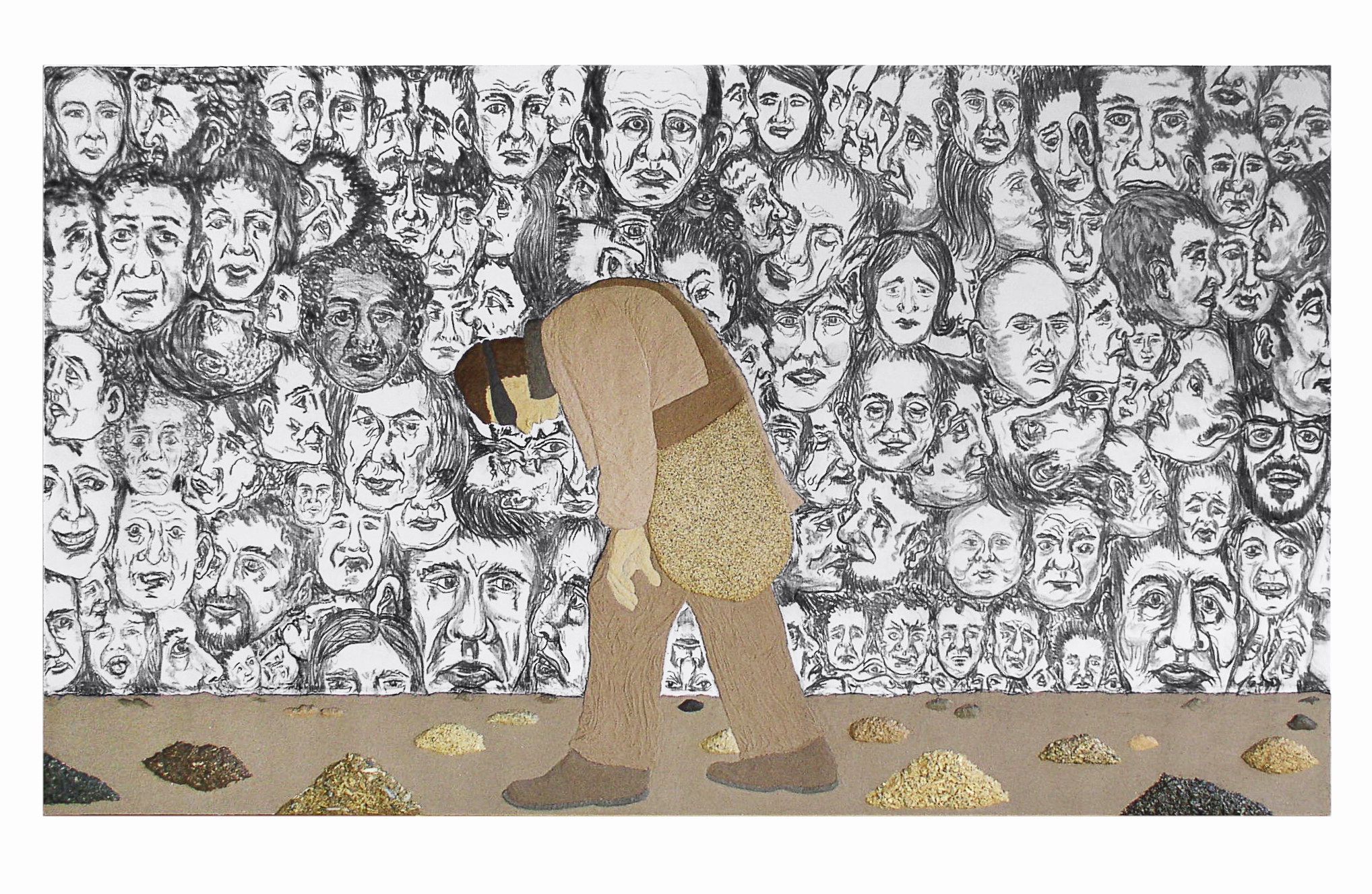

Houston artist Wayne Gilbert makes paintings out of cremated human remains.

Most people who have observed his work wonder first where he obtained the material, which he mixes into nearly-colorless resin before applying with a  palette knife to stretched canvas. The recent summer day we spoke in his vast home and studio, Gilbert told me that he had just come from the grocery store, and in the parking lot an acquaintance had offered his mother’s ashes for a future painting. Those in his circle have been generous at times. One of Gilbert’s early paintings is titled 8 of My Friends, triangular canvas with increasingly longer even-width strips of carefully organized ashes.

For the most part, however, Gilbert says the cremated human remains he uses have been left behind at funeral homes, where they stay for a required period before funeral directors are at their own discretion as to what should be done with them. The notion that many of the “persons†appearing in these paintings were abandoned shortly after death only adds to the haunting metaphors in the finished pieces.

The ashes are hardly mono-chromatic. Some of them are a soothing beige, others appear in gradations of yellow ochre. Some are even, as Dylan Thomas would say, “starless and Bible black,†suggesting a range of techniques or perhaps insistencies used when incinerating a corpse.

