No sooner had my review of the exhibition at the Montclair Art Museum titled Matisse and American Art run in The Wall Street Journal on Tuesday than I was off, flying to another exhibition whose review you will see in the next several days, I hope.

No sooner had my review of the exhibition at the Montclair Art Museum titled Matisse and American Art run in The Wall Street Journal on Tuesday than I was off, flying to another exhibition whose review you will see in the next several days, I hope.

But that early morning flight meant that I did not have the chance to post news of my review*Â and, more important, of the exhibition here. The Journal also, as it has recently, created a slide show of ten works in the exhibition.

Here are the nut grafs of my review:

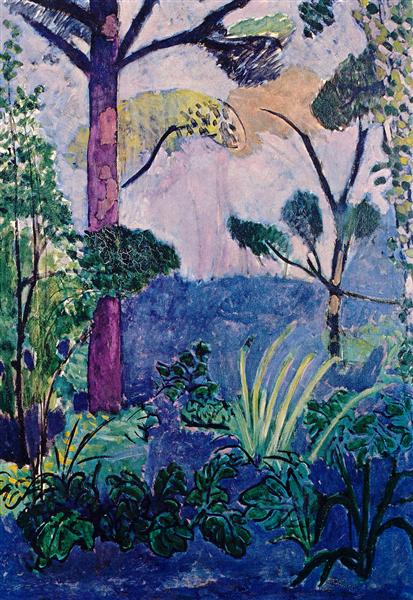

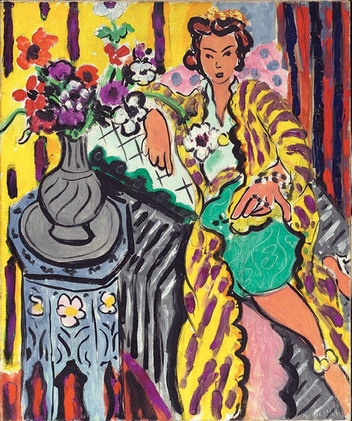

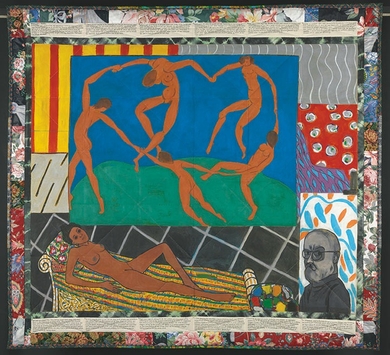

…[In 1908] American artists weren’t laughing either, but for the opposite reason. They were admiring Matisse, studying with him, collecting him and drawing inspiration from him. And they have ever since, as “Matisse and American Art†at the Montclair Art Museum illustrates. With 19 works by Matisse and 44 by others, this enterprising exhibition extends the previously explored territory of Matisse’s influence on postwar painters like Mark Rothko, Helen Frankenthaler and, especially, Richard Diebenkorn backward to early modernist artists like Arthur Dove and forward to contemporary artists like Faith Ringgold.

I don’t have too much to add to my review–if I had had more space, I would have explained some connections. For example, Roy Lichtenstein’s appropriation of a Matisse gold fish bowl in a bronze sculpture works because Lichtenstein used different means–open spaces in the bronze and vertical blocks of yellow and white color–to create the light reflections off the glass bowl that Matisse created in paint.

I don’t have too much to add to my review–if I had had more space, I would have explained some connections. For example, Roy Lichtenstein’s appropriation of a Matisse gold fish bowl in a bronze sculpture works because Lichtenstein used different means–open spaces in the bronze and vertical blocks of yellow and white color–to create the light reflections off the glass bowl that Matisse created in paint.