under appreciation?), with the rolling done by celebs like former Cunningham collaborators Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Cunningham ur-dancer Carolyn Brown.

Eventually, after all the brouhaha, here it was, another Merce Cunningham dance, and this time, as chance would have it, not a particularly distinguished one. Following the dictates of the dice, the first segment used Part A of the choreography, Radiohead’s accompaniment, Heishman’s backdrop (like Yass’s, a pale blow-up of an abstract photo), and Hall’s black and white costumes (hyperactively scribbled-over unitards) as opposed to the ones aggravated with psychedelic tints; the second segment, the alternatives.

Neither sound score was what devotees of, say, Bach—favored by choreographers of various persuasions—would call music. Yet neither, though far less intellectually sophisticated than the work of, say, John Cage, was radically different, in effect, from the aural accompaniment Cunningham has traditionally provided for his dances. Hazard determined whether or not, at any given point in the proceedings, it meshed with the movement or served as a maddening distraction. Both Radiohead and Sigur Rós laid down a background of hypnotic New Age chimes-and-gongs (music to space out on), agitating it with the static of indecipherable speech, mechanical noise, and threats from nature (thunder, the buzz of swarming insects). Presumably the competing, fragmented sounds and rhythms reflected the contemporary mindset. To my ears—untutored in such matters, I grant you—all of it sounded terribly dated. Ignoring its hovering partner, the movement went serenely about its business.

Unfortunately, that business seemed to be a simplistic version of what Cunningham usually does—as if, having lured in a crowd unfamiliar with the sort of dancing he’s evolved in the last half century, he'd made his work more readily accessible. This friendly but artistically diminishing impulse was most evident in the structure department. Cunningham habitually composes long, flowing ensemble passages, streams of dance that seem capable of going on forever. Within these, an individual viewer is free to highlight, through his attention, the action of smaller groups. As if the choreographer had been reluctant to tax the patience of neophyte watchers, Split Sides makes a clear distinction between brief stretches of group movement decidedly reduced in complexity and solos, duos, trios, and so on that stand out—sharp and self-contained—like vaudeville turns. (The opening night crowd applauded several of them with relish.) What’s more, although Cunningham rarely dictates tone, there seemed to be several deliberately humorous patches—playful, even arch arrangements for twos and threes in which the dancers flirted and clowned like figures from some postmodern commedia dell’arte. I felt as if I were watching Cunningham 101, though that imaginary course would, more appropriately, consist of 20 minutes chosen at random from any of the choreographer’s masterworks and viewed in a state of calm receptivity.

For me, the treat of the evening was the 2002 Fluid Canvas, being given its New York premiere. In it, Cunningham's 15 dancers, ravishingly lighted by James F. Ingalls, epitomize their breed. They’re a highly refined race noted for fluidity, fleetness, psychic as well as physical harmony in the most off-kilter positions, high alertness, and deep concentration. Several of the beautiful glimmering unitards—in gunmetal and aubergine—that James Hall designed for the piece are cut deep to the waist in back, and it was a surprise to see, not five minutes into the action, the gorgeously muscled flesh glistening with sweat, because the figures seemed superhuman creatures for whom effort was unnecessary.

The choreography makes much of unusual postures, sometimes with so much torque to them and such anti-intuitive arrangements of the arms, the dancers look like gargoyles—albeit extraordinarily handsome ones. At the same time, Cunningham allows the upper body to contradict its lower half, so that two very different kinds of activity are going on at once. These explorations do not so much refute classical ballet (which plays a much larger role in Cunningham’s resources than, say, the modern-dance inventions of Martha Graham, with whom once he danced) as they investigate, with a sympathetic curiosity, the reverse of its coin.

More typically of Cunningham—though more emphatically than usual—Fluid Canvas calls our attention to the varying numbers of dancers on stage at a given time. It also makes us acutely conscious of negative space. The voids created on the stage are as potent as the areas filled with human bodies carrying out a wide and subtle range of ever-shifting designs. Towards the end of the piece, the dancers sit hunkered over their own bodies, heavy and one with the earth, it would appear. Suddenly, they help each other up and rush swiftly, light as windswept autumn leaves, into the wings. Once they’ve vanished, the stage remains empty for a few seconds, just long enough to let the emptiness register, then the light is extinguished and the curtain falls. The dance isn’t over, Cunningham instructs us, until our eyes and minds take in the significant condition of not-dancing.

