Lest you think I have no sense of fun from my last post, which chastised the Indianapolis Museum of Art for outsourcing its exhibition planning to the public, I thought I would mention an instance where I think engaging the public is fine.

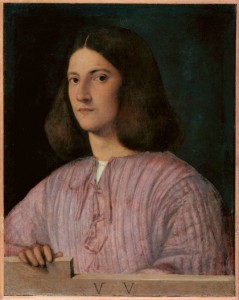

It has been taking place at the Royal Academy since mid-March, in connection with the exhibition, In the Age of Giorgione. The show sounds terrific–you can read this Guardian review of it–and the RA added to it by focusing public attention on a painting that has mystified art historians. Made in the late 1490s,  Portrait of a Young Man has alternately been attributed to Giorgione and to Titian.

It has been taking place at the Royal Academy since mid-March, in connection with the exhibition, In the Age of Giorgione. The show sounds terrific–you can read this Guardian review of it–and the RA added to it by focusing public attention on a painting that has mystified art historians. Made in the late 1490s,  Portrait of a Young Man has alternately been attributed to Giorgione and to Titian.

So the RA is seeking public opinion in a vote–but not after giving three or four sentences of explanation. I do not know what information has been given in the galleries, because I have not seen the show, but online there’s a wealth of it.

Here, for example, Peter Humfrey makes the case for Giorgione. He talks about line, texture, composition, visage of the youth, and so on–with illustrations for comparison. Paul Joannides argues for Titian, citing the composition, the skill of execution, and so on. You don’t have to be an art historian to read either one.

The RA also posted an article from its magazine headlined The Enigma of Giorgione. It posted another magazine feature–two art historians debating whether attribution matters, and another about other artists in Venice at the time.

Now people have a sense of the artist, the times, and the stakes. Now they might cast informed votes.

At the time of this writing, the vote was… I don’t want to say, but only 2% of the participants voted “neither.” You can go to this link to find out (at the bottom).

Either author, it’s a pretty gorgeous picture.

Photo credit: Courtesy of the RA via The Guardian