On Saturday, I took the train to Washington for a look at a couple of exhibitions — one being the retrospective for Danish artist Per Kirkeby at the Phillips Collection. I was not very familiar with his work, but I knew he is considered to be the best (“most highly acclaimed,” the Phillips says in its press release) Scandinavian artist working today.Â

On Saturday, I took the train to Washington for a look at a couple of exhibitions — one being the retrospective for Danish artist Per Kirkeby at the Phillips Collection. I was not very familiar with his work, but I knew he is considered to be the best (“most highly acclaimed,” the Phillips says in its press release) Scandinavian artist working today.Â

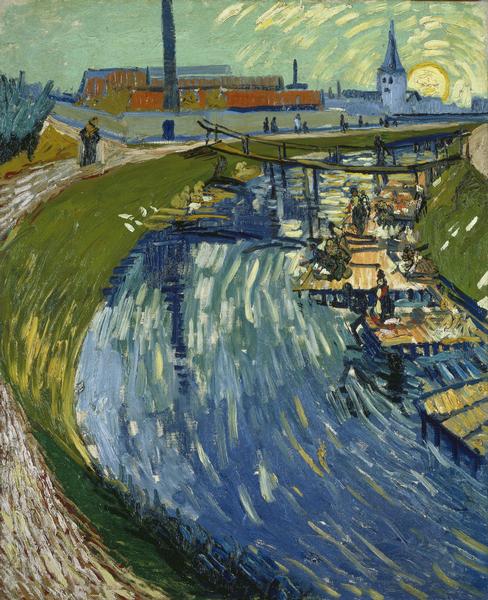

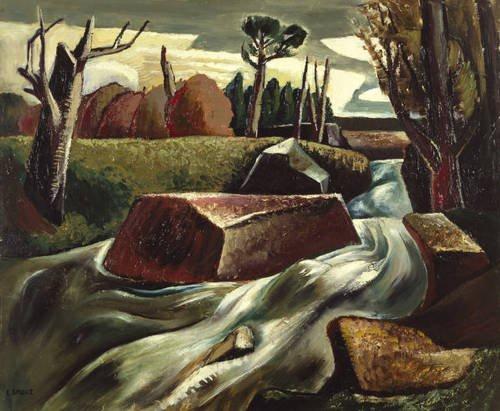

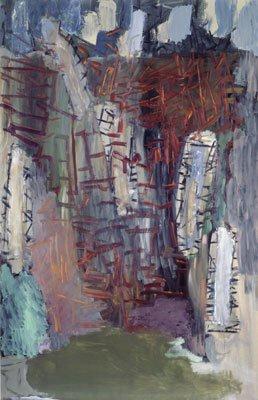

As I walked around the show, I couldn’t figure him out at all. Some paintings were colorful, almost decorative (like New Shadows V, right); others, muddy, indistinct (like Untitled, 1993, left). His bronzes seemed unrelated (not necessarily bad). The selection was very eclectic, and I wasn’t sure how representative these pieces are of his work. They are all said to be about nature, natural history, and sometimes a merger of “the beauty of landscape painting and the grandeur of history painting.”Â

But almost everywhere I saw aspects of other artists better-known in the United States — Guston, Mitchell, Rauschenberg, Richter, Twombly, Salle even — and I tried to figure out from the dates who influenced whom. (One painting, Untitled 2009, which shows horses — a red one, a yellow one — seemed very related to art I’d seen in Iceland in 2011.) When I got home, still thinking about Kirkeby, I thought of the chart that MoMA’s curators and the Columbia University Business School have devised laying out social networks among artists for MoMA’s coming Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925, which will open in late December. (This was called to my attention by a recent article in ARTNews headlined “MoMA Makes A Facebook for Abstractionists.”) Here’s the link to the social network chart (be sure to magnify it, or you’ll strain your eyes), and you can see that Picasso, Kandinsky, Sonia Delaunay and others had the widest networks.Â

Kirkeby, born in 1938, obviously wasn’t on it, but it made me wonder what his network would look like. Â

Kirkeby, born in 1938, obviously wasn’t on it, but it made me wonder what his network would look like. Â

I don’t think I’m the only one a bit mystified by Kirkeby. Notice that this review (which has a very good slide show), in Washingtonian, starts out quoting a British review:Â

In a review of one show at Tate Modern, the London Guardian described his works as “rich, earthy, spearing, dynamic, fiercely inquiring, solemn droll, skeptical, and yet abundantly romantic; perhaps a portrait of the artist as much as his art.â€Â

I got hints as well from an interview with Kirkeby by Dorothy Kosinski, the director of the Phillips, in the catalogue. Such as:

- “There’s this whole idea of being first with some kind of invention or someone being rare and so on. What does it all mean? Artists are there in their own time and they have different reactions, and essentially they are all good. Even the artists we do not like have done their very best, and you have to respect that.”Â

- On a trip to New York, he met George Maciunas, who asked him if he were part of Fluxus. “I don’t want to be a member, because basically I am a painter. I am attached to material and flamboyant things.”Â

- “In the painter community [in Europe], it was not so good to be an intellectual. But I couldn’t change the way I was and still am.”Â

- “It’s far too easy a conclusion, that I paint layer upon layer, therefore I’m a geologist. I wouldn’t emphasize geology too much.”Â

- “In painting, you have to invent, each time, a set of rules. …At a certain point, I know it’s finished and the painting kicks me out.”Â

- “[My wife sometimes] looks in [my studio] and says, ‘that’s beautiful,’ and then this painting is doomed.”Â

- “It’s very easy to be pessimistic about contemporary [art], because it’s all against my idea of art. There is something very didactic about it…”

That’s enough to give you a feel for Kirkeby’s sentiments – you’ll have to read the catalogue (too bad that an excerpt of the interview isn’t online). Some of you may find him to be pretentious, but I didn’t. I not entirely convinced by his art, but having read parts of the catalogue I think he’s thought-provoking. Which is what an artist is supposed to be, right?

Good for the Phillips for introducing many of us to this artist.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the Phillips Collection