Terri Lyne Carrington (drummer, Inst. of Jazz & Gender Justice), Orbert Davis (trumpeter, “Immigrant Stories“) and Marc Ribot (guitarist, Music Workers Alliance) talked with me on The Buzz, podcast of the Jazz Journalists Association about their engagement with social issues. Long transcript posted for those who read faster than they listen. But what happened in […]

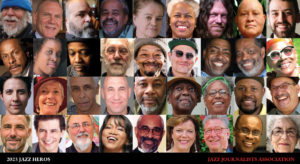

Across North America, 29 “Jazz Heroes”

Twenty-five years ago the Jazz Journalists Association began to identify and celebrate activists, advocates, altruists, aiders and abettors of jazz as members of an “A Team,” soon renamed “Jazz Heroes.” Today the JJA announced its 2025 slate of these Heroes, 29 people across North America who put extraordinary efforts into sustaining and expanding jazz in […]

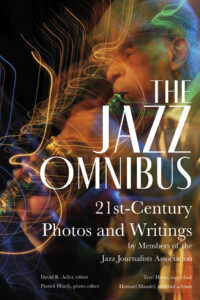

Introducing The Jazz Omnibus

I’m proud of my two published books (Miles Ornette Cecil – Jazz Beyond Jazz and Future Jazz) and my unpublished ones, too; the two iterations of the encyclopedia of jazz and blues; I edited, and my collaborations with some musicians creating their own books — but right now I’m crazy enthusiastic about The Jazz Omnibus: […]

It’s Jazz Appreciation Month: Hail Jazz Heroes!

Since 2001, the Jazz Journalists Association (over which I preside) has celebrated some 350 “activists, advocates, altruists, aiders and abettors of jazz,” as Jazz Heroes. The class of 2024 Jazz Heroes has just been announced, recognizing the good works of 33 people whose efforts extend from the Baja-San Diego borderland to Ottawa, Canada, through 27 […]

36 Jazz Heroes in 32 US cities – and there are many more

The Jazz Journalists Association announces the 2023 Jazz Heroes — “activists, advocates, altruists, aiders and abettors of jazz,” formerly the A Team — emphasizing as it has annually since 2001 that jazz is culture that comes from the ground up, by individuals crossing all demographic categories, working frequently with others and beyond basic job definitions […]

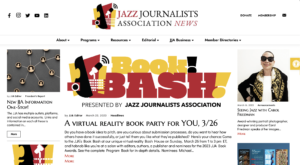

Jazz journalism online, virtual reality book party

I’m inordinately proud of the new JJANews website because it makes easily accessible the videos, podcasts, articles with photos and online-realtime activities of the Jazz Journalists Association, such as lthe March 26 public Book Bash! with authors, editors and publishers, being held on on our unique virtual reality SyncSpace.live site — plus background/office assets, in […]

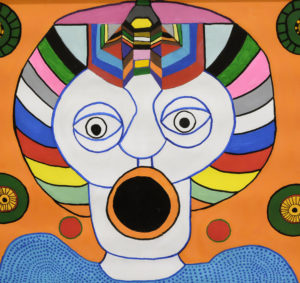

“Supermusician” Roscoe Mitchell’s paintings revealed!

Roscoe Mitchell — internationally renown composer, improviser, ensemble leader, winds and reeds virtuoso who has pioneered the use of “little instruments” and dramatic shifts of sonic scale in the course of becoming a “supermusician . . .someone who moves freely in music, but, of course, with a well established background behind . . .”* reveals […]

Armstrong in Chicago 100 years ago sparked jazz

Lest we forget: In 1922 Louis Armstrong arrived in Chicago from New Orleans, with his wife Lil Hardin, mentor King Joe Oliver and colleagues such as the Brothers Dodd (clarinetist Jimmy, drummer Baby) kick-starting jazz into the most spontaneous, joyful, virtuosic, collaborative art form the U.S. has yet produced. The Jazz Institute of Chicago celebrated […]

Electroacoustic improv, coming or going? (Herb Deutsch, RIP; synths forever?)

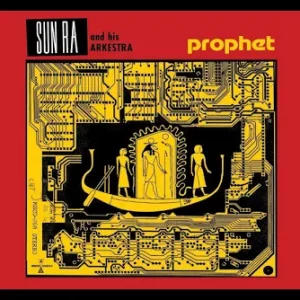

As the year ends/begins, I’m thinking electroacoustic music is a wave of the future. But maybe it’s been superseded by other synth-based genres — synth-pop, EDM, soundtracks a lá Stranger Things. Is Prophet, the just released 1986 weird-sounds bonanza from Sun Ra with his Arkestra exploiting the then new, polyphonic and programmable Prophet-5 synth, timeless […]

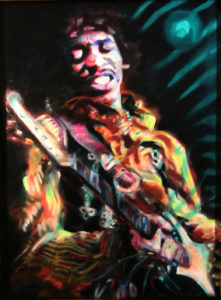

I saw Jimi Hendrix three times

On the 80th anniversary of Jimi Hendrix’s birth (11/27/42), memory and legacy of America’s unsurpassed guitar-artist (written 2011): I’m bouncing around in the back seat of a pal’s car with a couple other high school wannabes, cruising through our leafy-green, cushy but staid Chicago suburb, when the most amazing music comes roaring out of the […]

JazzBash! Immersive virtual Awards event plus!

I daresay the JazzBash! on Sunday, 9/11 is the first ever virtual hybrid Awards party/live Jazz Cruise auction/online concert from six U.S. cities/conference of activist panelists/bar with storytellers and presenters, live improvised painting, exclusive jazz photography exhibits and more — in immersive environments depicting noted jazz sites through which attendees — musicians, critics, the general […]

Who plays the saxophone? And why?

I love the sound of a saxophone, or rather the broad range of sounds available from this family of reeds instruments. Breathy, vocal-like, smooth, light, penetrating, gritty or greasy, able to cry and/or croon (sometimes both at once), it strikes me as capable of the most personal of musical statements, although that’s probably a projection […]

Appreciating Charnett Moffett as a solo bassist

Saddened that bassist Charnett Moffett has died of a heart attack at age 54, I post this appreciation — also serving as a profile — written in 2013 to annotate his solo bass (!) album The Bridge, which he described as “my most personal and challenging release so far.” Solo bass records are rare, and […]