Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World is notable for several reasons. But the one I want to dwell a little on here is a point I made in the final paragraph of my review of this show at the Getty Museum for The Wall Street Journal, which was published in Monday’s paper.

Here’s what I wrote: “Book of Beasts demonstrates well how an esoteric subject can appeal to the general public without stooping to conquer, without losing its scholarly approach. It shows the bestiary to be a wondrous thing.”

We’ve all seen museums do a lot of odd things in recent years in attempts to draw people into their galleries–cat video contests, show-your-own-art alongside masterpieces, crowdsourcing curatorial decisions, mixing up unrelated art, and so on. Some may have “worked,” in the sense that they did attract visitors–but generally only for the one exhibit or particular gesture of outreach.

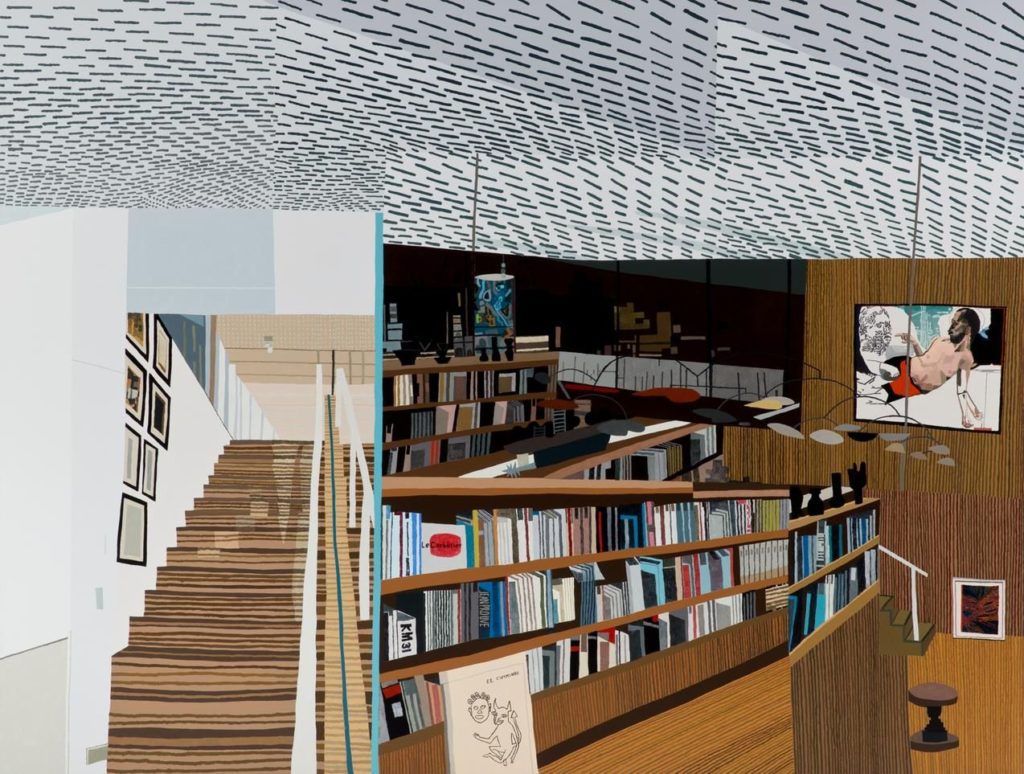

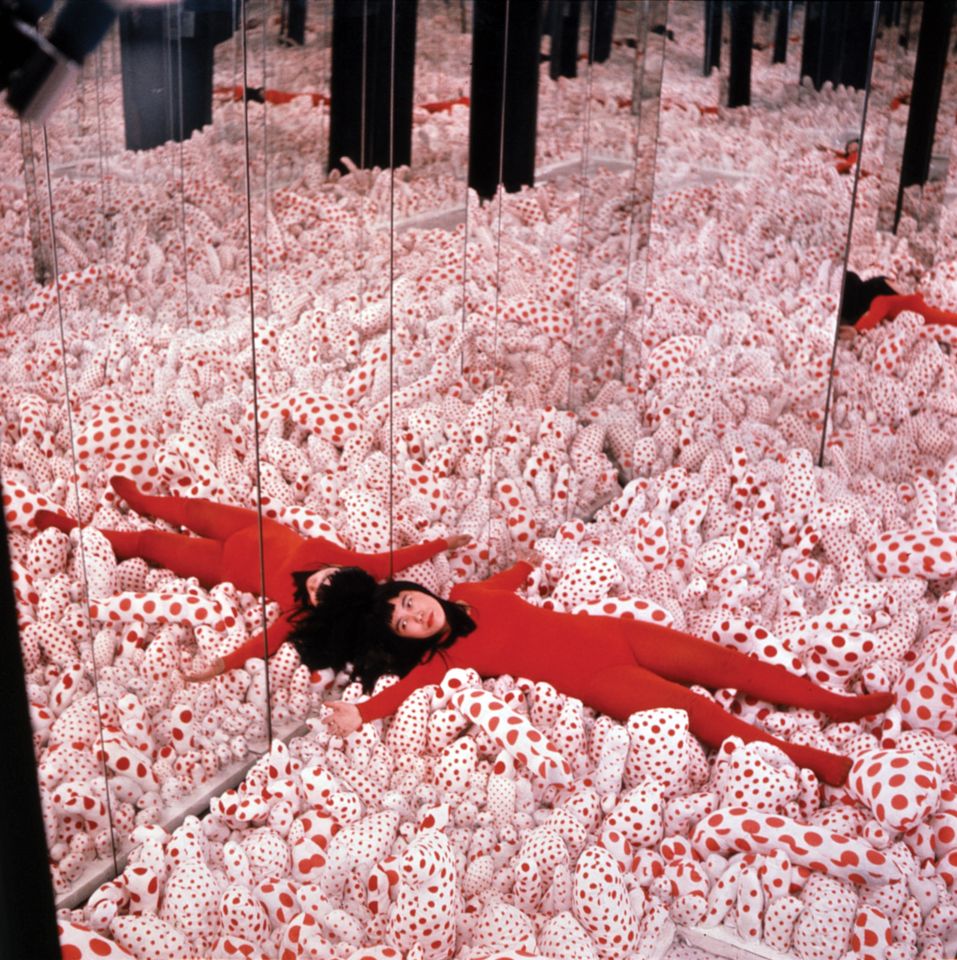

Instead, the Getty, with Book of Beasts, generally took the high road. No dumbing down, no “unicorn days,” no silly contests. The museum has scheduled a talk linking the show to Harry Potter–but at least is is a lecture. It also added, in the final gallery of this exhibition, several contemporary art pieces–but not only were they well-chosen, but also the Getty marked them off by painting the walls in that gallery white, unlike the colored walls of the rest of the exhibit. That helped set a different tone.

