Hurricane Sandy has, as my last brief post indicated, messed up a lot of lives and livelihoods in the art world, among others. Late today, Sotheby’s postponed its Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale, moving it from Monday, Nov. 5, to Thursday, Nov. 8. Christie’s sale had been set for Wednesday, the 7th, and it seems to be going ahead.

Earlier this week, the International Fine Print Dealers Association postponed the annual opening of its print fair here in New York from tonight until tomorrow, and the International Print Center moved the opening of its annual fall print exhibition from last night to tonight and then was forced to postpone until further notice. IPC is based in waterlogged Chelsea, which has little if any electricity.

Earlier this week, the International Fine Print Dealers Association postponed the annual opening of its print fair here in New York from tonight until tomorrow, and the International Print Center moved the opening of its annual fall print exhibition from last night to tonight and then was forced to postpone until further notice. IPC is based in waterlogged Chelsea, which has little if any electricity.

But I am going ahead with what I planned to blog about anyway — as I had two connections to print week. For a start, I wrote a piece about the print market for the October issue of Art + Auction. It has not been posted on line, though it’s on my website. Here’s the money quote, so to speak:

Traditionally, fine prints have appealed to new art buyers with limited resources as well as to committed collectors who are pursuing the gamut of works made by favored artists. But in recent years, with the very best paintings fetching record-breaking prices that place them beyond the reach of all but the top 0.1 percent of buyers, prints have been getting a second look from a broader range of people. Collectors are learning that prints may be the best way to purchase distinctive images by well-known artists, and that many artists devote considerable effort to making important, highly desirable works in print mediums. Moreover, in the world of online art sales, prints have been a success story.

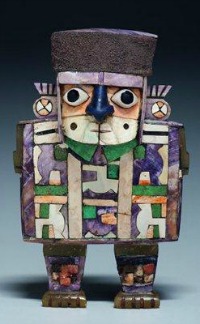

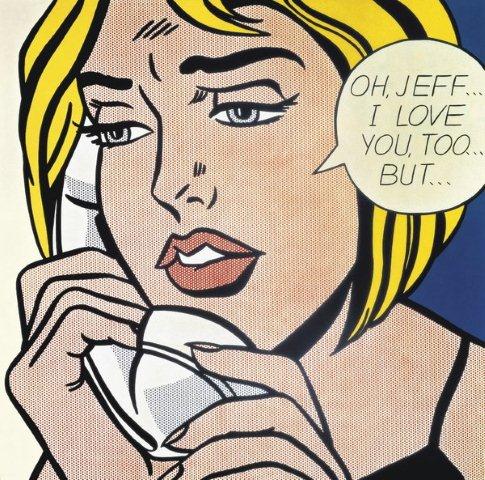

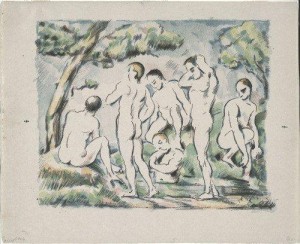

Read further and you’ll find out where you can buy a Cezanne for $35,000, among other samplings. The best thing about writing that story was reminding myself, and readers, that prints aren’t copies of other works — artists use them for many reasons, including to test out techniques and images, and they’re originals.

Which is a nice segue to my second connection: in August, I served on the jury for the New Prints show at the IPC, and I wrote the essay for the exhibition. It will be published online once the show opens, and I will link to it here. It isn’t easy for six people to review some 2,600 prints together in one day (we could preview them online) and then agree on the “best.” We were tough — we chose only 36 prints by 26 artists.

Which is a nice segue to my second connection: in August, I served on the jury for the New Prints show at the IPC, and I wrote the essay for the exhibition. It will be published online once the show opens, and I will link to it here. It isn’t easy for six people to review some 2,600 prints together in one day (we could preview them online) and then agree on the “best.” We were tough — we chose only 36 prints by 26 artists.

After reviewing the process in my mind, and explaining in print what we didn’t do (seek balance, etc.), I was forced to distill what we did this way:

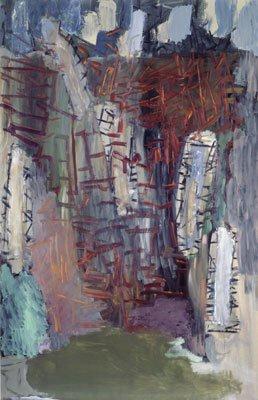

If pressed to describe how we made our decisions, I’d say that a print had to strike us viscerally. It had to have visual impact. And it had to speak to us, sometimes directly, sometimes – we discovered afterwards, when we reviewed our selections – in relation to another print. It had to have staying power, lingering in our minds. Nothing slipped in – that’s why the final count is so small…

We chose prints that were funny, beautiful, romantic, shocking, delicate, brutal, inventive, emotional, confronting, confining, expansive, and lyrical….

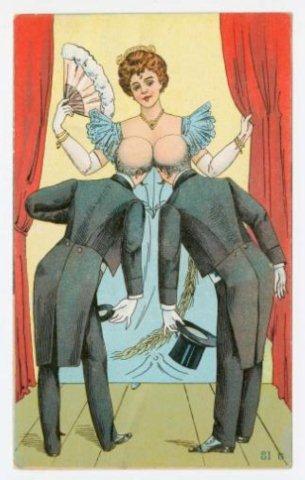

I’ll give you a few more hints: some were aesthetically pleasing, of course, but others had a built-in conflict, a look but don’t look aspect, perhaps, or a beauty-and-discomfort angle.

All of this has given me a new appreciation for prints, and I’ll be going tomorrow to the delayed opening of the fair.

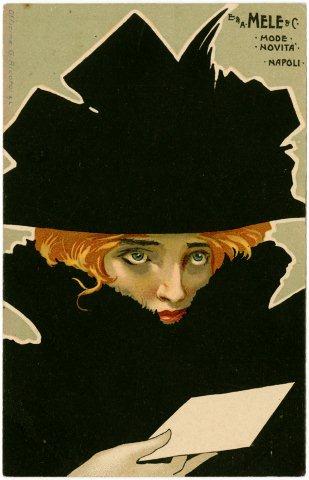

Photo Credits: Courtesy of Pace Master Prints (top); Galerie St. Etienne (bottom)