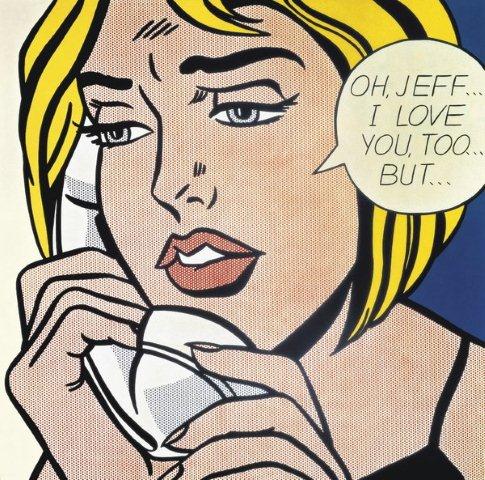

In addition to going to the Per Kirkeby exhibit at the Phillips Collection on my trip to Washington a week ago Saturday, I also stopped in to see several shows at the National Gallery. The Roy Lichtenstein retrospective, officially opened last Sunday, was available to families and members that day — in preview – and I was kindly allowed in, too. I wasn’t going to write about it, though, because — frankly — while I am no expert on him, I have only slight appreciation for the artist, and this show didn’t raise the level. I find his work, in total, to be shallow and at times even hollow — even though I think some of the paintings are pleasing to look at (especially his late works, Landscapes in the Chinese Style).

Then I read Holland Cotter’s review in Friday’s New York Times, and it made me think about Nicholas Penny’s comments on contemporary art posted here last week, particularly the line about a “lamentable lack of critical debate about contemporary art.”

Then I read Holland Cotter’s review in Friday’s New York Times, and it made me think about Nicholas Penny’s comments on contemporary art posted here last week, particularly the line about a “lamentable lack of critical debate about contemporary art.”

Cotter didn’t pan Lichtenstein, but readers should notice that he employed several words and phrases that betray at least a mildly negative view: “virtually foolproof art style,” “narrow in range,” “ergonomically comfortable to the eye,” “clever, if slight,” “diverse but unrevealing,” etc. The headline went a step further: “Cool. Commercial. Unmistakable.”

Cotter’s ending:

Lichtenstein changed art to some extent, but nothing else. …his work looks like no one else’s, and some of it still feels fresh and audacious. He encapsulates, at least in his early work, the spirit of an era. He is embedded in the culture now, and unlikely to be dislodged.

Let’s call him an American classic, and leave it at that.

Damning with faint praise? It made me wonder whether anyone else even began to challenge the ordothoxy (a Lichtenstein painted fetched more than $43 million at auction recently, so vested interests are operating here). I looked up other reviews of the exhibit.

In the Washington Post, Anne Midgette, sounded a positive note:

…what animates [his work] is not solely its inherent social criticism, but the tension between the individuality of the painter’s hand and eye and the impersonality of what he uses them to illustrate. This tension runs through the whole show, and is what made it such a delight, even a revelation. …After [his]1993 retrospective, I came away feeling Lichtenstein had had a burst of fecundity in the 1960s and ended up repeating himself or looking in vain for a way to get back to that initial energy. The current show, by contrast, shows him dumping a huge bag of tricks out on the table in the ’60s and continuing to play with them, examine them, and follow them ever further to new solutions, for the rest of his life.

And in the Chicago Tribune, which published a review last May when the exhibit was on view at the Art Institute of Chicago, Lori Waxman gushed:

[His appropriation of comic images and use of Ben-Day dots in Look, Mickey]Â was a great gambit, one of the finest of the 20th century, a period of art-making full of one gambit after another….By the mid-’60s he’d turned to landscape as a subject matter, depicting sunrises, seascapes and cloudy skies as amalgamations of colored dots, solid lines and blank spaces. The results, on view in a somewhat overhung gallery, are breathtaking. They’re also stunning in their efficiency and abstraction: Lichtenstein borrowed these images from comic books, keeping the background and leaving out all the extraneous details. The ensuing gorgeousness can be hard to believe.

I am sure that all three critics quoted here were sincere in their appraisals, and after all, their views are supposed to be subjective. But I think it’s time to have more debate about Lichtenstein. Of course, Peter Schjeldahl hasn’t yet weighed in, nor has Jed Perl. Maybe they will stir the pot.

This show travels next to the Tate Modern. It’s, no question, a crowd-pleaser: in Chicago, it was the Art Institute’s best-attended exhibition in ten years, drawing about 350,000 people.

And here’s the appropriate kicker: “The retail business was ’31/2 times what we projected,’ †a spokeswoman told the Tribune.