Photo credit: Jack Vartoogian: Daniel Squire and Holly Farmer in Merce Cunningham's Split Sides

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

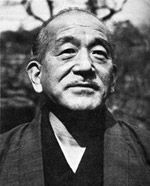

"Yasujiro Ozu: A Centennial Celebration" / Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater, NYC / October 4 - November 5, 2003

Dance aficionados as well as film connoisseurs will be drawn to the Walter Reade Theater for the Film Society of Lincoln Center's "Yasujiro Ozu: A Centennial Celebration," October 4 - November 5. The lure for the dance crowd? The iconic director's insight into movement and his rendition - always sensitive and frequently sublime - of feelings that lie past the reach of words.

Those just glancingly acquainted with the work of Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963), as well as his committed fans, characterize the Japanese film director as the master of non-action. At heart, his films concern themselves with being, not doing - an attribute of the Zen thinking with which his outlook is allied. Ozu embodied the quality of transcendent stillness most perfectly in his middle period - extending from the mid-thirties to the mid-fifties - once he had, somewhat reluctantly, adopted sound, but before he had, with equal reluctance, succumbed to color. (His earliest films, enchanting silents, are often highly animated.)

Those just glancingly acquainted with the work of Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963), as well as his committed fans, characterize the Japanese film director as the master of non-action. At heart, his films concern themselves with being, not doing - an attribute of the Zen thinking with which his outlook is allied. Ozu embodied the quality of transcendent stillness most perfectly in his middle period - extending from the mid-thirties to the mid-fifties - once he had, somewhat reluctantly, adopted sound, but before he had, with equal reluctance, succumbed to color. (His earliest films, enchanting silents, are often highly animated.)

Creating a peerless series of black and white "talkies" over two decades, Ozu probed the extraordinary ways in which limitation can serve to reveal the intangible (and most significant) aspects of existence, focusing the attention on essences rather than events. One of his most apparent means was stasis: minimal body and facial movement for the actors (emoting was thus precluded) and a fixed position for the camera, which then regarded the material before it like the unwavering eye of God. What is most curious about this denial of motion is the tremendous importance motion assumes when it does occur. Like that of very different masters - Balanchine, Ashton, and Tudor - Ozu's "choreography" creates epiphanies by manifesting intense, unarticulated feeling through physical action. And it does so in remarkably varied ways.

In the 1953 Tokyo Story, as is typical of the mature Ozu, plot has become as fragile and translucent as a silver-penny petal. The film is dominated by a theme that obsessed Ozu throughout his career: the nature of human experience as it is expressed in the relationships between parents and their grown children.

An aging pair make a momentous visit to the big city where they find their adult offspring largely too preoccupied with their own concerns to give them the loving respect and attention one might assume to be a parent's due. Resigned to their disappointment, they journey home, whereupon the mother succumbs to a stroke and lies unconscious on her deathbed. Ironically too late, the children gather in attendance around her pallet. Although charged with feeling, the scene - with the inert body at its center - is utterly quiet and self-contained. It's almost a still life, the actors and the camera are physically so subdued.

The younger brother arrives after the others, explaining he'd been away on business when the summons came. He's literally too late; while the camera gazed outward to the town, the sky, the river - the larger, sentient universe - the mother expired. By custom, her face is covered with a square of white cloth. "Look at her," an elder sibling urges the latecomer, "she looks so peaceful." The son moves to lift the cloth and, with typical Ozuian obliqueness, the camera - its rhythm as unforced and acutely timed as a sleeping child's breath - cuts away. So we don't see what the son sees - the mother's placid face in death. We don't need to. It already exists in our imagination. Nor do we see the son's face; Ozu would consider even such a minor bit of melodrama tactless both emotionally and aesthetically. Instead, he slews the camera around to the other figures' response, a kind of visual harmony to the unrecorded event. Kneeling, passive as hills, gazing down at their hands, they lift their heads to witness their brother's sight, then, as one, incline slightly from the waist and neck, instinctively bowing to the sacredness of the moment.