For me this work provokes strong emotions and troublesome personal pre-occupations, though I am nonetheless completely taken with it. When my brother died suddenly at age 45 and was later cremated, for several months his ashes stayed quietly in an industrial thick tubular metal urn on my mother’s living-room oak sideboard. The contrast between those two materials was ironic yet comforting, in sharp contrast to my brother’s turbulent life.  And strangely, the urn reminded me of those hard-working spinning pneumatic tubes at my local drive-in bank. Several months later, we buried my brother’s cremains in a cemetery plot. It is impossible for me to think of them as pigment for a painting, as deeply impressed as I am with the care and respect Gilbert has towards his “subjects,†for lack of a better word. Upon deeper inspection, it appears that the themes are far beyond the lives of the particular deceased.

It is a mistake to think of these paintings as mere elegies. In 2004, People Magazine ran a feature on Gilbert. Following that story he received calls from around the world from people who wanted him to make a memorial painting from a relative’s remains. Gilbert stood to profit. Many of the callers told him, “Money is no object.†But he turned every one of them down, saying plainly that he doesn’t make “mortuary art.†Rather, he told inquirers that their loved ones could become part of what he calls his “universal family.†The back of each and every canvas Gilbert has created shows the names of the deceased and the location of their remains. He never blends their ashes on a canvas, though he said that one day he might explore the idea of marriage with the combined cremains of a couple. So far, he has not diverged from his original strategy.

If it is not mortuary art, then what exactly is it? Gilbert says that his work with human cremains provokes a new way of thinking about the “priceless†dimension of art. He knows it is off-putting, yet he persists. “As long as I’ve been painting,†he said with irony, “I’ve never had a museum invite me to display one of these, and I’ve never been invited to be in a show.†Every exhibition has been initiated through his own means. When the paintings have been displayed with the work of other artists, Gilbert says that people browse the gallery looking with equal attention, until they learn about his materials. “There’s something that takes them back for a second look,” he explained. “Whatever that is, that’s what the paintings are about.”

6 responses to “What Remains on the Canvas”

It must be very difficult to find people willing to model for this Artist.

I am disgusted by the thought and apparently the fact that human remains have been used by any person who considers himself an artist as an art making material. Although there is historic evidence that mummy was used as a pigment in the 18th c., that is ground up Egyptian mummies, it was never a major art material. The point of my comment is that human remains should be respected as they have been by most civilizations. Since many earth pigments look like the products of cremation pwhen laced in the appropriate context in a work of art, why then use actual remains?

You’ve got a lot to learn about respect, Mr. Brown.

All human beings have a lot to learn about respect, even you. The word respect has evolved from it’s original meaning in 1300 when it meant looking back in time to something of importance or significance to one or many human beings. There has been significant research done on this subject primarily by archeologists, sociologists, historians, art conservators, museum specialists, etc. in at least the past 50 years.

Every day of my life, even when I’ve been ill or indisposed, has been a learning experience. I have no respect whatsoever for anyone who defiles human remains and that includes whatever form the flesh and bones of former living human beings are found. I know of no human culture that has not developed rituals for attempting to keep the memory of those who are no longer living to be kept alive in the minds of the living. Even elephants grieve over the remains of the remains of other elephants whom they find along their trails in search of food, water and safety. Their grieving over the remains of their own family members has been described by some experts on elephants as more complex than the funeral rites advanced civilizations give at the deaths of their most esteemed of their societies. By the way, do you remember the televised funeral of Princess Di (08-31-97)? What do you think of the millions who grieved over Princess Di’s tragic death would think about the idea of having her remains used as a raw material for the manufacture of an art object to be displayed and sold?

And you, sir, have a lot to learn not only about human remains but about visual art.

Dear Hilton,

thanks for reading and your comments. That’ s an intriguing shift in the latter part to the televised funeral of Princess Di. I have enormous respect for Wayne Gilbert and I’m sure he’ll be intrigued with your take on his work. If you could meet him in person, he would really enjoy discussing this with you, so please do let me know if you make it to Houston in the future!

“Gilbert told me that he had just come from the grocery store, and in the parking lot an acquaintance had offered his mother’s ashes for a future painting.”

“For the most part, however, Gilbert says the cremated human remains he uses have been left behind at funeral homes, where they stay for a required period before funeral directors are at their own discretion as to what should be done with them. The notion that many of the “persons†appearing in these paintings were abandoned shortly after death only adds to the haunting metaphors in the finished pieces.”

i think it’s clear that Hilton Brown needs to understand, accept, and RESPECT that what is right and true for Hilton Brown is not necessarily right nor true for any other person on the planet. its views are clearly NOT shared by either the people who give freely of their deceased relatives ashes for use in Gilbert’s paintings, nor by those who leave those ashes unclaimed at funeral homes throughout the country. (and if our bodies were so sacred, would we, each and every one of us, just leave our own bodies where they fall when we’re done with them? i think not. yet that’s exactly what each and every one of us does, without fail.) it is for every person to decide what is sacred to them and what is not, and many people love the idea of something artistic and creative being done with their mortal remains after they’ve finished with them. it’s a lot more interesting and useful (and, one might add, “respectful”) than simply dumping the ashes into the water or scattering them over the ground the same as we do our garbage.