A lot of people today are interested in “design.” Unless they are furnishing a home, not all that many are interested in “decorative arts.” They are, of course, fraternal if not identical twins. Yet decorative arts galleries at many museums seem empty, while design exhibitions are crowded.

So today’s announcement is welcome news:

So today’s announcement is welcome news:

The Brooklyn Museum and Bard Graduate Center announced today a collaborative, multiphase project aimed at rethinking the presentation and study of American decorative arts. Starting in fall 2017, Bard Graduate Center faculty and students and Brooklyn Museum curators will come together as a think tank to examine the organization, display, and interpretation of the Brooklyn Museum’s extensive collection of American decorative arts. This will launch a series of courses on American decorative arts at the Brooklyn Museum…

That and more work will take place and then:

The project will culminate in a full-scale exhibition, curated in part by students, at the Brooklyn Museum on the work of Brooklyn craftspeople, makers, artisans, and artists, and their place in the history of decorative arts and design.

The Brooklyn Museum has a splendid decorative arts collection, with objects dating to the 17th Century, and a wealth of period rooms dating from 1725 to 1929. They are not visited enough. Brooklyn has in the past tried interventions–I recall in particular how Yinka Shonibare made site-specific works for the period rooms during his 2009 exhibition there. That worked, as I recall, but it has been a long time.

The Brooklyn Museum has a splendid decorative arts collection, with objects dating to the 17th Century, and a wealth of period rooms dating from 1725 to 1929. They are not visited enough. Brooklyn has in the past tried interventions–I recall in particular how Yinka Shonibare made site-specific works for the period rooms during his 2009 exhibition there. That worked, as I recall, but it has been a long time.

It will be fascinating to see how graduate students grapple with this issue; I hope it will be in a respectful way.

Photo Credits: Two period rooms at the Brooklyn, courtesy of the museum.

*I consult to a foundation that supports the Brooklyn Museum.

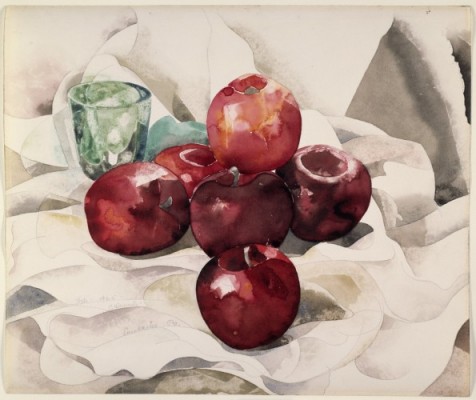

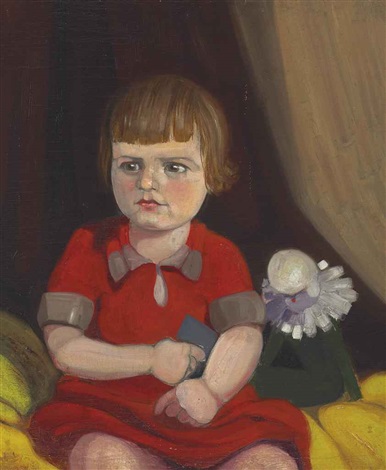

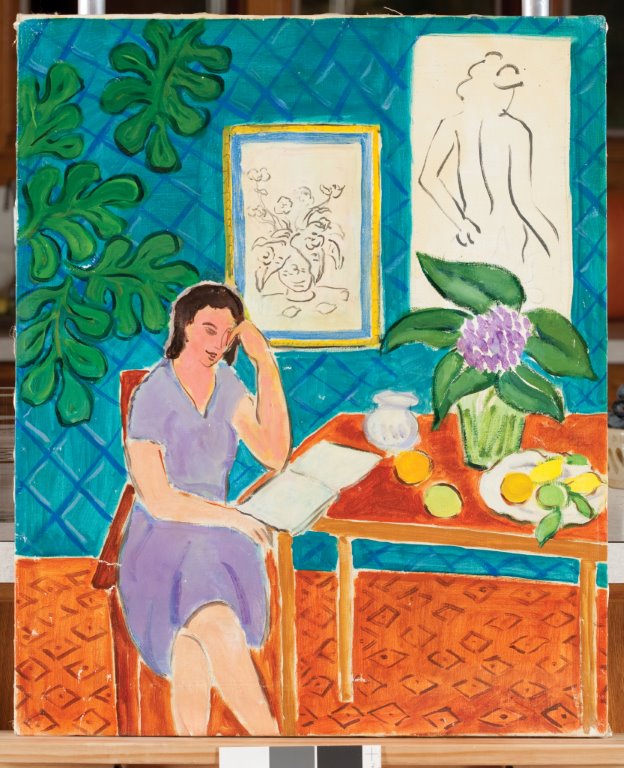

American Watercolor In the Age of Homer and Sargent, now on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is an exhausting exhibition, in a good way. It displays more than 170 artworks and covers the period from the 1860s to 1925. It is,

American Watercolor In the Age of Homer and Sargent, now on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is an exhausting exhibition, in a good way. It displays more than 170 artworks and covers the period from the 1860s to 1925. It is,  And yet this excellent exhibition–I can’t say enough about how good it is–gives us just one small gallery of works from that high point. One Burchfield, one Hopper, one Marin, two Demuths–no Doves. Two O’Keeffes on the same subject.

And yet this excellent exhibition–I can’t say enough about how good it is–gives us just one small gallery of works from that high point. One Burchfield, one Hopper, one Marin, two Demuths–no Doves. Two O’Keeffes on the same subject.