So much attention is paid to contemporary art in China that I thought it might be a good idea to highlight two exhibitions, on opposite sides of the country, that focus on modern, but historical Chinese art.

Since Oct. 30, the Denver Museum of Art has been showcasing the work of Xu Beihong (1895-1953). His name may not ring a bell, but it should. The Denver museum calls Xu “the father of modern Chinese painting.” Xu, who was one of the first Chinese artists to study in Europe — Paris, in his case — was an advocate for incorporating Western techniques into traditional Chinese painting. Over the course of his career, he became a prominent teacher and global ambassador for Chinese art, making a difference both in China, where he helped revolutionize the arts institutions, and abroad, where he helped reshape international perceptions of Chinese painting.

Since Oct. 30, the Denver Museum of Art has been showcasing the work of Xu Beihong (1895-1953). His name may not ring a bell, but it should. The Denver museum calls Xu “the father of modern Chinese painting.” Xu, who was one of the first Chinese artists to study in Europe — Paris, in his case — was an advocate for incorporating Western techniques into traditional Chinese painting. Over the course of his career, he became a prominent teacher and global ambassador for Chinese art, making a difference both in China, where he helped revolutionize the arts institutions, and abroad, where he helped reshape international perceptions of Chinese painting.

This show will include 61 paintings, most borrowed from the Xu Beihong Memorial Museum, most of which never before been on view in the United States. Read more here about the exhibition and here about the man. The exhibition will end on Jan. 29.

In New York, meanwhile, the China Institute has been displaying Blooming in the Shadows: Unofficial Chinese Art, 1974-1985, since Sept. 15. But as the description notes, few exhibitions have asked the question, how did internationally oriented art appear, given the background of 35 years of socialist realism?

This exhibition does, “focus[ing] on paintings and sculpture from three unofficial groups of artists, the No Names, the Stars, and the Grass Society, which pushed beyond Maoism in the early post-Cultural Revolution era. Each group pursued creatively diverse paths to artistic freedoms under the harsh political strictures and against the accepted aesthetic norms of the time. The work they produced opened the door for the avant-garde movement to emerge in China and paved the way for Chinese artists working today.”

This exhibition does, “focus[ing] on paintings and sculpture from three unofficial groups of artists, the No Names, the Stars, and the Grass Society, which pushed beyond Maoism in the early post-Cultural Revolution era. Each group pursued creatively diverse paths to artistic freedoms under the harsh political strictures and against the accepted aesthetic norms of the time. The work they produced opened the door for the avant-garde movement to emerge in China and paved the way for Chinese artists working today.”

It runs until Dec. 11.

Photo Credits: Six Galloping Horses, Courtesy of the Xu Beihong Memorial Museum (top), and Wang Keping’s Silent, Courtesy of the China Institute (bottom)

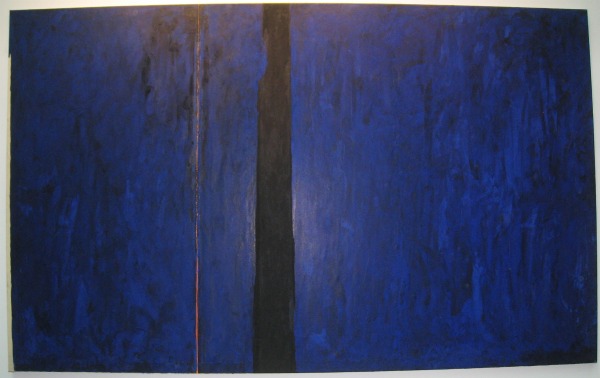

I’m sure many people will visit at first. But it’s an open question whether Still’s art has the staying power, whether there’s enough interest in his works, enough variety in his works, to keep people coming. Last week’s auction,

I’m sure many people will visit at first. But it’s an open question whether Still’s art has the staying power, whether there’s enough interest in his works, enough variety in his works, to keep people coming. Last week’s auction,

All of that is a preface to my praise for what the

All of that is a preface to my praise for what the  And here’s another first, I believe: People who could not get into the opening — which means almost everyone, because this ticket was hotter than tickets to the Super Bowl — were able to watch it at the cinema. That’s right, an art opening — not the Metropolitan Opera — merited live coverage, transmitted to movie theaters. How extraordinary.

And here’s another first, I believe: People who could not get into the opening — which means almost everyone, because this ticket was hotter than tickets to the Super Bowl — were able to watch it at the cinema. That’s right, an art opening — not the Metropolitan Opera — merited live coverage, transmitted to movie theaters. How extraordinary. It’s a show of the Lewis Chessmen, 34 of which have been borrowed from the British Museum for The Game of Kings: Medieval Ivory Chessmen from the Isle of Lewis, which begins on Tuesday and runs through April 22. I took the occasion to write a

It’s a show of the Lewis Chessmen, 34 of which have been borrowed from the British Museum for The Game of Kings: Medieval Ivory Chessmen from the Isle of Lewis, which begins on Tuesday and runs through April 22. I took the occasion to write a  The Met will supplement the Lewis chessmen, which will be shown in an endgame of a famous chess match, with chess pieces from its permanent collection (more details

The Met will supplement the Lewis chessmen, which will be shown in an endgame of a famous chess match, with chess pieces from its permanent collection (more details