I enjoyed seeing the Brooklyn Museum’s Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, but as regular readers of this blog know, it’s always all about the art for me. And while there were plenty of excellent photographs, costumes and MesoAmerican artifact on view there, the exhibit was about Frida–not about her art. To be sure, that’s what the exhibit was about her, not about her art, and it succeeded at its goal.

But as I wrote in the concluding paragraph of my review, which appears in today’s Wall Street Journal, “This engaging and sometimes engrossing exhibition will delight Kahlo fans, but for me it’s a missed opportunity to dilute the fixation on her biography and engage them with more of her path-blazing, idiosyncratic art. The balance between her life and her art is, as ever, askew.”

So what is in the show? The photographs of Kahlo create the narrative of the exhibition, and they range from family photos to works of art by the likes of Tina Modotti, Edward Weston and Lola Ãlvarez Bravo. There’s Frida’s jewelry, shawls, bags, costumes. There’s a cabinet full of objects from Brooklyn’s permanent collection.

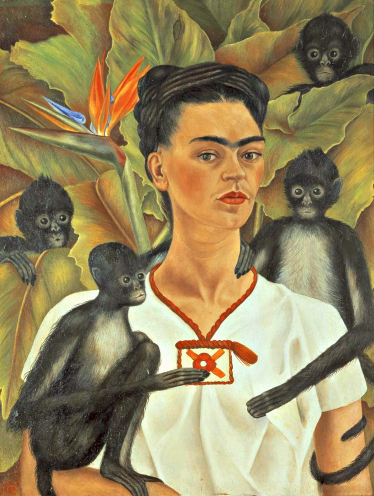

There are a few fine paintings here by Kahlo, which I mention in my review. I wish there had been more and better.

Oddly to my eyes the very best painting in this exhibition is by an unknown artist. Portrait of Dona Maria de los Angeles de Cervantes Ozta y de Velasco was painted in Mexico around 1935 and purchased by the museum in 1952. It’s so unheralded that the BM website shows only a black-and-white picture of it. (I took the photo posted here, from an angle only because the lighting obscured a frontal photo.)

It has this label: “Doña Maria in three-quarter length and view facing to the left side of the picture in which she is seated. Her black hair is parted in the center and she has curls at either side under her ears with some flowers in her hair over her left ear. Her black velvet dress is off-the-shoulder and edged with white lace like the sleeves which come to the elbow. The bodice is pointed and the skirt gathered. She wears white gloves and there is a heavy gold chain ornament around her neck.â€

It is in the exhibit because that gold ornament is identical to one worn by Kahlo in a nearby photo.

Kahlo had a big exhibition of her work in Philadelphia in 2008. Maybe that was on Brooklyn’s mind when it took this exhibit. Or maybe Kahlo is just to big a draw to turn away any legitimate show.