The Denver Art Museum may kill me for doing this — I didn’t ask permission or tell them in advance — but I want to share with you some of the Learning Moments (I think that’s what they are calling them) the museum’s staff has developed for Becoming van Gogh, the exhibition I wrote about yesterday. I couldn’t fit them into my article. But like the wall about terracotta at the Met’s current Bernini exhibition, I think they are models of what museum-goers should be able to see. And I’d like to see them posted online as well — so people can go back to them.

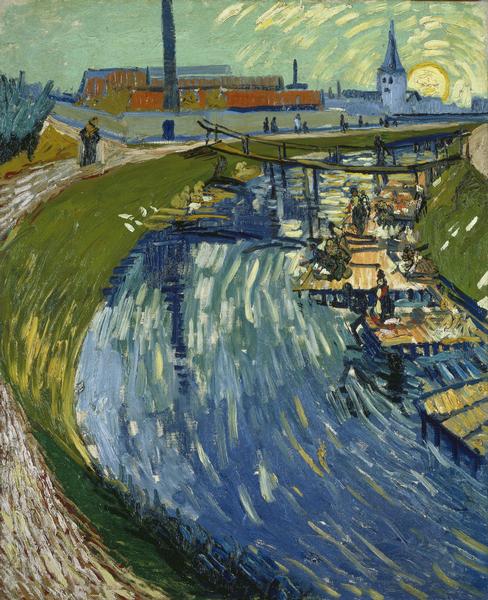

The Denver exhibit is, remember, a scholarly show — it explains how van Gogh became van Gogh.

The Denver exhibit is, remember, a scholarly show — it explains how van Gogh became van Gogh.

One of the large panels talks about Charles Bargue’s Drawing Course, “a three volume do-it-yourself manual with an emphasis on drawing the human figure. Van Gogh got hold of the set and within six months he diligently copied all 197 plates at least once and all sixty of the nude poses at least three times.”

Later, we learn in the same panel that only two of his Bargue drawings survive — because van Gogh’s mother threw the rest away! What child or parent isn’t going to relate to that?

Timothy J. Standring, the curator, could not borrow either of the two surviving drawings, but he was able to find a copy of the Barque book — at Oberlin College, which agreed to lend it to the exhibition.

A second panel is about color. Van Gogh said “A good understanding of [color] is worth more than seventy different shades of paint.” He wrote to his brother, Theo, explaining his ideas about color and saying he was preoccupied by color. The panel goes on:

Somehow Van Gogh hit upon a way to experiment with color by winding different colors of yarn together. This astonishingly simple, cheap, and yet effective method kept the colors separate, just as Van Gogh kept his colors separate on the canvas in short, side-by-side brushstrokes of unmixed paint.

Van Gogh’s original balls of yarn are in the collection of the van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

A third panel is about the perspective frame he built for himself, which he used throughout his career.

And a fourth is about his episodes at a drawing class that used plaster casts, which he hated. But why are his figure drawings from these classes of a woman’s backside? “Van Gogh and his new friend, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, were assigned seats typically reserved for the weaker students: looking at the sculpture’s backside.”

These tidbits qualify as what some editors refer to as “cocktail party conversation” — which is to say that they are memorable, fodder for casual conversation, buzzy — yet they are enlightening about van Gogh. Even if you knew about these facts before, they’re worth being reminded about.

When I started this post, I intended to upload the panels for you to view. But, it turns out, they are too big for this website.

You will just have to visit the Denver show yourself. Or get the catalogue.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum (Canal with Women Washing)