This passage from Tokyo Story epitomizes the beauty and deftness with which Ozu makes his primary emotional point through a single move - the bow - in an environment of physical and emotional quiescence. In The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice (1952), the climactic scene is based upon a journey - geographically minute and on domestic turf, poetically immense and structured as formally as a classical ballet. An estranged husband and wife, having reached the point of reconciliation, penetrate by stages into the core of their home, the kitchen. A modest room at the back of the dwelling, down several stairs, it fulfills a basic human need - hunger - yet this long-wed couple hardly knows where it is. (The erotic parallel is obvious, though it's not in Ozu's nature to belabor it.)

The husband is a simple man - blunt, good-hearted, tenaciously unaffected. His taste is for the common, unpretentious things of his background. They fit him, he explains at one point, later amplifying his observation: "It's how a married life should be." Superficially sophisticated, disappointed in the dullness of their union, his wife has rebuffed him for his lack of refinement. Now, having learned through pain to understand and appreciate each other, they celebrate by going in search of a midnight bowl of rice doused in green tea - a peasant meal, typically consumed with slurping relish.

The kitchen is hidden, almost unknown, territory to this comfortably-off pair, but to preserve the intimacy of their newfound accord, they choose not to summon their sleeping maid to serve them. Side by side, touching each other so lightly and unemphatically, their physical contact is barely visible, they slide back the wall panel of their living room, pass through a narrow, dimly lit corridor, slide open yet another panel, and illuminate a primitive hanging lamp that discloses the humble kitchen so mysterious to them. Together, they prepare their repast - he gently draws back her kimono sleeve as she washes her hands - and return by the same route, soft-edged shadows on the translucent panels they shut behind them.

Their journey - with its unstressed sexual parallel - is one of venturing by degrees, of lifting veils and entering uncharted passageways. As it progresses, the bourgeois environment and the bourgeois situation dissolve into evocations of legendary quests: Orpheus descending into the underworld in search of Eurydice, the prince of Perrault's Sleeping Beauty crossing the barriers that separate him from his heart's desire.

Late Spring, made in 1949 and perhaps Ozu's most exquisite achievement, uses an image of nature in motion to express human feeling. The tale - again, one that Ozu reiterated as if he could never be done with the issue - concerns a widower who realizes he must release his beloved and devoted daughter from tending him into a life of her own. She's reluctant to leave the serene, secure shelter of her girlhood, so he deceives her into thinking she must marry because he wants to remarry. The idea of her father's entering into a sexual alliance after her mother's death revolts the young woman. Matters come to a crisis at a Noh performance, when the daughter sees her father exchange gazes with the lovely widow who will presumably appropriate her place.

This being an Ozu film, not a word is spoken directly about the matter, but the daughter's swiftly mounting feelings of anger and desolation are clear, almost unbearable in their repressed intensity. The theater scene ends and, as is Ozu's custom in shifting locale, a landscape shot is inserted. Technically, it's a transitional device; aesthetically, it's a container for human emotion so dense and many-faceted it can't be particularized. Several such shots, earlier in this film, showed a few thin, barren tree trunks. Now Ozu's camera looks up at a flourishing tree, proudly set against the blank sky. At the peak of its maturity, the tree is wide and thickly branched, in full leaf. A wind blows through it, making its foliage dance in the sunlight, as if to emphasize its vitality, and its already luxuriant expanse seems to inflate, like a lung. The tree - whether you take it to be just a tree or a symbol of unquenchable, continuing life - is breathing. The breath is the breath of immanence.

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

This week's performances of Ballett Frankfurt at the Brooklyn Academy of Music mark a critical stage in the career of William Forsythe, who has shaped the company according to his singular aesthetic. I've invited the dance writer Roslyn Sulcas, our New York expert on Forsythe, to provide some background. Here is her report:

William Forsythe has been quietly enlarging the world of classical dance over the last two decades. Born in New York, and trained at the Joffrey Ballet School, Forsythe moved to Germany in his early twenties to join the Stuttgart Ballet and has lived there ever since. Although he has been a major presence on the European dance scene since Rudolf Nureyev commissioned In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated for the Paris Opera Ballet in 1987, it is only during the last few years that he has become better known to an American dance public, as companies nationwide have acquired works like In the Middle, Herman Schmermann, and The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude.

