The Sotheby’s sale last night brought a total of $315.8 million, which the auction house notes is “the highest for a Contemporary Art Evening sale at Sotheby’s since May 2008 and the Company’s third highest ever, virtually matching the $315,907,000 set at Sotheby’s in November 2007.”

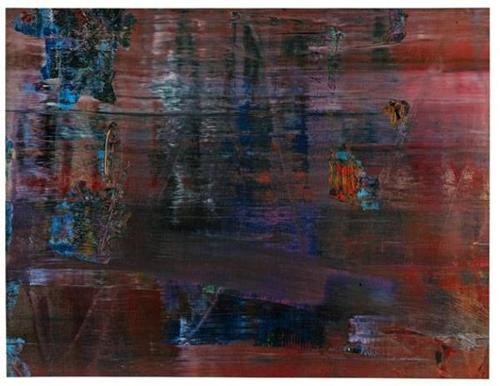

Aside from the Clyfford Still bonanza ($114.1 million, as reported here), Gerard Richter had a great night. His Abstraktes Bild, dated 1997, fetched $20,802,500, with four ardent bidders competing for a painting whose presale estimate was $9 million to $12 million. Further, the collection of eight of his “abstract figuration” works for sale brought a totalof nearly $74.3 million, versus the presale estimate of $27 million to $36.7 million (no estimates include the buyer’s premium).

Aside from the Clyfford Still bonanza ($114.1 million, as reported here), Gerard Richter had a great night. His Abstraktes Bild, dated 1997, fetched $20,802,500, with four ardent bidders competing for a painting whose presale estimate was $9 million to $12 million. Further, the collection of eight of his “abstract figuration” works for sale brought a totalof nearly $74.3 million, versus the presale estimate of $27 million to $36.7 million (no estimates include the buyer’s premium).

The Richter record supplants the one set just last month, which I wrote about here: Kerze (Candle), from 1982, fetched £10,457,250, or just over $16.4 million.

That’s a detail from one of them, from 1992, at left, which sold for $14.1 million.

Credit Richter’s current retrospective at the Tate for some of the fury for Richter. He’s been getting more attention elsewhere lately as well, and I expect it will grow.

For more details on the sale, here’s the Wall Street Journal’s report and here is the New York TImes’s article. And here’s the Richter record-setter:

Other artists with new record prices last night in clude Joan Mitchell, David Hammons, and Dan Flavin.

Other artists with new record prices last night in clude Joan Mitchell, David Hammons, and Dan Flavin.

Walter Pach — art historian, critic, art advisor, champion of modern art, organizer of the landmark 1913 Armory Show — was also an artist.

Walter Pach — art historian, critic, art advisor, champion of modern art, organizer of the landmark 1913 Armory Show — was also an artist.  of Pach, published by Penn State Press. It was written by independent scholar and curator Laurette E. McCarthy, who also curated the exhibition and wrote the accompanying catalogue, The Paintings of Walter Pach.

of Pach, published by Penn State Press. It was written by independent scholar and curator Laurette E. McCarthy, who also curated the exhibition and wrote the accompanying catalogue, The Paintings of Walter Pach. believed that anyone interested in modern art should explore its sources in the paintings of the Italian Renaissance…In 1912 he deliberately simplified his imagery and heightened his color palette, yet these changes were incidental when compared to those that took place in his work after the Armory Show. For approximately five years, Pach embraced the most advanced manifestations of the new art coming out of Europe–especially Fauvism and Cubism–and painted among the most vibrant and daringly experimental pictures of his career, excelling especially in his use of watercolor. After 1920, he reverted to a figurative style…

believed that anyone interested in modern art should explore its sources in the paintings of the Italian Renaissance…In 1912 he deliberately simplified his imagery and heightened his color palette, yet these changes were incidental when compared to those that took place in his work after the Armory Show. For approximately five years, Pach embraced the most advanced manifestations of the new art coming out of Europe–especially Fauvism and Cubism–and painted among the most vibrant and daringly experimental pictures of his career, excelling especially in his use of watercolor. After 1920, he reverted to a figurative style…