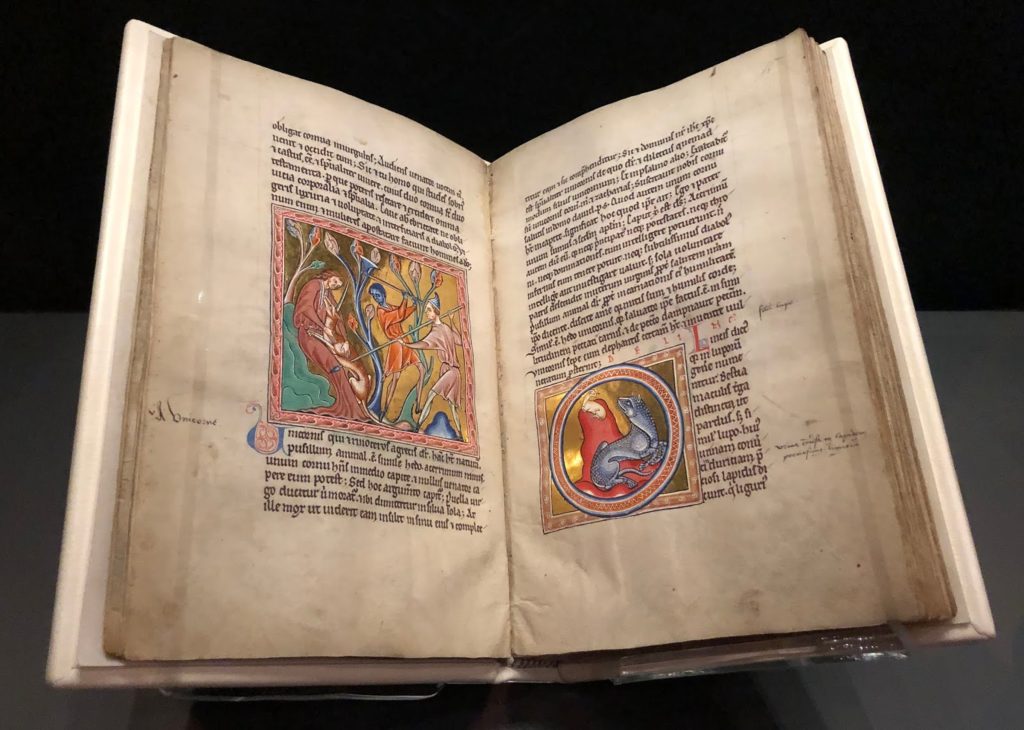

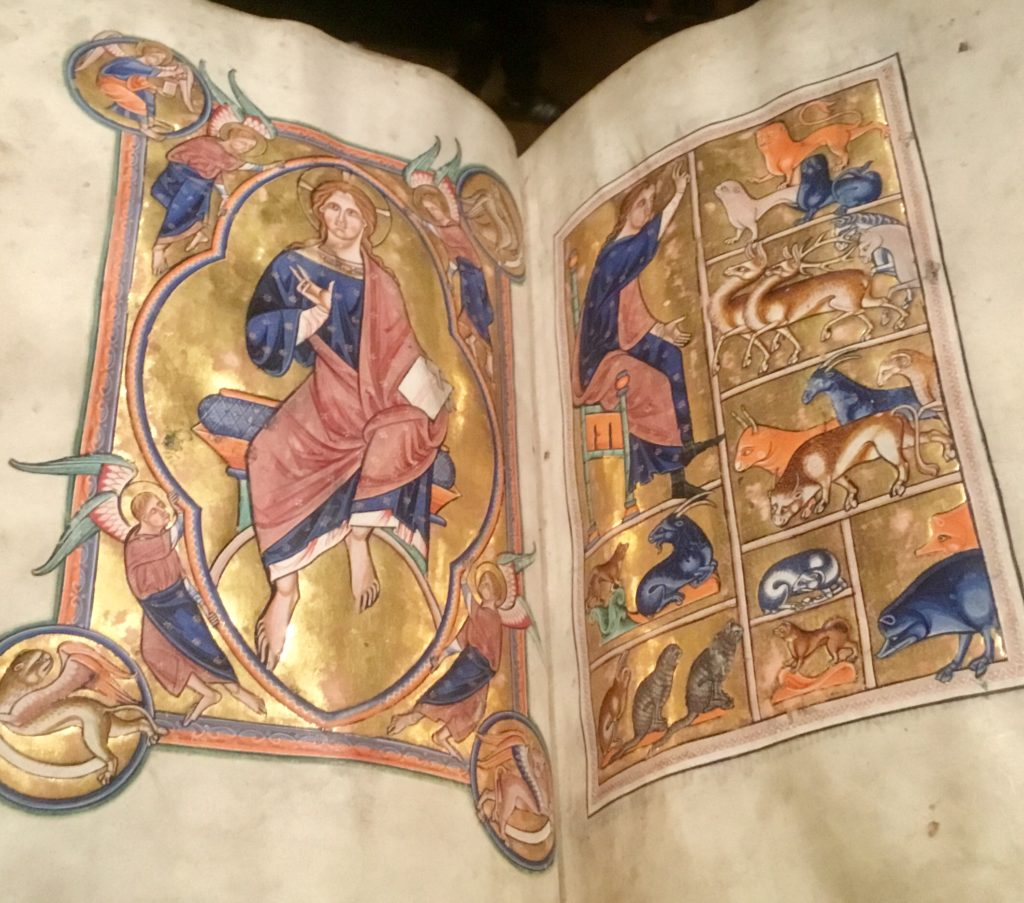

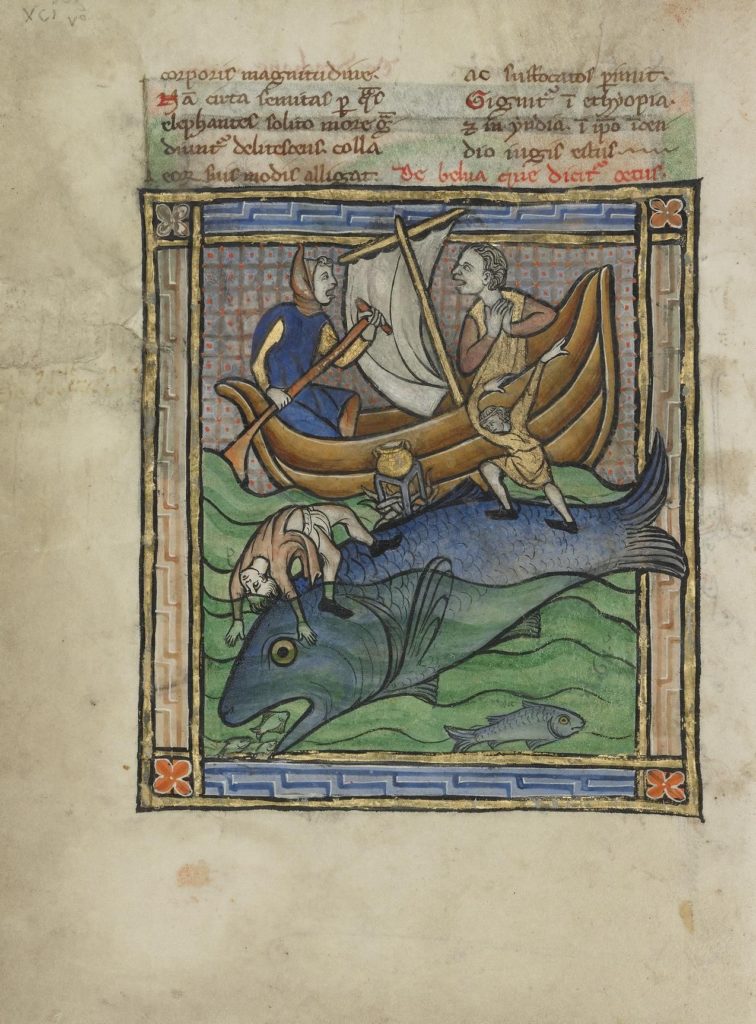

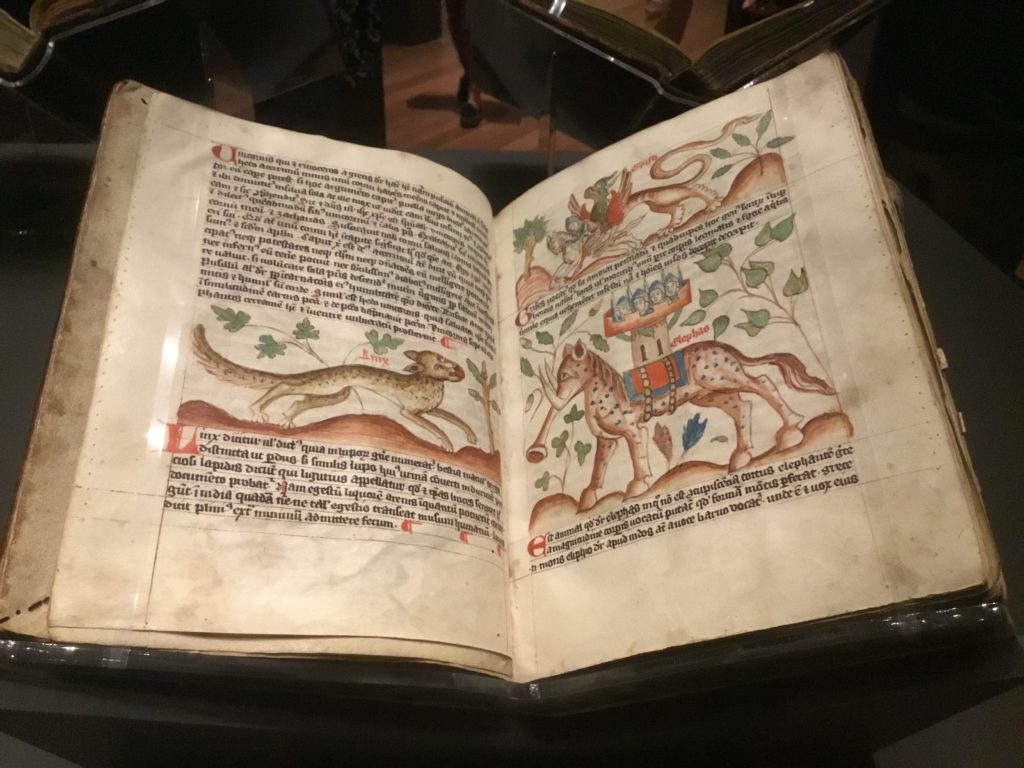

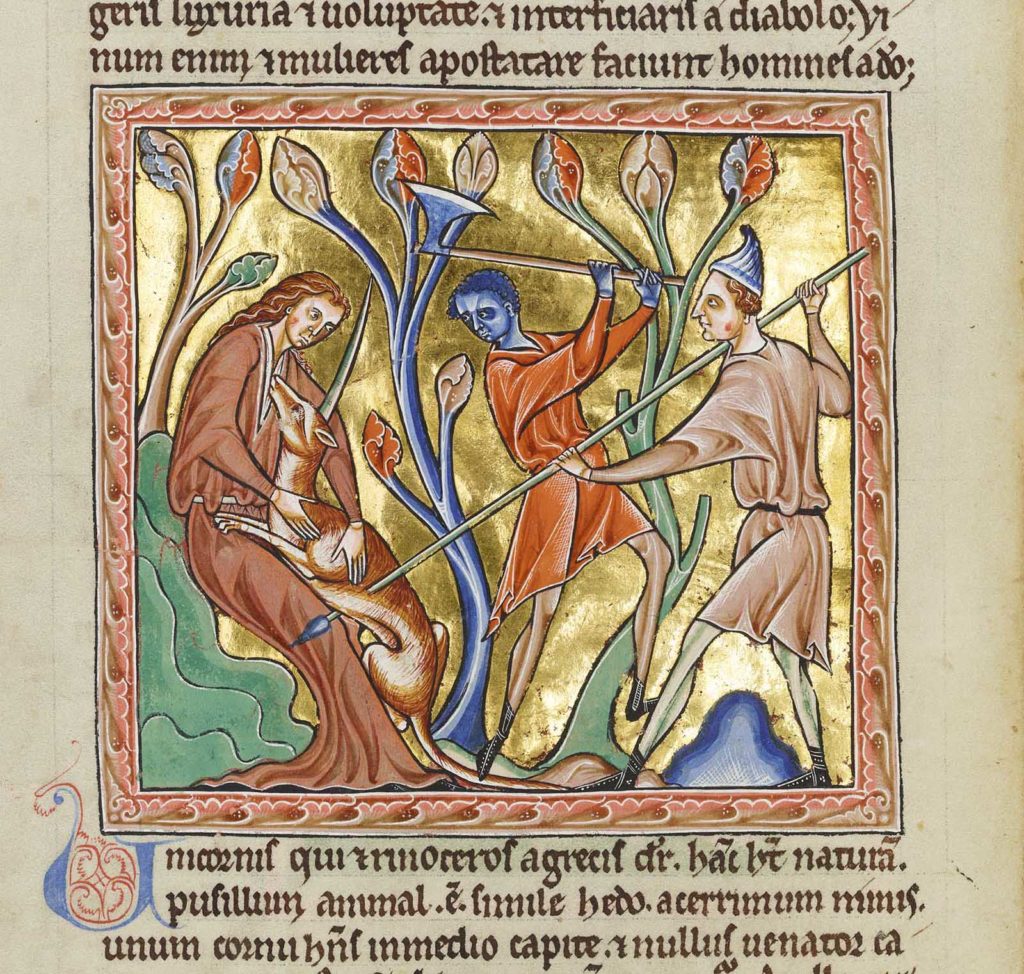

What did the Getty do right, then? For this first major museum exhibition on bestiaries, it assembled a third of the world’s surviving Latin illuminated bestiaries, plus others in other languages, and borrowed tapestries, ivories, objects, other manuscripts, paintings, even medieval ceiling fragments, to illustrate theses books’ influence. It gave them a beautiful display despite the low lighting needed to preserve the manuscripts. It built listening stations through the exhibit that explain the signifcance of certain animals, including fantastical ones like the bonnacon and the griffin. It published a beautiful and enlightening catalogue. Etc.

Ok, you say, but it is the Getty, which has lots of money, To which I say, those overtures created by other museums to bring in people cost money too.

If you have a chance to visit the Getty for this exhibition, I think you’ll agree with my verdict. In another passage in my review, I wrote:

“Bestiaries were like animal encyclopedias, but with a higher purpose: Created by inventive artists and scribes, they were intended to enkindle in readers awe for the natural world and to impart religious stories and moral allegories.”

The Getty show seems to me to have striven to create awe for bestiaries–and it succeeded. I’ve posted a few samples–and there is more online at the Getty website.