More frequent tours to New York in recent years have also meant that Forsythe has been able to show in greater depth the elaborate movement vocabulary that he and his dancers have developed during his tenure in Frankfurt, alongside the inventive theatricality and creative use of lighting that characterize his work. Even if it often strays from ballet’s emphasis on lengthened line and effortless virtuosity, much of Forsythe’s work is engendered by the ideas present in the forms of classical dance. It also looks balletic because he uses classically trained dancers, whose bodies instinctively enact the formal rules (turn-out of the hips, pointed feet, the extension of the spine and limbs, epaulement) that characterize the art form, even as they deploy it in unconventional ways.

The result is dance that (among other things) disregards the vertical planes to which the classical positions of the body are fixed, uses the thrust and momentum of the dancer’s weight to alter conventional transitions between steps, deploys the upper body to generate movement rather than accessorizing the legs, and offers a complex display of coordination and counterpoint.

Sadly, the ensemble with which Forsythe has developed this distinctive vocabulary and a huge repertoire of dances will cease to exist as of June next year. The reasons for the company’s dissolution remain somewhat murky. In early summer last year, rumors circulated that a newly politically conservative Frankfurt city council, which funds the company as part of the Frankfurt Opera ensemble, was reluctant to extend Forsythe’s current contract past its expiration date of June 2004, preferring to re-establish a more conventional ballet company in the city and hoping to cut costs on an increasingly beleaguered cultural budget. (An illogical idea, if true, given the even greater expense of running a conventional ballet company.) After the media seized upon the news, thousands of e-mails and faxes from all over the world, protesting this decision, poured into the mayor’s office, prompting a statement that there was no intention to fire Forsythe. By then, however, Forsythe had decided that he didn’t want to go on in an atmosphere that was hostile to his work. (Subsequently, the city council announced that Ballett Frankfurt could continue if the budget was cut by 80%.)

The dissolution of Ballett Frankfurt is of great consequence to the dance world. Over two decades, Forsythe transformed this company into one of the most consequential contemporary ballet ensembles in the world, creating dances out of a profound body of deeply ingrained physical knowledge. Choreographers need their tools - dancers - and the best tools are those who have been honed into perfect form for the work at hand. Forsythe will, of course, continue to be sought after as a dance maker, and will no doubt go on to make important pieces; there is talk at present of his forming a smaller company that would be partially funded by the states of Saxony and Hesse. Nonetheless, those twenty years’ worth of ballets, the heritage present in the collective body of dancers, is a significant loss to the world of dance, and well beyond.

© 2003 Roslyn Sulcas

Ballett Frankfurt / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, NYC / September 30 - October 5, 2003

I wish I liked William Forsythe's work more. After Ballett Frankfurt's opening night at BAM, I felt an inch closer to appreciating it - as the enthusiastic audience, peppered with dance-world celebrities, clearly did. But no more than an inch. Yes, the vocabulary is inventive (if narrow). The pictorial sense at work is superb. The Forsythe-groomed dancers perform with extravagant energy and commitment. But the dances seem to be telling the same story over and over again - or no story at all. You watch these creations and nothing happens to you. (For "you," read "I" and "me.") This choreography doesn't galvanize my feelings; it leaves my perception of the universe intact. I walk out of the theater exactly the same person I was when I walked in. "I just don't get it," complained one of my colleagues in the second intermission, waving his hand toward the stage as if to indicate the whole Forsythe oeuvre. But he and I are in the minority.

Forsythe calibrated his program - perhaps Ballett Frankfurt's farewell to New York - astutely. Two largish group pieces framed a pair of chamber-scaled works, a women's duet and a male quartet, the public encasing the intimate. Austere elegance governed the overall effect. Minimal music, provided by Forsythe's regular sound man, Thom Willems, or silence broken only by the dancers' emphatic breathing accompanied lush, high-voltage dancing. The "scenery" consisted merely of black drops, in heavy velvet or translucent gauze. The costuming alternately reflected dancers' practice clothes and pajama-casual schmattes - the antithesis of fancy dress that's almost a moral stance these days. Talk about suave!

