I’ve been out to the Getty twice in recent months, both times to see (and review) interesting, ambitious exhibitions–one piece, about Eyewitness Views: Making History in Eighteenth-Century Europe, will be in tomorrow’s Wall Street Journal (and is online, in its slightly longer version, now), and the other, for Shimmer of Gold: Giovanni di Paolo in Renaissance Siena, ran last October.

And of course, I’ve been watching from afar as the museum presents exhibitions, makes acquisitions and plans programs. Without jinxing it, I hope, I’m glad to say that the Getty Trust’s messy structure, which has often caused problems in the past, particularly between the Trust’s president and the museum’s director, seems to be working well now.

I was among the skeptics several years ago. When James Wood, the president, died unexpectedly, not long after troubles erupted between and the then-museum director Michael Brand, who left, I felt the Trust’s structure needed to change. It had frequently been a source of friction–generally between those two officials–and possibly the cause of its under-performance over the years. Somehow, the research, conservation and foundation heads got along with the Trust’s president, and it should have been okay for the museum director, too–in theory–but somehow it never had been. I therefore thought the trustees might take the opportunity to restructure.

I did, however, say, when Timothy Potts was appointed as museum director–following the appointment of James Cuno as Trust president, that

I did, however, say, when Timothy Potts was appointed as museum director–following the appointment of James Cuno as Trust president, that

…whether it works or not has always depended on the personalities involved. It remains to be seen whether the five people now in place, James Cuno at the trust, and the heads of four divisions will work together nicely.

Enough years have passed–Potts took the job in 2012–to make an assessment. So, I say now, maybe the structure is fine–the errors in the past really were mostly about personality. I hope I haven’t missed signs of turmoil.

But back to Eyewitness Views–a show of view paintings that chronicle events, festivals, ceremonies, etc. in history. They served to record the commissioner’s view of that history for contemporaries and for generations that came later.

The exhibit includes pictures you’ve probably never seen before, at least not on these shores. Certainly, not every one is a masterpiece–but they are, the exhibition argues–the best of the vedute paintings because they were (in my words) “bids by the painters to vault themselves into the ranks of history painters, who occupied the highest rung of the art historical hierarchy” at the time. Their other view pictures, which lacked the historical content of these works, were disdained as souvenirs by the academy.

Interestingly, to me, you and I have probably walked past these paintings at museums and on to other, nearby works that seem more interesting. But at the Getty show they somehow become more visible, more interesting, surrounded by like works.

Interestingly, to me, you and I have probably walked past these paintings at museums and on to other, nearby works that seem more interesting. But at the Getty show they somehow become more visible, more interesting, surrounded by like works.

Even if you can’t go, the Getty–like an increasing number of museums these days–is making it easier for people to get a glimpse of what they are missing. If you go to this link, you will see parts of the exhibition and its themes. Go to this link, and you can hear the audio guide. I rarely take the audio guide, but I did listen to this one once I returned home to New York, because the curator, Peter Bjorn Kerber, had told me that the Getty had used real archival descriptions of the events in some of the paintings, read by actors, in the guide. Very interesting. And not too long.

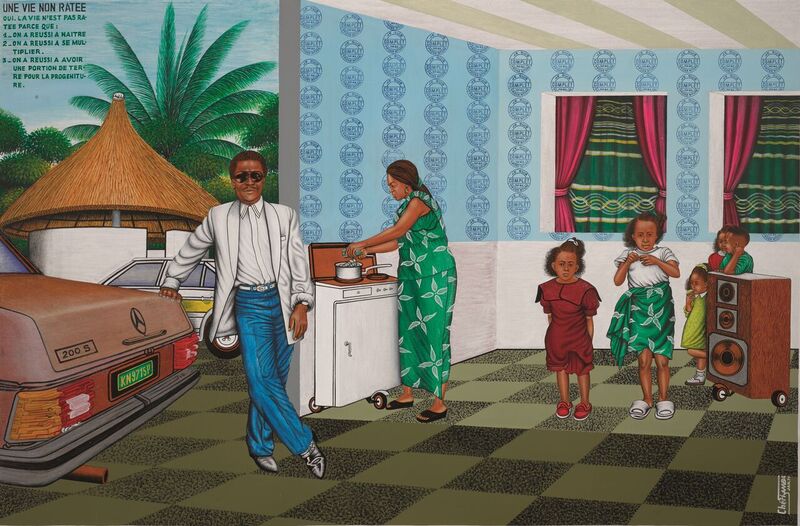

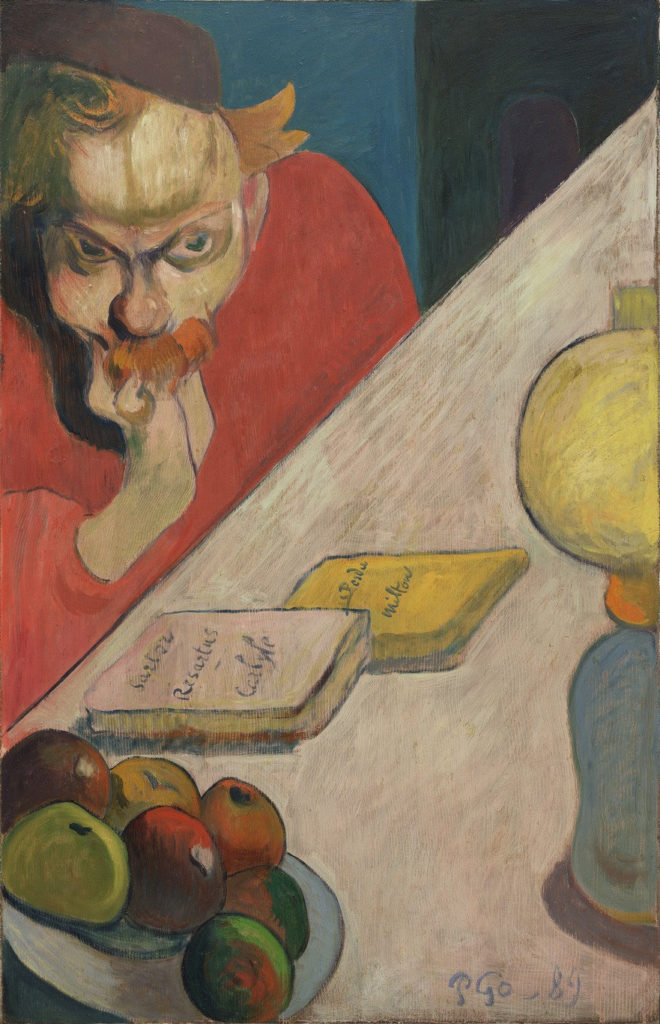

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the Getty, top to bottom:Â