The Room As It Was served well as a curtain raiser since it presents Forsythe at his most typical. Eight dancers come and go, working in ever-shifting small groups or as loners tangentially connected to the "crowd." Hyperactivity - strikingly, in the torso and pelvis as well as the arms and legs - contrasts with slow swirls that twist off the vertical to spill, still writhing, into horizontal positions on the floor. Small vortexes of motion occur constantly. Sometimes they're charged with a little feeling, even a little drama; more often they look like calculated investigations into the possibilities of the human anatomy.

Images fleetingly suggesting confrontation and combat interlace with tentative, solicitous handholds, as if the participants had joined an encounter group and were sensitively trying to figure out how to get along with one another. Shards of disaffection and absurdity à la Pina Bausch surface too, as in a sequence where a fellow repeatedly attempts to plant a gentle kiss on the neck of an indifferent young woman who doesn't even bother to repulse him but merely deflects his efforts as she waits impatiently for a better offer.

Though the piece is very bright and busy, it doesn't make a dent in your consciousness until its very last moments, when a mid-stage scrim rises, doubling the depth of the available space and revealing a pair of dancers in shadow. A fragment of music is heard; it seems to announce that the show has now begun.

(N.N.N.N) - Forsythe goes in for abstruse titles - uses lots of gestures that lie (in the middle, somewhat elevated, you might say) between pantomime and dancing. When the full cast of the piece - four guys - is involved, clustered tight, with no music to help out, timing becomes a tour de force. The imagery borrows from sports, martial arts, artificial respiration, and just plain goofing around. Fighting and bonding, Forsythe seems to be saying, that's what men do, and the clue to their nature is that they do it simultaneously. Unfortunately, on this occasion, they do it for far too long. The extended proceedings begin to look aimless because, unlike Merce Cunningham - the master of going on at length without many clues to mark where we are, where we're heading, and what's happening en route - Forsythe can't make us confident that his choreography harbors an internal structure, albeit a hidden one.

In Duo, Forsythe shows us what women do - understand the aspects of life that can't be seen or explained and, via this intuition, become one with the inner workings of the world. Although it has its share of Forsythian middle-of-the-body wriggles and slews off the vertical, the movement language of this duet emphasizes long stretched limbs, diagonalled arms suggesting the hands of a clock, the swing of a pendulum. Moments of stasis, alternating with calmly paced action, lend the bodies a sculptural effect and, with that, an emotional dimension. The women seem to be allying themselves with passing time, mastering it by giving in to it.

Women can also, Forsythe observes as a footnote, dress to kill. And he has dressed this voluptuously bare-legged pair in shiny black bikini briefs, veiling their torsos and arms with the sheerest imaginable jet stretch fabric, so that the top of the body appears naked but glamorously shadowed. Having noted what a sheath of see-through black stocking can do for the leg, he made the imaginative leap to what it might do for breasts.

One Flat Thing, reproduced, used as the program's closer, is unabashedly based on a gimmick: It opens with fourteen dancers aggressively rushing forward, pushing before them large utilitarian tables that, arranged in an uncompromising grid, nearly fill the stage. They proceed to dance on top of them, underneath them, and in the stingy spaces left between them. The effect is that of humanity alive and kicking despite a world that has almost no space - space being to dancers as essential as air. Inevitably, the whole business is ridden with clichés: The tables become autopsy slabs, coffins, and the like; dancers not engaged at a given moment stand at the back of the space in a twilight of inaction, staring, expressionless, at the audience.

The piece is almost unwatchable, partly because, as with (N.N.N.N), its structure is ill-defined. Between the initial attack of the tables and their withdrawal, which closes the dance, the activity seems to occur almost at random, utterly even toned, threatening to go on forever, giving the viewer far too much time in which to ask, "What's this about?" Are we watching teenagers rampaging in their high school cafeteria or yet another one of those apocalyptic affairs art is prone to? Both maybe, and in both the spirit of Jerome Robbins seems not very far away.

Thinking about these works in retrospect as I was writing about them, I found more in them to admire than I did when I was watching them. Is this because a central aspect of Forsythe's choreography is conceptual rather than visceral? I must say I've always been leery of choreography that appeals more as idea than as dance.

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Rebuilding Gulf Culture after Katrina

Douglas McLennan's blog

Art from the American Outback

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

music

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

visual

Public Art, Public Space

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog